About a year ago (which is roughly how overdue this post is), a commenter noted that some Chinese publishers “are convinced that Pinyin must be printed with ɑ (single-story „Latin alpha“, as opposed to double-story a), and with ɡ (single story; not double story g).”

About a year ago (which is roughly how overdue this post is), a commenter noted that some Chinese publishers “are convinced that Pinyin must be printed with ɑ (single-story „Latin alpha“, as opposed to double-story a), and with ɡ (single story; not double story g).”

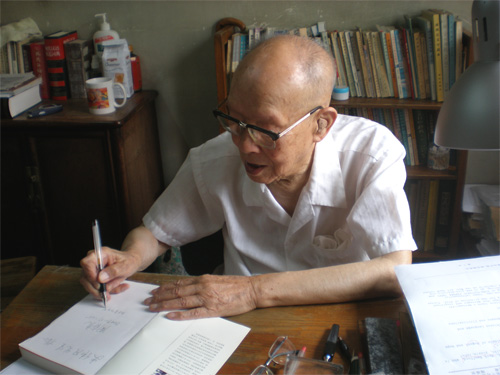

But does Hanyu Pinyin in fact call for this longstanding Chinese habit of bad typography? This was one of the first questions I asked of Zhou Youguang, the father of Hanyu Pinyin, when I met with him: Are those who insist upon the ɑ-style letter correct?

“Oh, no,” Zhou replied. “That ‘ɑ’ is just for babies!” And he laughed that wonderful laugh of his that no doubt has contributed to his remarkable longevity.

Zhou was referring to the facts that the “ɑ” style of letter is usually found specifically in books for infants … and that this style generally does not belong elsewhere. In fact, ɑ and ɡ (written thusly, as opposed to g) are often referred to as infant characters. A variant of the letter y is sometimes included in this set.

Letters in that style are also found in the West — but almost always in books for toddlers, and often not even in those. Furthermore, even in those cases the use of such letters appears to have no positive effect on children’s reading.

The correct-style letters for Pinyin are the same as those for English, Zhou stated.

I hope that anyone who has been using “ɑ” will both officially and in practice switch to “a”. It’s long past time that the supposed rule calling for “ɑ” was treated as a dead letter.

Long live good typography!

I didn’t have any luck finding anything in Sin Wenz (

I didn’t have any luck finding anything in Sin Wenz (

![beijing_bookstore sign in a Beijing bookstore reading 'Education Theury' [sic]](https://pinyin.info/news/news_photos/2009/07/beijing_bookstore.jpg)

Friday, January 13, is Zhou Youguang’s 101st birthday. Zhou is one of the main people behind the creation of

Friday, January 13, is Zhou Youguang’s 101st birthday. Zhou is one of the main people behind the creation of