Imagine taking everyone in the United States with the family name of Johnson, Williams, Jones, Brown, Davis, Miller, Wilson, Moore, Taylor, or Anderson … and giving them all the new family name of “Smith.” Then add to the Smiths everyone surnamed Thomas, Jackson, White, Harris, Martin, Thompson, Garcia, Martinez, Robinson, Clark, Rodriguez, Lewis, Lee, Walker, Hall, Allen, Young, Hernandez, King, Wright, and Lopez. Those are, in descending order beginning with Smith, the 32 most common family names in the United States. It takes all of those names together to reach the same frequency that the name “Chen” (Hoklo: Tân) has in Taiwan.

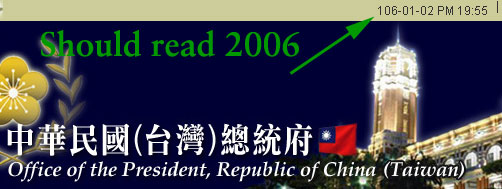

Chen covers 10.93 percent of the population here, according to figures released by Chih-Hao Tsai based on the recent release of the names of the 81,422 people who took Taiwan’s college entrance exam this year.

By way of additional contrast, Smith, the most common family name in the United States, covers just 1.00 percent of the population there.

In Taiwan, the 10 most common family names cover half (50.22 percent) of the population. Covering the same percentage in the United States requires the top 1,742 names there. And covering the same percentage as Taiwan’s top 25 names (74.17 percent) requires America’s top 13,425 surnames.

So if you’re just getting started in Mandarin, consider that you’ll get a lot of mileage out of memorizing the tones for the top ten names.

| family name (Mandarin form) |

spelling usually seen in Taiwan |

percent of total |

cumulative percentage |

| Chén |

Chen |

10.93% |

10.93% |

| Lín |

Lin |

8.36% |

19.29% |

| Huáng |

Huang |

6.06% |

25.35% |

| Zhāng |

Chang |

5.39% |

30.74% |

| Lǐ |

Li, Lee |

5.20% |

35.94% |

| Wáng |

Wang |

4.20% |

40.14% |

| Wú |

Wu |

4.03% |

44.17% |

| Liú |

Liu |

3.18% |

47.36% |

| Cài |

Tsai |

2.86% |

50.22% |

| Yáng |

Yang |

2.64% |

52.86% |

| Xǔ |

Hsu |

2.32% |

55.18% |

| Zhèng |

Cheng |

1.86% |

57.05% |

| Xiè |

Hsieh |

1.77% |

58.82% |

| Qiū |

Chiu |

1.50% |

60.32% |

| Guō |

Kuo |

1.48% |

61.79% |

| Zēng |

Tseng |

1.45% |

63.24% |

| Hóng |

Hung |

1.40% |

64.64% |

| Liào |

Liao |

1.38% |

66.02% |

| Xú |

Hsu |

1.33% |

67.35% |

| Lài |

Lai |

1.32% |

68.66% |

| Zhōu |

Chou |

1.24% |

69.90% |

| Yè |

Yeh |

1.18% |

71.08% |

| Sū |

Su |

1.17% |

72.25% |

| Jiāng |

Chiang |

0.97% |

73.22% |

| Lǚ |

Lu |

0.94% |

74.17% |

For those wanting the Taiwanese (Hoklo) forms of these names, see Tailingua’s list of Common Family Names in Taiwan.

On the other hand, common given names have much greater variety in Taiwan than in America, especially in the case of males. In the United States the top 10 names for males cover 23.185 percent of the male population, and the top 10 names for females cover 10.703 percent of the population. In Taiwan, however, the top 10 given names (male and female together) cover just 1.49 percent of the population.

sources:

further reading:

- China to enact rules on characters in personal names: PRC official, Pinyin News, March 18, 2006

- Chinese names, stroke counts, and fengshui, Pinyin News, January 2006

- officials nix change to grandiose personal name, Pinyin News, January 5, 2006

During an extremely brief trip a few weeks ago to

During an extremely brief trip a few weeks ago to