Tomorrow, February 7, 2024, Mark O’Neill will give an online talk on “The Father of China’s Pinyin System: Zhou Youguang.” David Moser will moderate. The talk is sponsored by the Royal Asiatic Society, Beijing.

General admission is 100 RMB.

Tomorrow, February 7, 2024, Mark O’Neill will give an online talk on “The Father of China’s Pinyin System: Zhou Youguang.” David Moser will moderate. The talk is sponsored by the Royal Asiatic Society, Beijing.

General admission is 100 RMB.

Yesterday (January 13, 2018), Google marked the 112th birthday of Zhou Youguang, the father of Hanyu Pinyin, with one of its doodles. (Click the image to see the animated version.)

Google’s description didn’t note Zhou’s remarkable longevity. He lived to see his 111th birthday!

One bit of the description is misleading: “[Hanyu Pinyin] bridged multiple Chinese dialects with its shared designations of sound.” First, what are commonly referred to as “dialects” are actually separate languages (e.g., Cantonese, Hakka, Hoklo). Second, Hanyu Pinyin is designed for modern standard Mandarin, not for other languages, though it could be used as the basis for writing systems for Sinitic languages other than Mandarin; this did not happen on a wide scale, however, because the government of the People’s Republic of China has worked to suppress Sinitic languages other than Mandarin — to say nothing of the languages of Tibetans and other minorities.

A few points are noteworthy about the sketches, specifically the inclusion of Gǔgē, the Mandarin name for Google, written in zhuyin fuhao (a.k.a. bopomofo) (ㄍㄨˇㄍㄜ) and Gwoyeu Romatzyh (guuge) — the doubled vowel indicates third tone.

It’s also interesting that the doodle was shown on Google in Japan, China, and Singapore, but not in Taiwan, where Hanyu Pinyin is official but generally used on street signs rather than in personal names.

Thanks to Alex for the tip.

Zhou Youguang, who is often called the “father of Hanyu Pinyin,” died earlier today.

He lived to the age of 111. He was “the man God forgot,” he liked to joke. And he did like to laugh. His sense of humor, which he kept despite some of the trials he suffered, no doubt helped him flourish so long.

He was most remarkable, however, not for his longevity but for his monumental contribution to literacy, his dedication to helping others, and his sense of justice.

I’ll add more information later.

RIP.

I’ve just added to Pinyin.info the tenth and final issue (December 1989) of the seminal journal Xin Tang. I strongly encourage everyone to take a look at it and some of the other issues. Copies of this journal are extremely rare; but their importance is such that I’ll be putting all of them online here over the years.

Although I’m giving the table of contents in English, the articles themselves are in Mandarin and written in Pinyin.

The ninth issue of Xin Tang is now available here on Pinyin.info. The journal, which was published in the 1980s, is in and about romanization. By this point in its publication most everything in it was written in Hanyu Pinyin (as opposed to Gwoyeu Romatzyh or another system). Xin Tang is interesting not just as a forum in which one can read original content in Pinyin. It’s also important for the history of Pinyin itself. Over the course of its nearly decade-long run, one can see its authors (including many top people in romanization) working out Pinyin as a real script.

Xin Tang no. 9 (December 1988)

Here’s an English version of the table of contents. Note that the articles themselves are, for the most part, in Mandarin.

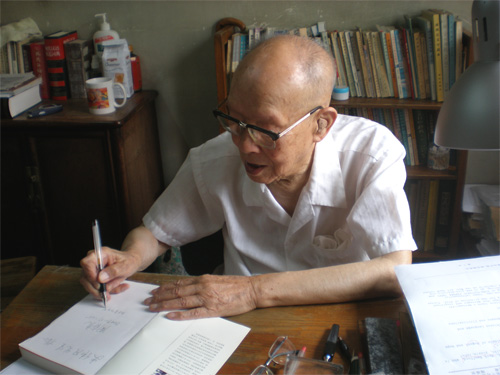

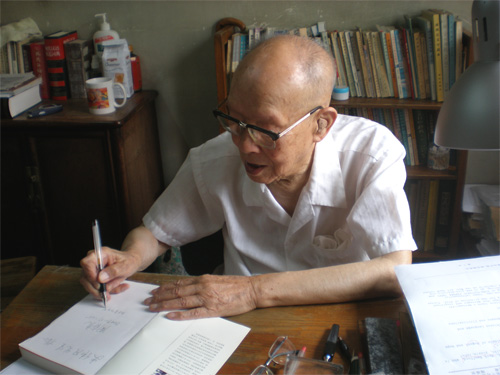

I’d like to share a note that Zhou Youguang, the father of Pinyin, very generously wrote to me last week.

感谢Mark Swofford 先生的拼音网站,把拼音用做学习 中文的工具.我祝贺Swofford 先生的工作获得成功!

语言使人有别于禽兽,

文字使文明别于野蛮,

教育使先进有别于落后。周有光

2012-03-02

时年107岁

Gǎnxiè Mark Swofford xiānsheng de pīnyīn wǎngzhàn, bǎ pīnyīn yòngzuò xuéxí Zhōngwén de gōngjù. Wǒ zhùhè Swofford xiānsheng de gōngzuò huòdé chénggōng!

Yǔyán shǐrén lèibié yú qínshòu,

wénzì shǐ wénmíng bié yú yěmán,

jiàoyù shǐ xiānjìn bié yú luòhòu.Zhōu Yǒuguāng

2012-03-02

shí nián 107 suì

The New York Times has just published a profile of Zhou Youguang, who is often called “the father of Pinyin” (though he modestly prefers to stress that others worked with him): A Chinese Voice of Dissent That Took Its Time.

This profile focuses not only on Zhou’s role in the creation of Hanyu Pinyin but also on his political views, which he has become increasingly public with.

About Mao, he said in an interview: “I deny he did any good.” About the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre: “I am sure one day justice will be done.” About popular support for the Communist Party: “The people have no freedom to express themselves, so we cannot know.”

As for fostering creativity in the Communist system, Mr. Zhou had this to say, in a 2010 book of essays: “Inventions are flowers that grow out of the soil of freedom. Innovation and invention don’t grow out of the government’s orders.”

No sooner had the first batch of copies been printed than the book was banned in China.

Although the reporter’s assertion, following the PRC’s official figures, that “China all but stamp[ed] out illiteracy” is well wide of the mark, there is no denying Pinyin’s crucial role in this area. I recommend reading the whole article.

Louisa Lim had a story on National Public Radio yesterday about Zhou Youguang (周有光 / Zhōu Yǒuguāng), who’s often referred to as the father of Pinyin.

Most stories in the mass media about him focus on just two things, which might be summarized as “pinyin” and “wow, he’s really old.” This story, however, draws welcome notice to some some other things about him, as the title reveals: At 105, Chinese Linguist Now A Government Critic. (There’s a link to the audio version near the top of the page. Zhou can be heard in the background speaking Mandarin — though his English is excellent.)

The article also provides a link to his blog: Bǎisuì xuérén Zhōu Yǒuguāng de bókè (百岁学人周有光的博客).

Further reading:

Hat tip to John Rohsenow.