I didn’t have any luck finding anything in Sin Wenz (Lādīnghuà Xīn Wénzì / 拉丁化新文字), despite trips to several large used book stores. (Fortunately, the Internet is now providing some leads. Thanks, Brendan and Joel!) But I did find some other books to bring home.

I didn’t have any luck finding anything in Sin Wenz (Lādīnghuà Xīn Wénzì / 拉丁化新文字), despite trips to several large used book stores. (Fortunately, the Internet is now providing some leads. Thanks, Brendan and Joel!) But I did find some other books to bring home.

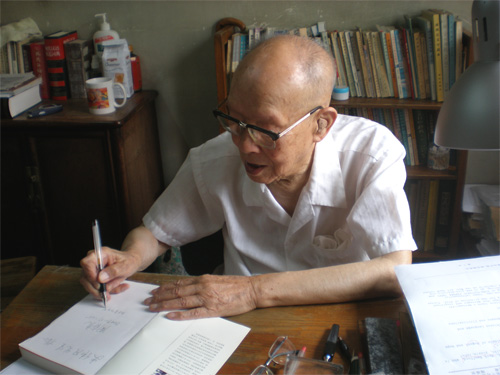

I acquired lots of books by Zhou Youguang, not all of which focus primarily on linguistics:

- Hànyǔ Pīnyīn wénhuà jīnliáng (汉语拼音文化津梁)

- Yǔyán wénzì xué de xīn tànsuǒ (语言文字学的新探索)

- Zhōu Yǒuguāng bǎi suì kǒushù (周有光百嵗口述)

- Bǎi suì xīn gǎo (百嵗新稿)

- Yǔyán xiántán (语言闲谈)

Other than the Zhou Youguang books, here are my favorite finds of the trip, as they are for the most part in correctly word-parsed Hanyu Pinyin (with Hanzi underneath), along with a few notes in English:

- All three volumes in the “torrents” trilogy (Jīliú sānbùqǔ / 激流三部曲) by Bā Jīn (巴金 / Ba Jin):

- Jiā (家/Family). One of the classics of modern Chinese literature.

- Chūn (春/Spring)

- Qiū (秋/Autumn)

- Wéichéng (圍城/围城/ The Besieged City (a.k.a. Fortress Besieged)), by Qián Zhōngshū (錢鍾書/钱锺书/Qian Zhongshu). This is a terrific novel. I’m looking forward to reading it in Pinyin, albeit in an abridged edition.

I’ll soon be posting more about the above books with Pinyin, so watch this site for updates. Really, this is gonna be good.

Although this collection of Y.R. Chao says it’s volume 15, it’s actually two books:

- Zhào Yuánrèn quánjí, dì 15 juàn (趙元任全集第15卷)

Some more titles:

- Measured Words: The Development of Objective Language Testing, by Bernard Spolsky

- Pǔtōnghuà shuǐpíng cèshì shíshī gāngyào (普通話水平測試實施綱要). Now with the great smell of beer! Sorry, Brendan, I owe you one — more than one, actually.

The following I bought because Yin Binyong, the scholar primarily responsible for Hanyu Pinyin’s orthography, is the author of these titles from Sinolingua’s series of Bógǔtōngjīn xué Hànyǔ cóngshū (“Gems of the Chinese Language through the Ages” (their translation)), all of which are in Mandarin (Hanzi) and English, with Pinyin only for the sayings being illustrated:

- 100 Pearls of Chinese Wisdom (Yànyǔ 100)

- 100 Chinese Two-part Allegorical Sayings

- 100 Common Chinese Idioms and Set Phrases (Chéngyǔ 100 / 成語 / 成语)

Other:

- Chinese-English Dictionary of Polyphonic Characters (Duō yīn duōyì zì Hàn-Yīng cídiǎn / 多音多义字汉英词典), by Roderick S. Bucknell

- Hànyǔ zìmǔcí cídiǎn (Chinese Lettered Words Dictionary / 汉语字母词词典), by Liú Yǒngquán (刘涌泉 / Liu Yongquan)

And finally:

- Xīnhuá pīnxiě cídiǎn (新華拼寫詞典), by Yin Binyong.

Of course I already have that one — more than one copy, in fact. But it’s always good to have more than one spare when it comes to one of the two most important books on Pinyin orthography. I really need to follow up on my requests to use excerpts from this book, as it is the only major title missing from my list of romanization-related books (though it’s in Mandarin only).

![beijing_bookstore sign in a Beijing bookstore reading 'Education Theury' [sic]](https://pinyin.info/news/news_photos/2009/07/beijing_bookstore.jpg)

I’ve been reading

I’ve been reading