傾耳而聽

listen attentively

As I often note, apostrophes are used in only about 2 percent of words as written in Hanyu Pinyin. But when they’re needed, they’re needed. Don’t skip them.

A few years back, someone wrote to me to ask about multiple apostrophes in Pinyin. I dug through a 2019 edition of the CC-CEDICT (2019-11-12 04:41:56 GMT) for an answer. But I don’t think I ever posted my findings online. It’s time to rectify that.

CC-CEDICT is not an ideal source in terms of words, because some entries are phrases rather than single words, though they are not marked separately than words, which means that some entries might be better off with spaces rather than apostrophes, which would reduce the apostrophe count and percentage.

So, with that in mind, of the file’s 117,579 entries, 3,006 needed apostrophes, or 2.56 percent.

No entry needed three or more apostrophes.

Only 52 entries needed two apostrophes, or 0.04% of the total (1 per 2,261 entries).

Most of those were just Mandarinized foreign proper nouns. For example:

- Ā’ěrjí’ěr: Algiers, capital of Algeria/ 阿爾及爾 阿尔及尔

- Āi’ěrduō’ān: Erdogan (name)/Recep Tayyip Erdoğan (1954-), Turkish politician, prime minister from 2003/ 埃爾多安 埃尔多安

- Běi’ài’ěrlán: Northern Ireland/ 北愛爾蘭 北爱尔兰

- Bì’ěrbā’è: Bilbao (city in Spain)/ 畢爾巴鄂 毕尔巴鄂

- Dá’ěrfú’ěr: Darfur (western province of Sudan)/ 達爾福爾 达尔福尔

- Dá’ěrfù’ěr: Darfur, region of west Sudan/ 達爾富爾 达尔富尔

- fēi’ābèi’ěr: (math.) non-abelian/ 非阿貝爾 非阿贝尔

- Fèi’àoduō’ěr: Theodor of Fyodor (name)/ 費奧多爾 费奥多尔

- gǔ’ānxiān’àn: glutamine (Gln), an amino acid/ 谷氨酰胺 谷氨酰胺

- Láiwàng’è’ěr: Levanger (city in Trøndelag, Norway)/ 萊旺厄爾 莱旺厄尔

- Léi’ā’ěrchéng: Ciudad Real/ 雷阿爾城 雷阿尔城

- Luójié’ài’ěrzhī: Raziel, archangel in Judaism/ 羅潔愛爾之 罗洁爱尔之

- Mài’ěrwéi’ěr: Melville (name)/Herman Melville (1819-1891), US novelist, author of Moby Dick / 麥爾維爾 麦尔维尔

- Pí’āi’ěr: Pierre (name)/ 皮埃爾 皮埃尔

- Shàng’àisè’ěr: Overijssel/ 上艾瑟爾 上艾瑟尔

- Sīfú’ěrwǎ’ěr: Svolvær (city in Nordland, Norway)/ 斯福爾瓦爾 斯福尔瓦尔

- Sītài’ēnxiè’ěr: Steinkjær (city in Trøndelag, Norway)/ 斯泰恩謝爾 斯泰恩谢尔

- Tèlǔ’āi’ěr: Tergüel or Teruel, Spain/ 特魯埃爾 特鲁埃尔

- Xīn’ào’ěrliáng: New Orleans, Louisiana/ 新奧爾良 新奥尔良

Examples of more regular Mandarin entries with two apostrophes include:

- bái’éyàn’ōu: (bird species of China) little tern (Sternula albifrons)/ 白額燕鷗 白额燕鸥

- báixuě’ái’ái: brilliant white snow cover (esp. of distant peaks)/ 白雪皚皚 白雪皑皑

- chū’ěrfǎn’ěr: old: to reap the consequences of one’s words (idiom, from Mencius); modern: to go back on one’s word/to blow hot and cold/to contradict oneself/inconsistent/ 出爾反爾 出尔反尔

- húnhún’è’è: muddleheaded/ 渾渾噩噩 浑浑噩噩

- pāi’àn’érqǐ: lit. to slap the table and stand up (idiom); fig. at the end of one’s tether/unable to take it any more/ 拍案而起 拍案而起

- qì’áng’áng: full of vigor/spirited/valiant/ 氣昂昂 气昂昂

- qīng’ěr’értīng: to listen attentively/ 傾耳而聽 倾耳而听

- qīqī’ài’ài: stammering (idiom)/ 期期艾艾 期期艾艾

- suíyù’ér’ān: at home wherever one is (idiom); ready to adapt/flexible/to accept circumstances with good will/ 隨遇而安 随遇而安

- xiù’ēn’ài: to make a public display of affection/ 秀恩愛 秀恩爱

- yǐ’échuán’é: to spread falsehoods/to increasingly distort the truth/to pile errors on top of errors (idiom)/ 以訛傳訛 以讹传讹

A few of those present interesting questions in orthography. For example, Xīn’ào’ěrliáng or Xīn Ào’ěrliáng?

But, basically, those entries are outliers. Relatively few words in Pinyin need an apostrophe; only a minute subset of those need two apostrophes; and, to my knowledge, none need three or more apostrophes.

Can you think of any triple-apostrophe words? Sorry, written examples of stuttering don’t count.

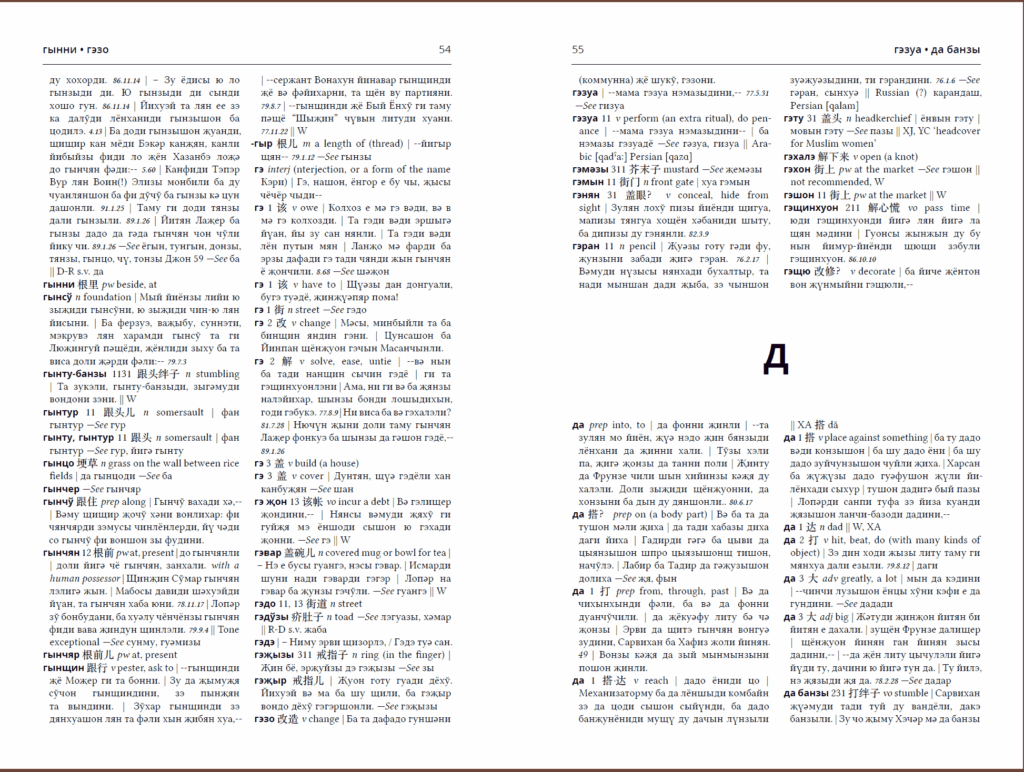

The standard for alphabetically sorting Hanyu Pinyin is given in the ABC dictionary series edited by John DeFrancis and issued by the University of Hawaii Press.

The standard for alphabetically sorting Hanyu Pinyin is given in the ABC dictionary series edited by John DeFrancis and issued by the University of Hawaii Press.

Today’s selection from Yin Binyong’s Xīnhuá Pīnxiě Cídiǎn (《新华拼写词典》 / 《新華拼寫詞典》) deals with how to write Mandarin’s various de‘s, mood particles, and interjections.

Today’s selection from Yin Binyong’s Xīnhuá Pīnxiě Cídiǎn (《新华拼写词典》 / 《新華拼寫詞典》) deals with how to write Mandarin’s various de‘s, mood particles, and interjections.