Recently, Victor Mair posted an image from Taichung of an apostrophe r representing “Mr.” (Alphabetic “Mr.” and “Mrs. / Ms.” in Chinese)

Here’s a companion image for a Ms. Huang.

Recently, Victor Mair posted an image from Taichung of an apostrophe r representing “Mr.” (Alphabetic “Mr.” and “Mrs. / Ms.” in Chinese)

Here’s a companion image for a Ms. Huang.

To my relief, I saw very little in the way of the orthography-killing cancer that is InTerCaPiTaLiZaTion while I was in Beijing.

The worst offender I spotted was the cover to Qǐyè yǔ xíngzhèng jīguān chángjiàn yìngyòngwén xiězuò dàquán (企业与行政机关常见应用文写作大全 / 企業與行政機關常見應用文寫作大全), which to me just screams out “UGly NightMare”. But at least the word parsing is right, which is more than can be said for many uses of Pinyin in China.

Note that the image is flipped:

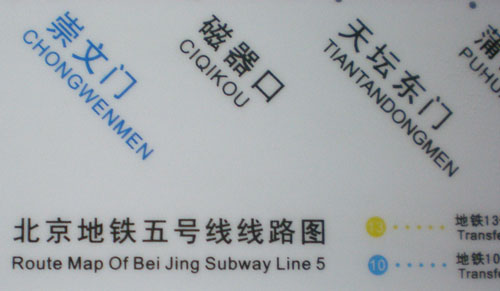

More troubling, because it is on official signage, is the use of intercaps on some station guides above the doors of subway cars.

The capitalization of “Of” demonstrates that the bro-ken and InTerCaPiTaLized “Bei Jing” is probably due more to standard sloppiness than design. At least I certainly hope no one did that on purpose.

Fortunately, that usage isn’t found throughout the subway system, as this photo from a map of another line shows.

Reports of what style is to be found on other Beijing subway lines — especially the newest ones — would be welcome.

And Randy spotted this one:

But that appears to be a one-off, since the Beijing Vikings don’t use that style on their Web site or elsewhere that I noticed.

Typing the letter v to produce ü is pretty standard in most Pinyin-related software — the letter v not being used in Pinyin except for loan words, and the letter ü not being found on traditional qwerty keyboards.

Here’s an official sign not far from Tian’anmen Square in Beijing that provides an example of an unconverted v.

Of course there’s the usual word-parsing trouble as well, which can indeed be tricky in some cases (but not so much that everythingneedstobewrittensolidlikethis).

This should be “Zhīnǚ Qiáo dōng héyán” (织女桥东河沿 / 織女橋東河沿 / Weaver Girl’s Bridge, east bank) or perhaps “Zhinü Qiao Dong Heyan” or “ZHINÜ QIAO DONG HEYAN”.

Some people might not think this is worth categorizing as a problem. My position, however, is that government has an obligation to write things properly on its official signage. (If this were on some ad hoc sign put up privately it would still be interesting but less problematic.) So, if anyone’s OK with the V, would you also be OK with, say, “之釹喬冬和言”?

OTOH, as mistakes go, at least v remains distinct, unlike when ü gets incorrectly written as u, which is so common in Taiwan that I don’t recall ever having seen a ü on official signage. (Pinyin has the following distinct pairs: nü and nu, lü and lu; nüe (rare) and lüe are also used but not nue or lue since the latter two sounds are not used in modern standard Mandarin.

In less than seven hours I’ll be leaving on my first trip to Beijing in fifteen years … and of course I’m not finished packing yet.

While I’m there I’ll of course be doing my usual thing of finding sloppy Pinyin and signage to complain about here. But I’m also hopeful that I’ll be able to pick up some more old tracts in Sin Wenz. Recommendations on where to look would be greatly appreciated.

I’m certainly not expecting the Western media to start writing Tiān’ānmén (天安門/天安门) with tone marks. But its it’s not like the apostrophe is an obscure glyph to be found only in specialist typefaces that dig deep into Unicode, the sort of thing that might require an English form separate from the Pinyin one.

Microsoft Word certainly isn’t helping matters, as it flags the correct form (Tian’anmen) as a misspelling but does not flag the apostrophe-less form (Tiananmen).

Indeed, if you ask the program to help you with the supposedly misspelled “Tian’anmen”, it suggests “Tiananmen”.

So my guess would be that the “Tiananmen” form is the result of a combination of (1) the Cupertino effect, (2) laziness, and (3) people thinking that Tian’anmen “looks funny”.

Ugh.

And as long as I’m on this, it’s not Tian An Men, TianAnMen, Tienanmen, Tianan men, etc., either.

But, no, I don’t expect this will do much good; and if I ever work myself into a case of apostrophe rage it will probably be for other names.

—

further reading:

In recognition of International Talk Like a Beijinger Pirate Day:

further reading:

Sino-Platonic Papers has rereleased for free its fifth volume of reviews, mainly of books about China and its history and languages (11.6 MB PDF).

Even if you have no particular interest in the specific works reviewed, I recommend at least browsing through this and all of the other volumes of reviews from Sino-Platonic Papers, as they often feature Victor Mair at his most direct and entertaining about a wide range of subjects.

Table of Contents:

- Review Article: The Present State and Future Prospects of Pre-Han Text Studies. A review of Michael Loewe, ed., Early Chinese Texts: A Bibliographical Guide. Reviewed by E. Bruce Brooks, University of Massachusetts at Amherst.

N.B.: The following 29 reviews are by the editor of Sino-Platonic Papers.

- Roger T. Ames, Chan Sin-wai, and Mau-sang Ng, eds. Interpreting Culture through Translation: A Festschrift for D. C. Lau.

- Sau Y. Chan. Improvisation in a Ritual Context: The Music of Cantonese Opera.

- CHANG Xizhen. Beijing Tuhua [Pekingese Colloquial].

- CHANG/AIXINJUELUO Yingsheng [AISINGIORO *Yingsheng]. Beijing Tuhua zhong de Manyu [Manchurian in Pekingese Colloquial].

- BAI Gong and JIN Shan. Jing Wei’er: Toushi Beijingren de Yuyan [“Capital Flavor”: A Perspective on the Language of the Pekingese].

- JIA Caizhu, comp. Beijinghua Erhua Cidian [Dictionary of Retroflex Final-r in Pekingese].

- Julia Ching and R. W .L. Guisso, eds. Sages and Sons: Mythology and Archaeology in Ancient China.

- FENG Zhiwei. Xiandai Hanzi he Jisuanji (Modern Chinese Characters and Electronic Computers).

- FENG Zhiwei. Zhongwen Xinxi Chuli yu Hanyu Yanjiu [Chinese Information Processing and Research on Sinitic].

- Andre Gunder Frank. The Centrality of Central Asia.

- HUANG Jungui. Hanzi yu Hanzi Paijian Fangfa [Sinographs and Methods for Ordering and Looking up Sinographs].

- W. J. F. Jenner. The Tyranny of History: The Roots of China’s Crisis.

- Adam T. Kessler. Empires Beyond the Great Wall: The Heritage of Genghis Khan.

- David R. McCraw. Du Fu’s Laments from the South.

- Michael Nylan, tr. and comm. The Canon of Supreme Mystery, by Yang Hsiung.

- R. P. Peerenboom. Law and Morality in Ancient China: The Silk Manuscripts of Huang-Lao.

- Henry G. Schwarz. An Uyghur-English Dictionary.

- Vitaly Shevoroshkin, ed. Dene-Sino-Caucasian Languages.

- Vitaly Shevoroshkin, ed. Nostratic, Dene-Caucasian, Austric and Amerind.

- Laurence G. Thompson, comp. Studies of Chinese Religion: A Comprehensive and Classified Bibliography of Publications in English, French, and German through 1970.

- Laurence G. Thompson, comp. Chinese Religion in Western Languages: A Comprehensive and Classified Bibliography of Publications in English, French, and German through 1980.

- Laurence G. Thompson, comp. Chinese Religion: Publications in Western Languages, 1981 through 1990.

- Aat Vervoorn. Men of the Cliffs and Caves: The Development of the Chinese Eremitic Tradition to the End of the Han Dynasty.

- WANG Jiting, ZHANG Shaoting, and WANG Suorong, comp. Changjian Wenyan Shumianyu [Frequently Encountered Literary Sinitic Expressions in Written Language].

- John Timothy Wixted. Japanese Scholars of China: A Bibliographical Handbook.

- YÜ Lung-yü, ed. Chung-Yin wen-hsüeh kuan-hsi yüan-liu [The Origin and Development of Sino-Indian Literary Relations].

- ZHANG Guangda and RONG Xinjiang. Yutian Shi Congkao [Collected Inquiries on the History of Khotan].

- ZHANG Yongyan, chief ed. Shishuo Xinxu Cidian [A Dictionary of A New Account of Tales of the World].

- Peter H. Rushton. The Jin Ping Mei and the Non-Linear Dimensions of the Traditional Chinese Novel.

- William H. Baxter, A Handbook of Old Chinese Phonology. Reviewed by Paul Rakita Goldin, Harvard University.

- JI Xianlin (aka Hiän-lin Dschi). Dunhuang Tulufan Tuhuoluoyu Yanjiu Daolun [A Guide to Tocharian Language Materials from Dunhuang and Turfan]. Reviewed by XU Wenkan, Hanyu Da Cidian editorial offices in Shanghai.

- GU Zhengmei. Guishuang Fojiao Zhengzhi Chuantong yu Dasheng Fojiao [The Political Tradition of Kushan Buddhism and Mahayana Buddhism]. Reviewed by XU Wenkan, Hanyu Da Cidian editorial offices in Shanghai.

- W. South Coblin, University of Iowa. A Note on the Modern Readings of 土蕃.

- Rejoinder by the Editor.

- Announcement concerning the inauguration of a new series in Sino-Platonic Papers entitled “Bits and Pieces.”

This work also continues the discussion regarding the Chinese characters “土蕃” and Tibet.

This was first published in July 1994 as issue no. 46 of Sino-Platonic Papers.

The most recent rerelease from Sino-Platonic Papers is Dì-yī ge Lādīng zìmǔ de Hànyǔ Pīnyīn Fāng’àn shì zěnyàng chǎnshēng de? (How Was the First Romanized Spelling System for Sinitic Produced? / 第一个拉丁字母的汉语拼音方案是怎样产生的), by YIN Binyong (尹斌庸).

The author should be familiar to regular readers of this site, as he wrote the standard works on Hanyu Pinyin orthography — Chinese Romanization: Pronunciation and Orthography and the Xinhua Pinxie Cidian — as well as Pinyin-to-Chinese Character Computer Conversion Systems and the Realization of Digraphia in China.

The text is in Mandarin in Chinese characters. Here is the introduction.

This is issue no. 50 of Sino-Platonic Papers. It was first published in November 1994.