The following is a guest post by Prof. Victor H. Mair of the University of Pennsylvania.

——————

Anyone who has taken it upon him/herself to become literate in Chinese characters realizes what a tremendous commitment is required to master the thousands of different graphs that are necessary for reading and writing. Great as the initial expenditure of time and energy is, one must continue to practice reading and writing the characters on an almost daily basis if one is to maintain a workable degree of proficiency. Furthermore, since character production is a skill that requires a high level of neuro-muscular coordination, failure to practice them regularly inevitably results in a rapid deterioration of the ability to write with facility.

In the world of the 21st century, however, there are countless distractions that compete with the Chinese script for the attention of its users: TV, movies, computers, cell phones, video games, iPods, sports, music, dance, and so forth. Every minute or hour devoted to such devices and diversions means less time for practicing the demanding script. In addition, many of these competitors directly or indirectly displace or obviate the script itself. For example, the vast majority of Sinitic language inputting for computers is done via pinyin (Romanization), and the same is true for short text messaging on cell phones which is so ubiquitous in East Asia. Countless studies and endless testimonies from individual users have shown that reliance on computers and other electronic devices to produce written character texts dramatically reduces the ability of users of the Chinese script to form the characters accurately and, to a lesser extent, even diminishes a reader’s ability to distinguish characters.

Some of this was pointed out already in Jennifer 8. Lee’s lengthy and well-researched article entitled “Where the PC Is Mightier Than the Pen: In China, Computer Use Erodes Traditional Handwriting, Stirring a Cultural Debate,” which appeared in the Technology News section of the New York Times on February 1, 2001. Here’s an abstract of Ms. Lee’s article, which was illustrated with photographs:

Use of computers for word processing appears to be taking a toll on Chinese speakers’ ability to write characters by hand; many Chinese fear that computer could undermine written language, which has great cultural significance for Chinese people, but others say the point of language is communication and nothing more; erosion of traditional handwriting skills arises from forcing complexities of Chinese language to conform to standard Roman-alphabet keyboard.

William Hannas, an expert on East Asian writing systems, has perceptively and persuasively pointed out that character production and recognition are intimately linked:

Educators speak too facilely of the distinction between character “recognition skills” and the skills needed to produce them by hand, as if the two were completely independent. In fact, there is much experimental and anecdotal evidence to support a connection between the two types of skills. As one’s ability physically to write Chinese characters, stroke by stroke, improves, so it seems does one’s ability to recognize them and distinguish one from the other. Conversely, as writing skills deteriorate from lack of practice, so does recognition. Primitive motor skills seem to play a part in reinforcing memory here as in other areas. {Original note: Kaiho Hiroyuki summarizes the results of experiments that demonstrate that character recognition is affected by users’ ability to draw them and that users’ appraisal of a character’s complexity depends more on stroke count than on the number of lines actually present in the character. “Nihongo no hyôki kôdô no ninchi shinrigakuteki bunseki,” Nihongogaku, 6 (1987), 65-71.}

If this phenomenon were related to handwriting specifically, literacy would have been lost in the West entirely by now, for most Westerners do their “writing” today on keyboards. But the fact is, typing has reinforced Westerners’ “hands on” awareness of the language by virtue of the direct one-to-one correspondence between discrete hand motions and the letters that make up the words. Character coding schemes, as we have seen, have little or no direct physical connection with the structure of the character — certainly none that bears any relationship to the specific motor skills that are exercised in forming characters. Although it seems unlikely, for all of the reasons given above, that nonphonetic coding will emerge as the primary means of processing Chinese characters for a significant part of the character-literate East Asian population, if this were to happen, the technique could lead eventually to a deterioration of users’ ability to deal with the characters generally. In other words, the same machines that were supposed to give the characters a new lease on life may contain the seeds of the characters’ destruction. {Asia’s Orthographic Dilemma (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1997), pp. 271-271, 314. 322.}

This is all the more true of phonetic inputting schemes for characters, which — though extremely easy to learn and use — are completely divorced from the shapes of the characters.

The diminution of the ability to produce and recognize characters resulting from electronic interventions has already reached a significant stage. As the number of distractions and displacements increases, which is a virtual certainty considering the rapid pace of invention and the growing impact of such devices, the level of dysfunctionality in character production and recognition is bound to advance from significant to serious.

Such competitors (computers, BlackBerries, and so on) pose far less of a threat to alphabetic scripts than to the characters for the following reasons:

- Alphabetic scripts require a far smaller initial investment and a fraction of the effort for maintenance.

- Many of the electronic devices mentioned above actually reinforce or improve writing in alphabetical scripts (spell checkers, grammar checkers, and so on [e-mail style, of course, is another matter altogether] — there are no comparable tools for Chinese).

- When one forgets how to write a character, one is usually stymied for that particular morpheme, whereas misspelling a word generally presents no obstacle to expression or understanding.

The implications of electronic information processing devices for the Chinese script are only beginning to be felt. As they increase in scope and availability, the adverse effects for character production and recognition will grow exponentially till they reach a genuine crisis.

The Commercial Press has begun issuing a set of the complete works of Y.R. Chao (Zhao Yuanren / 趙元任 / 赵元任). This project, which will comprise some twenty volumes, will contain works in both English and Mandarin Chinese. All of the many fields Chao wrote about will be covered. Letters and journals will also be included, as will sound recordings. Wonderful!

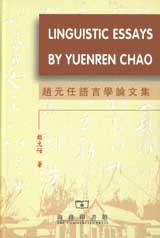

The Commercial Press has begun issuing a set of the complete works of Y.R. Chao (Zhao Yuanren / 趙元任 / 赵元任). This project, which will comprise some twenty volumes, will contain works in both English and Mandarin Chinese. All of the many fields Chao wrote about will be covered. Letters and journals will also be included, as will sound recordings. Wonderful!  Note how the cover of Linguistic Essays, a book printed just last year in China, uses “Yuenren Chao,” the traditional spelling and Western order of his name, rather than “Zhao Yuanren,” the spelling used in Hanyu Pinyin. Also note how the Mandarin title is given in traditional, not simplified, characters: 趙元任語言學論文集, not 赵元任语言学论文集. A nice surprise, on both counts. On the other hand, the botched romanization on the cover of the Mandarin-language collection, which gives “ZHAOYUANREN YUYANXUELUNWENJI” instead of “Zhào Yuánrèn yǔyánxué lùnwénjí,” is particularly inappropriate and painful to look at on a collection of the works of this brilliant linguist. But don’t judge this book by its cover.

Note how the cover of Linguistic Essays, a book printed just last year in China, uses “Yuenren Chao,” the traditional spelling and Western order of his name, rather than “Zhao Yuanren,” the spelling used in Hanyu Pinyin. Also note how the Mandarin title is given in traditional, not simplified, characters: 趙元任語言學論文集, not 赵元任语言学论文集. A nice surprise, on both counts. On the other hand, the botched romanization on the cover of the Mandarin-language collection, which gives “ZHAOYUANREN YUYANXUELUNWENJI” instead of “Zhào Yuánrèn yǔyánxué lùnwénjí,” is particularly inappropriate and painful to look at on a collection of the works of this brilliant linguist. But don’t judge this book by its cover.