Raymond Huo, who served as a member of New Zealand’s parliament from 2008 to 2014, was born in China and moved to New Zealand twenty-one years ago from Beijing. His biography at the New Zealand Chinese Language Week Charitable Trust, an organization at which he is a co-chairman, states that he “has published seven books including two Chinese-English dictionaries as joint editor/translator.”

So when you hear that he is unhappy about how Statistics New Zealand is handling Mandarin, Cantonese, etc., in its count of languages, you might be inclined to think he is an expert who is battling ignorance in the bureaucracy. But read on.

“Treating Mandarin, Yue or other Chinese dialects as independent languages is deeply flawed,” Mr Huo said.

“It is similar to making statistical inferences about the difference between Northern English, Oceania English and Indian English, or … between pub talk and the King’s English.

“As such, English may not be the most widely spoken language if each ‘dialect’ was treated as an independent language as in the case of Mandarin and Cantonese.”

This is simply wrong. English as spoken in India, English as spoken in Oceania, and English as spoken elsewhere are all one language. Mandarin and Cantonese are not.

As expected, here comes something about Chinese characters.

The Chinese written script is broadly the same, but a single character can be pronounced in over 1000 different ways across China, according to Mr Huo.

That, however, doesn’t make “Chinese” one language. And focusing on Chinese characters is often a sign that someone has lost track of the language itself — or languages themselves, in this case.

Huo said the ranking order of English, te reo Maori, Samoan, and Hindi as the top four most spoken languages in New Zealand by Statistics NZ was “incorrect, misleading and deeply flawed.” He wants them all counted together, which would move “Chinese” into third place.

Census general manager Denise McGregor, however, said it is important to have a system of classification that enables languages to be either grouped or looked at individually.

“It’s incredibly useful to know that in a school zone, or at a specific library, or on a particular bus route there will be people who speak specifically Mandarin or Chinese,” she said.

“Just knowing they speak ‘Chinese’ isn’t likely to be as useful in targeting services.”

In the last Census, 52,263 people spoke Northern Chinese which includes Mandarin, 44,625 spoke Yue that includes Cantonese and 42,750 spoke a “Sinitic” language.

Mrs McGregor said of the 171,204 people in New Zealand of Chinese ethnicity, 45,216 were born here.

“The majority of these people do not speak any language other than English,” she said.

“We think the rich picture of the different Chinese languages and dialects is a valuable thing to have.”

Amen to that last thought. And I welcome the use of the phrase Sinitic language.

The author of the news article on this spoke with several other people.

David Soh, editor for Auckland-based Chinese language daily Mandarin Pages, said the Census figures for Mandarin speakers were “too low” to be correct.

“The figure that just over a quarter of the Chinese population are Mandarin speakers sounds too low to be accurate or true,” Mr Soh said.

“The fact is Chinese who speak Chinese dialects are often also able to converse in Mandarin, but the Census figure doesn’t seem to reflect that.”

AUT’s head of the School of Language and Culture, Sharon Harvey, said linguists would consider Chinese dialects as independent languages.

“It suits the Chinese Government to say all these languages are ‘only’ dialects but most linguists would say many are languages in their own right.”

Cantonese is a language with nine spoken tones but in Mandarin there are four, said Dr Harvey, and it would be hard to learn Cantonese and “make all those sounds” if someone hasn’t learned them as a child.

The article closes with some figures, taken from New Zealand’s Census 2013, of possible interest:

NEW ZEALAND CHINESE BY NUMBERS

- 171,204 — population total

- 122,964 — speak at least one or more Chinese languages

- 45,216 — NZ born, most speak only English

- 52,263 — speak Northern Chinese, including Mandarin

- 44,625 — speak Yue, including Cantonese

- 42,750 — speak a Sinitic language without further defining

source: How many people in NZ speak Chinese?, New Zealand Herald, December 3, 2015

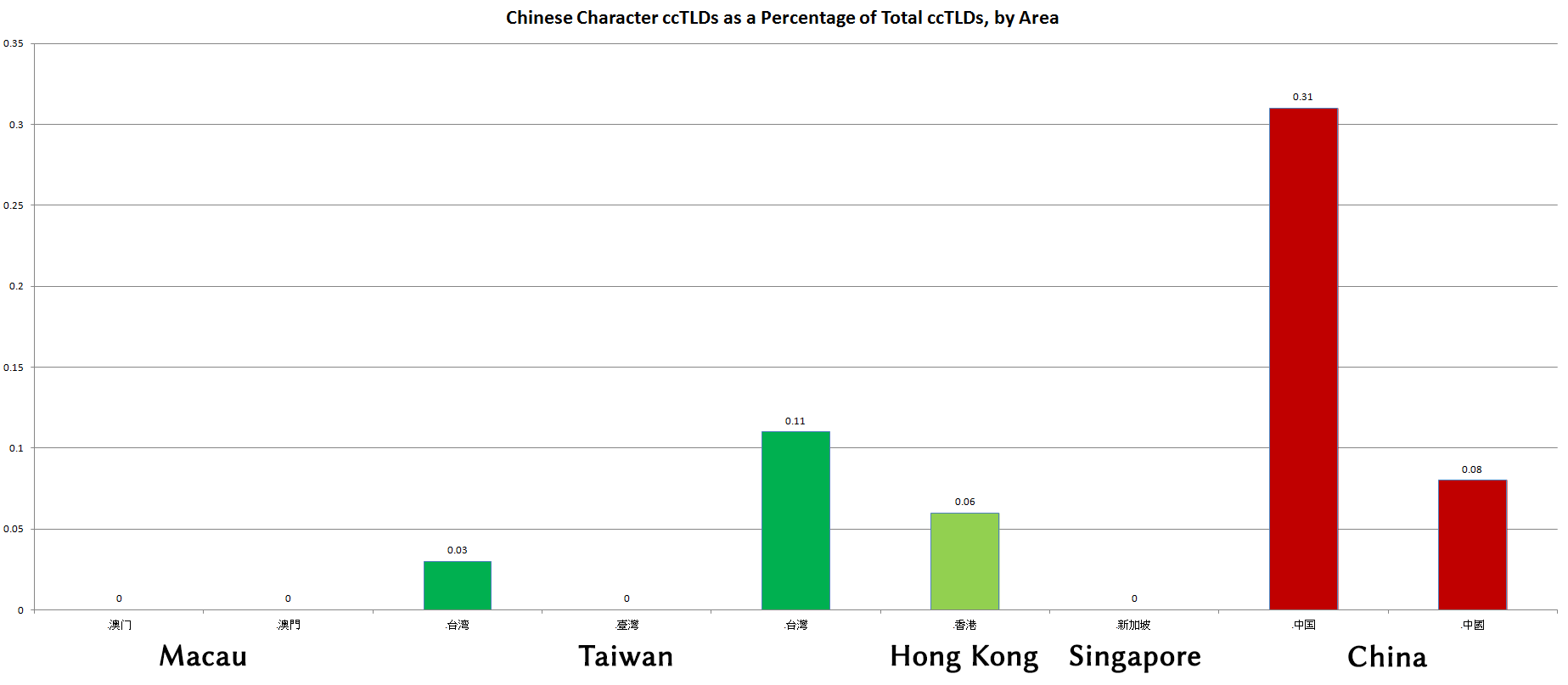

domains compare with the use of .tw domains?

domains compare with the use of .tw domains?  ), so it is omitted here.

), so it is omitted here. and

and  , so those figures are still at zero.

, so those figures are still at zero.  ccTLD, even though the Ma administration, which was in power when Taiwan’s ccTLDs went into effect, officially prefers the more complex form of

ccTLD, even though the Ma administration, which was in power when Taiwan’s ccTLDs went into effect, officially prefers the more complex form of  .

.