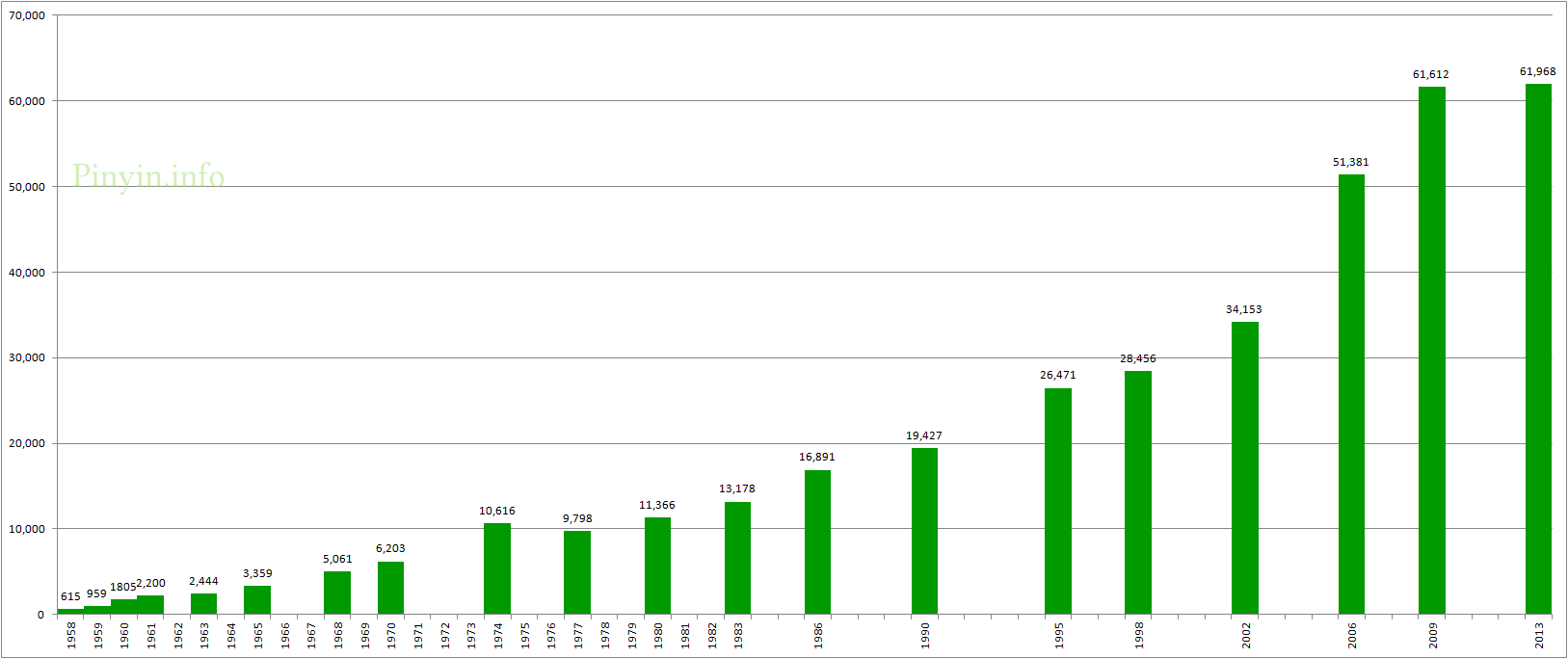

Today I’m continuing my look at the U.S. high school Advanced Placement foreign language exams, focusing especially on the AP exam in Chinese Language and Culture. (See also AP exams: using highest and lowest scores to look at the case of Chinese.)In the graphs below, “Chinese” is the first column on the left.

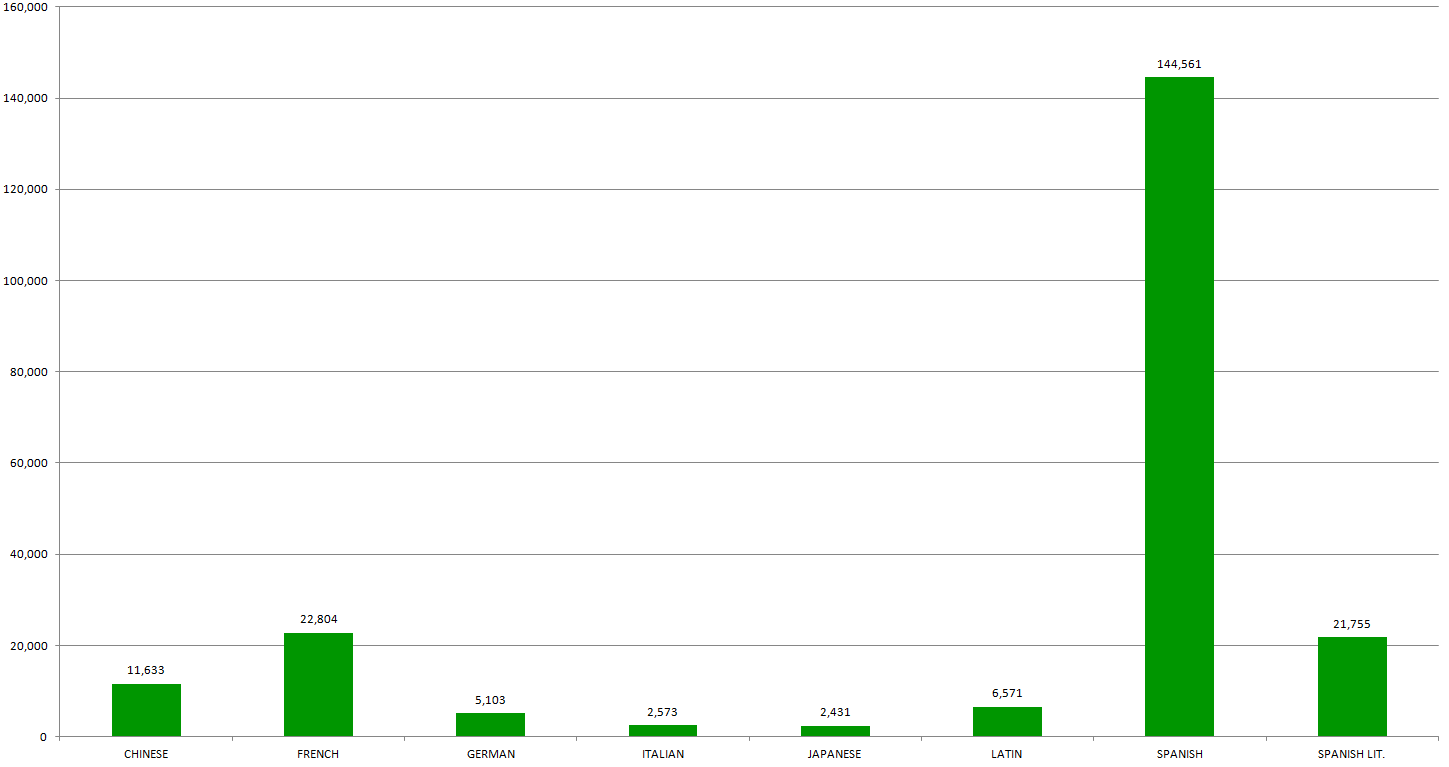

The first and obvious point from graphing the numbers of high school students from the class of 2015 who took an AP foreign language exam is the dominance of Spanish. Combined, the exams for Spanish Language and Spanish Literature outnumber all of the other language exams put together … times three.

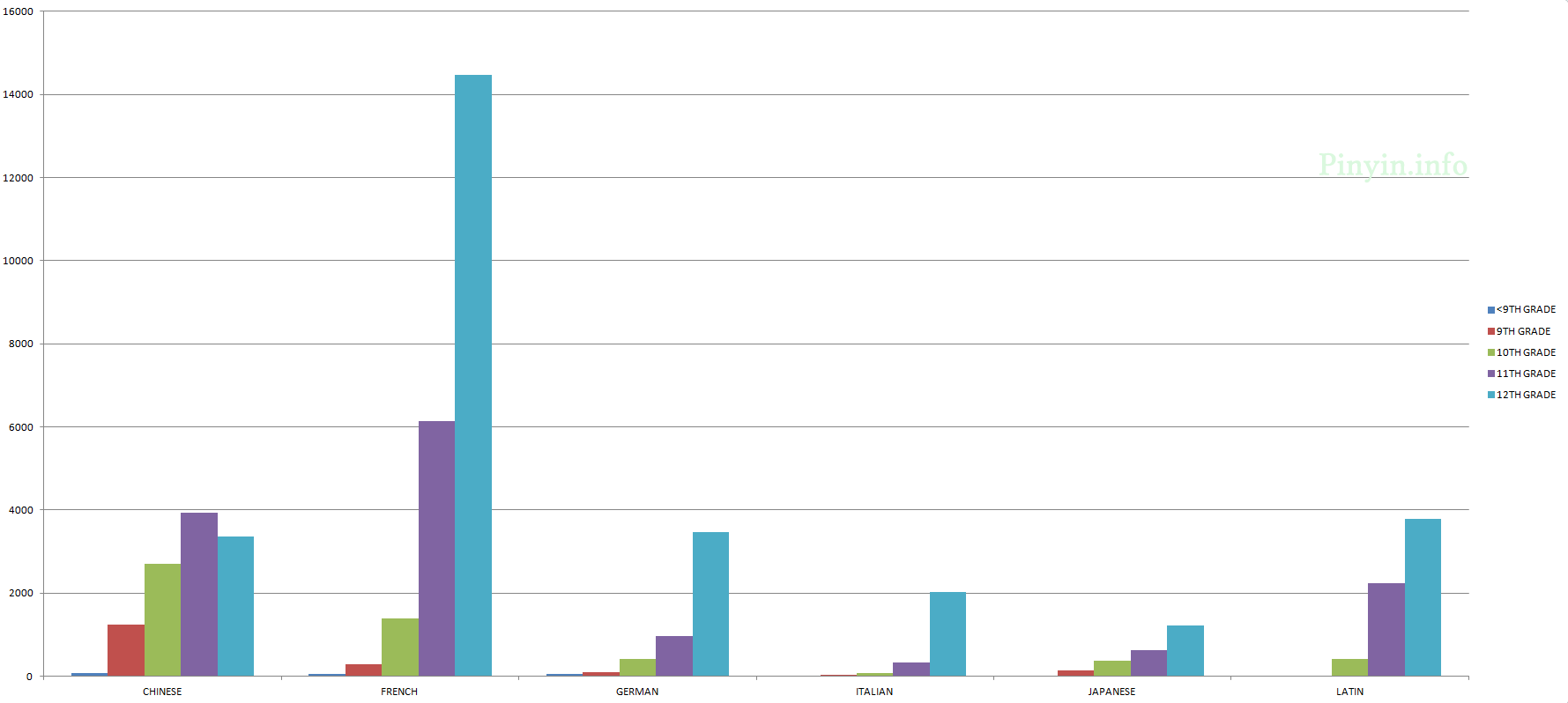

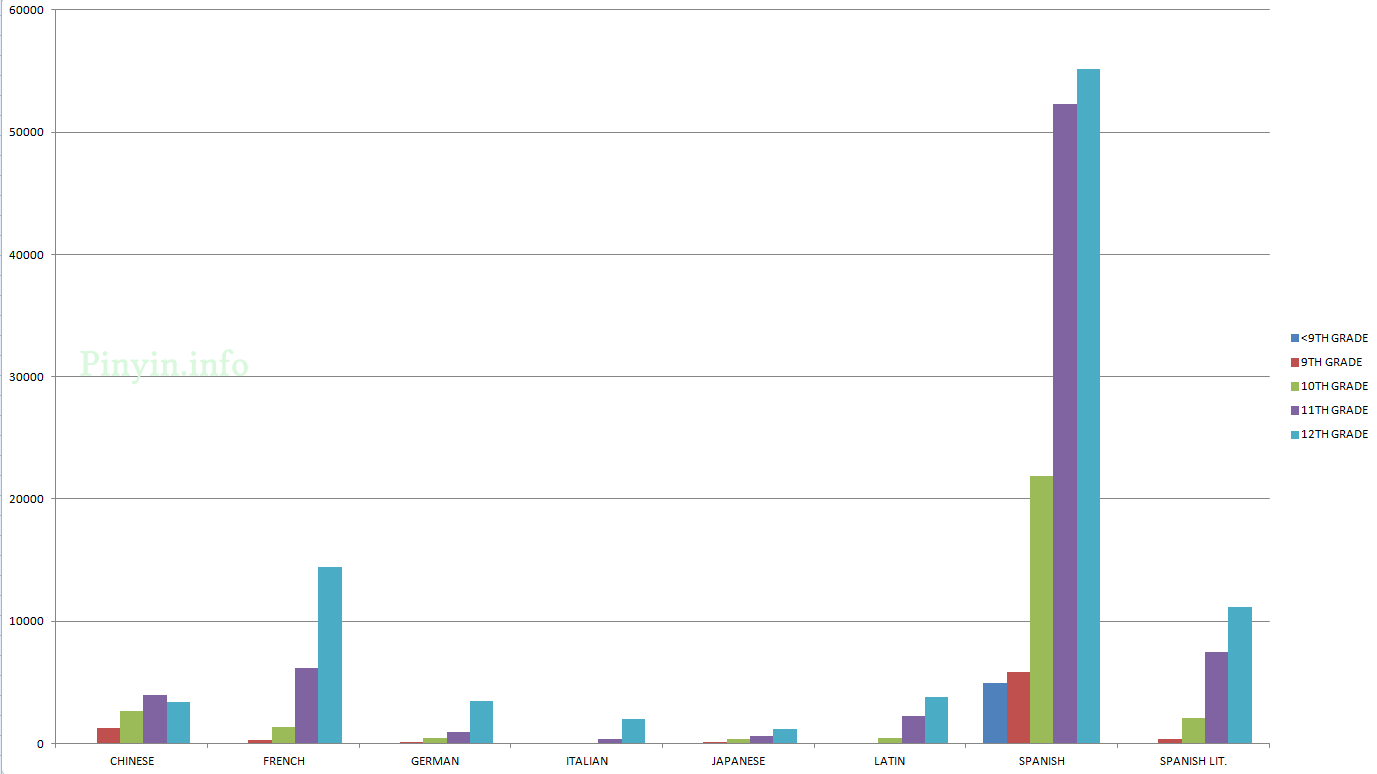

Now let’s look at the figures above broken down into the grade during which people took the exam. As you can see, there’s something different about when people take the Chinese exam. For all other foreign languages, most people take the exam their senior year. But the Chinese Language and Culture exam is most often taken by juniors.

That’s a little lopsided. So let’s take Spanish and Spanish Lit. out of the mix so we can compare the other languages more easily.

In just a few years Chinese has grown to be the third-most popular AP foreign language exam, behind Spanish and French. OK: way, way behind Spanish and about half of the number that French has. And Chinese comes in fourth if you count Spanish Literature. Still, Chinese now has more test takers than German. And it has more than Latin, Italian, and Japanese put together. But — you knew there’d be a but — the numbers for the AP Chinese Language and Culture exam are relatively large because most of the people who take it already know the language and didn’t learn it in an AP class. That is reflected in the charts above showing when people took the exam. (Note that Spanish also has a relatively high number of juniors taking the exam.)

The closest measure we have for native speakers and others with a much higher level of exposure to the language in question than other students is what students indicate themselves to the College Board on their answer sheets. Here’s how the College Board defines a “standard” student: They “generally receive most of their foreign language training in U.S. schools. They did not indicate on their answer sheet that they regularly speak or hear the foreign language of the exam, or that they have lived for one month or more in a country where the language is spoken.”

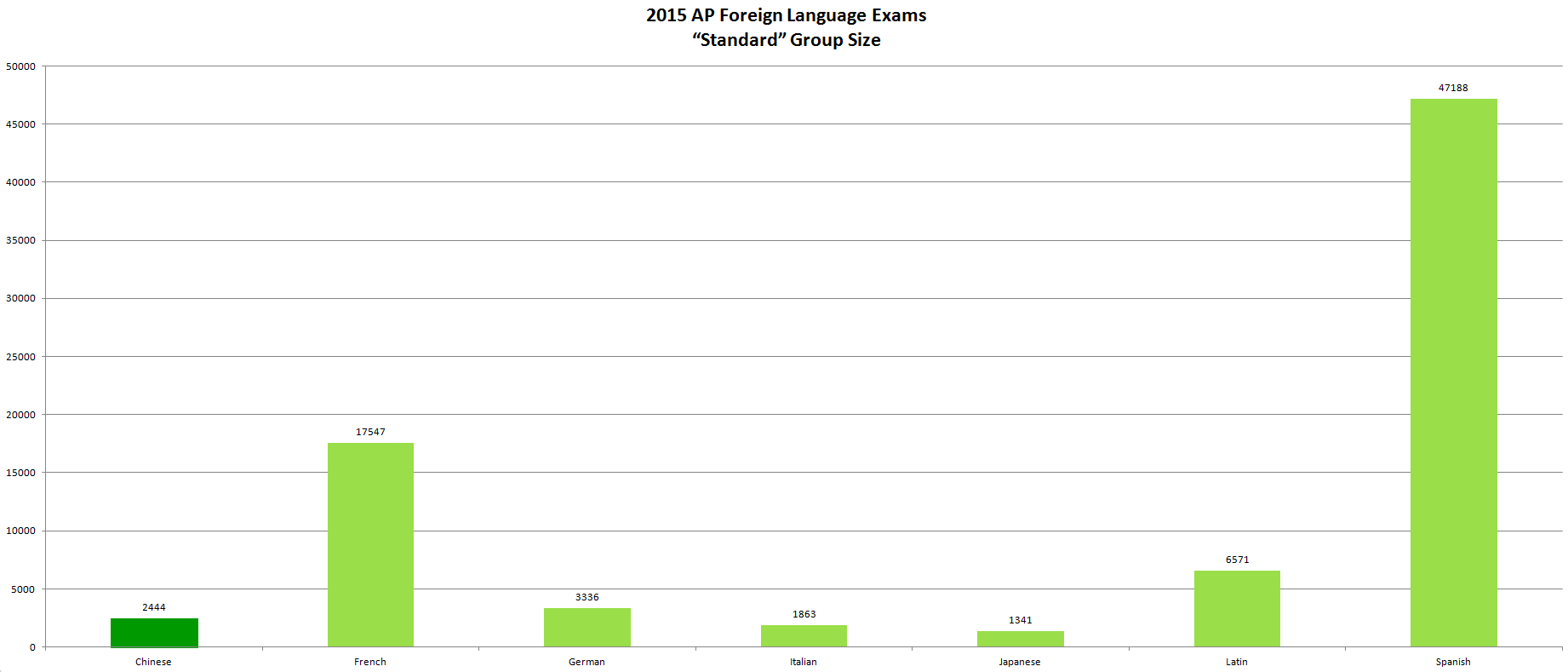

Here are the numbers for “standard” students in 2015 across various languages.

In this, Chinese drops from third place to fifth, behind Spanish, French, Latin (which is without a question on the standard group), and German, but still ahead of Italian and Japanese. When all test-takers are considered, AP exams in French outnumber those in Chinese by a little less than 2:1, which sounds very impressive (and, to some degree, it is). But when only the standard groups are considered, AP exams in French outnumber those in Chinese by more than 7:1.

Later in this series, we’ll look further at both the standard group and those not in it.

Today’s selection from Yin Binyong’s Xīnhuá Pīnxiě Cídiǎn (《新华拼写词典》 / 《新華拼寫詞典》) deals with how to write Mandarin’s various de‘s, mood particles, and interjections.

Today’s selection from Yin Binyong’s Xīnhuá Pīnxiě Cídiǎn (《新华拼写词典》 / 《新華拼寫詞典》) deals with how to write Mandarin’s various de‘s, mood particles, and interjections.