It’s times like this I especially miss John DeFrancis. How he would have loved this! It’s partially an example of what he dubbed “Singlish” — not Singapore English but Sino-English, the tortured attempt to use Chinese characters to write English. He details this in “The Singlish Affair,” a shaggy dog story that serves as the introduction to his essential work: The Chinese Language: Fact and Fantasy. (And I really do mean essential. If you don’t have this book yet, buy it and read it.)

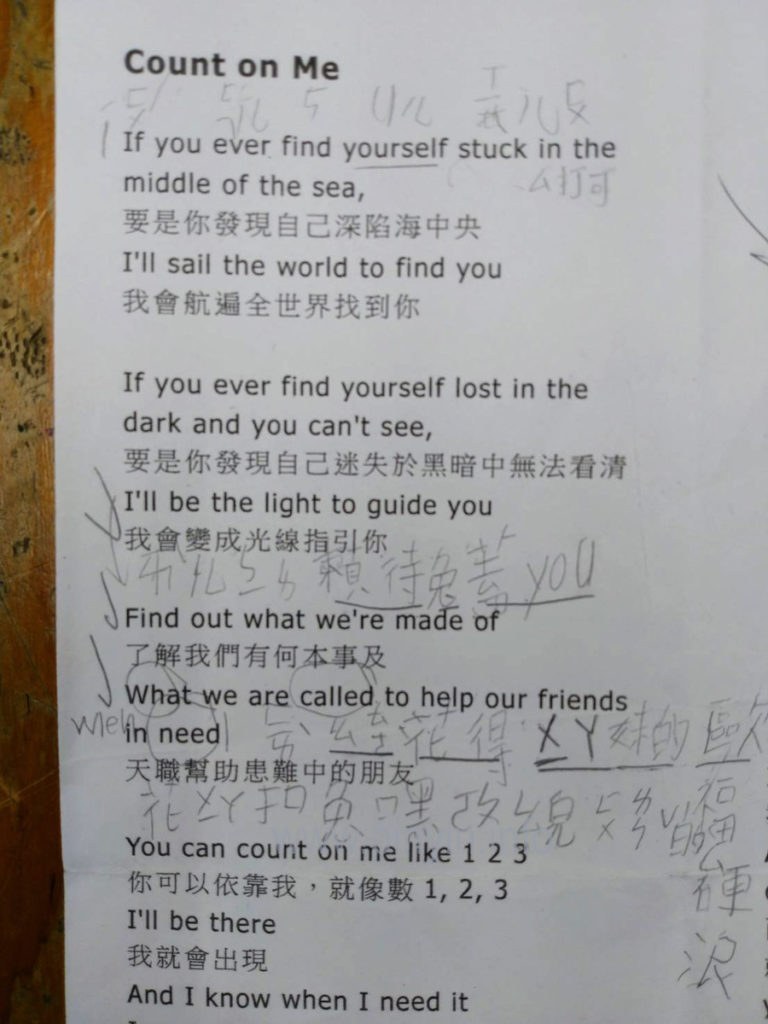

Here are some lyrics from a popular song, “Count on Me,” by Bruno Mars, with a Mandarin translation. The interesting part is that a Taiwanese third-grader has penciled in some phonetic guides for him or herself, using a combination of zhuyin fuhao (aka bopo mofo) (sometimes with tone marks!), English (as a gloss for English! and English pronunciation of some letters and numbers), and Chinese characters (albeit not always correctly written Chinese characters — not that I could do any better myself). Again, this is a Taiwanese third-grader and so is someone unlikely to know Hanyu Pinyin.

“If you ever find yourself stuck”

If |

ㄧˊㄈㄨˊ |

yífú |

| you | ||

| ever | ㄟㄈㄦ | ei-f’er |

find |

5 |

five |

| yourself | Uㄦㄒㄧㄦㄈㄨ | U’er xi’erfu |

stuck |

ㄙ打可 |

s-dake |

“I’ll be the light to guide you.”

I’ll |

ㄞㄦ |

ài’er |

be |

ㄅㄧ |

bi |

| the | ㄌ | l[e] |

light |

賴特* |

laite |

| to | 兔 | tu |

guide |

蓋 |

gai |

you |

you |

you |

“Find out what we’re made of”

Find |

ㄈㄞˋ |

fài |

out |

ㄠㄊㄜ |

ao-t’e |

what |

花得 |

huade |

we’re |

ㄨㄧㄚ |

wi’a |

made |

妹的 |

meide |

of |

歐福 |

oufu |

“When we are called to help our friends in need”

花 |

hua |

|

we |

ㄨㄧ |

wi |

are |

ㄚ |

a |

called |

扣 |

kou |

to |

兔 |

tu |

help |

嘿ㄜㄆ |

hei’e-p[e] |

our |

ㄠㄦ |

ao’er |

friends |

ㄈㄨㄌㄣˇ的ㄙ |

fulen-de-s |

in |

硬 |

ying |

need |

[?] |

[?] |

![Calyx imbricatus, polyphyllus: foliolis interioribus majoribus. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet.... [Sorry, just kidding!] Camellia Japonica. Rose Camellia.](https://pinyin.info/news/news_photos/2012/01/camellia_japonica.jpg)

Today’s selection from Yin Binyong’s Xīnhuá Pīnxiě Cídiǎn (《新华拼写词典》 / 《新華拼寫詞典》) is about writing numbers and measure words.

Today’s selection from Yin Binyong’s Xīnhuá Pīnxiě Cídiǎn (《新华拼写词典》 / 《新華拼寫詞典》) is about writing numbers and measure words.