The Hong Kong government’s Standing Committee on Language Education and Research (“Scolar” — heh) yesterday launched a HK$200 million (US$25.8 million) campaign to help schools use Mandarin as the medium for instruction.

Half of the money will be used to hire extra teachers, with the other half used to bring in mainland teaching experts.

To qualify for this funding, schools must demonstrate competence in teaching “Chinese” in Mandarin and be ready to switch 40 percent of “Chinese language teaching” from Cantonese to Mandarin within three years. The scheme is expected to start at the beginning of the next academic year and last for more than three years.

Each year about 30 primary and 10 secondary schools will be added to the program.

Scolar Chairman Michael Tien Puk-sun said that his committee “has agreed that Putonghua [i.e., Mandarin] should be used as a medium of instruction for Chinese language subjects in the long term.”

This does not bode well for the future of Cantonese.

sources:

- Putonghua scheme confirmed, South China Morning Post, October 31, 2007

- Care needed to make Putonghua plan work, South China Morning Press opinion pages, October 31, 2007

- HK$200m plan to help schools use Putonghua: Bid to limit Cantonese in teaching Chinese language, South China Morning Post, October 30, 2007

The

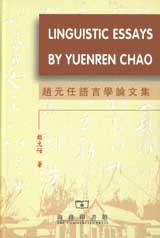

The  Note how the cover of Linguistic Essays, a book printed just last year in China, uses “Yuenren Chao,” the traditional spelling and Western order of his name, rather than “Zhao Yuanren,” the spelling used in Hanyu Pinyin. Also note how the Mandarin title is given in traditional, not simplified, characters: 趙元任語言學論文集, not 赵元任语言学论文集. A nice surprise, on both counts. On the other hand, the botched romanization on the cover of the Mandarin-language collection, which gives “ZHAOYUANREN YUYANXUELUNWENJI” instead of “

Note how the cover of Linguistic Essays, a book printed just last year in China, uses “Yuenren Chao,” the traditional spelling and Western order of his name, rather than “Zhao Yuanren,” the spelling used in Hanyu Pinyin. Also note how the Mandarin title is given in traditional, not simplified, characters: 趙元任語言學論文集, not 赵元任语言学论文集. A nice surprise, on both counts. On the other hand, the botched romanization on the cover of the Mandarin-language collection, which gives “ZHAOYUANREN YUYANXUELUNWENJI” instead of “