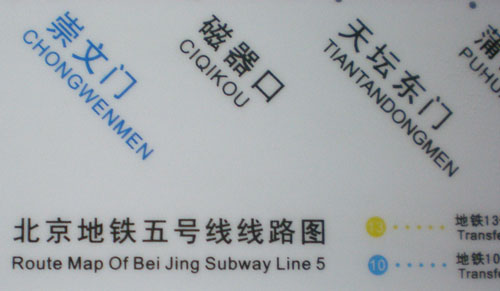

Until very recently, Google Maps gave street names in Taiwan in Tongyong Pinyin — most of the time, at least. This was the case even for Taipei, which most definitely has long used Hanyu Pinyin, not Tongyong Pinyin. The romanization on Google Maps was really a hodgepodge in the maps of Taiwan. And it’s still kind of a mess; but now it’s at least more consistent — and more consistent in Hanyu Pinyin.

First the good. In Google Maps:

- Hanyu Pinyin, not Tongyong Pinyin, is now used for street names throughout Taiwan

- Tone marks are indicated. (Previous maps with Tongyong did not indicate tones.)

Now the bad, and unfortunately there’s a lot of it and it’s very bad indeed:

- The Hanyu Pinyin is given as Bro Ken Syl La Bles. (Terrible! Also, this is a new style for Google Maps. Street names in Tongyong were styled properly: e.g., Minsheng, not Min Sheng.)

- The names of MRT stations remain incorrectly presented. For example, what is referred to in all MRT stations and on all MRT maps as “NTU Hospital” is instead referred to in broken Pinyin as “Tái Dà Yī Yuàn” (in proper Pinyin this would be Tái-Dà Yīyuàn); and “Xindian City Hall” (or “Office” — bleah) is marked as Xīn Diàn Shì Gōng Suǒ (in proper Pinyin: “Xīndiàn Shìgōngsuǒ” or perhaps “Xīndiàn Shì Gōngsuǒ“). Most but not all MRT stations were already this incorrect way (in Hanyu Pinyin rather than Tongyong) in Google Maps.

- Errors in romanization point to sloppy conversions. For example, an MRT station in Banqiao is labeled Xīn Bù rather than as Xīnpǔ. (埔 is one of those many Chinese characters with multiple Mandarin pronunciations.)

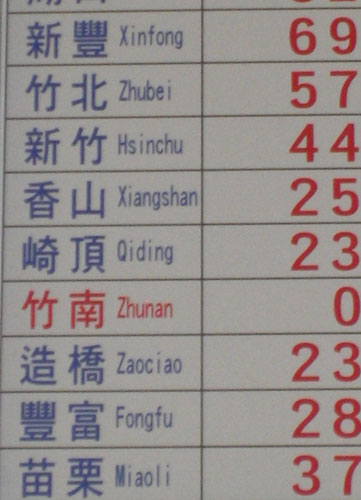

- Tongyong Pinyin is still used in the names of most cities and townships (e.g., Banciao, not Banqiao).

Screenshot from earlier this evening, showing that Tongyong Pinyin is still being used in Google Maps for some city and district names (e.g., Gueishan, Sinjhuang, Banciao, Jhonghe, Sindian, and Jhongjheng rather than Hanyu Pinyin’s Guishan, Xinzhuang, Banqiao, Zhonghe, Xindian, and Zhongzheng, respectively).

I don’t have any old screenshots of my own available at the moment, so for now I’ll refer you to an image that Fili used in an old post of his. Compare that with this screenshot I took a few minutes ago from Google Maps of the same section of Tainan:

Note especially how the name of the junior high school is presented.

- Previously “Jian Xing Junior High School”.

- Now “Jiàn Xìng Jr High School”.

This is typical of how in old maps some things were labeled (poorly) in Hanyu Pinyin. (Words, not bro ken syl la bles, are the basis for Pinyin orthography. This is a big deal, not a minor error.) And now such places are still labeled poorly in Hanyu Pinyin, but with the addition of tone marks.

I’d like to return to the point earlier on sloppy conversions. Surprisingly, 成都路 is given as “Chéng Doū Road” rather than as “Chéngdū Road“.

![screenshot from Google Maps of 'Cheng Dou [sic] Rd', near Taipei's Ximending](https://pinyin.info/news/news_photos/2009/11/cheng_dou_road.gif)

Although “Xinpu” might not be the sort of name to be contained in some romanization databases, there is nothing in the least obscure about Chengdu, the name of a city of some 11 million people. Google Translate certainly knows the right thing to do with 成都路:

But Google Maps doesn’t get this simple point right, which likely points to outsourcing. Why would Google do this? And why wouldn’t it ensure that a better job was done? Because, really, so far the long-overdue conversion to Hanyu Pinyin in Google Maps for Taiwan is something of a botch.

Arrr! In recognition of

Arrr! In recognition of

I didn’t have any luck finding anything in Sin Wenz (

I didn’t have any luck finding anything in Sin Wenz (

![beijing_bookstore sign in a Beijing bookstore reading 'Education Theury' [sic]](https://pinyin.info/news/news_photos/2009/07/beijing_bookstore.jpg)