It’s times like this I especially miss John DeFrancis. How he would have loved this! It’s partially an example of what he dubbed “Singlish” — not Singapore English but Sino-English, the tortured attempt to use Chinese characters to write English. He details this in “The Singlish Affair,” a shaggy dog story that serves as the introduction to his essential work: The Chinese Language: Fact and Fantasy. (And I really do mean essential. If you don’t have this book yet, buy it and read it.)

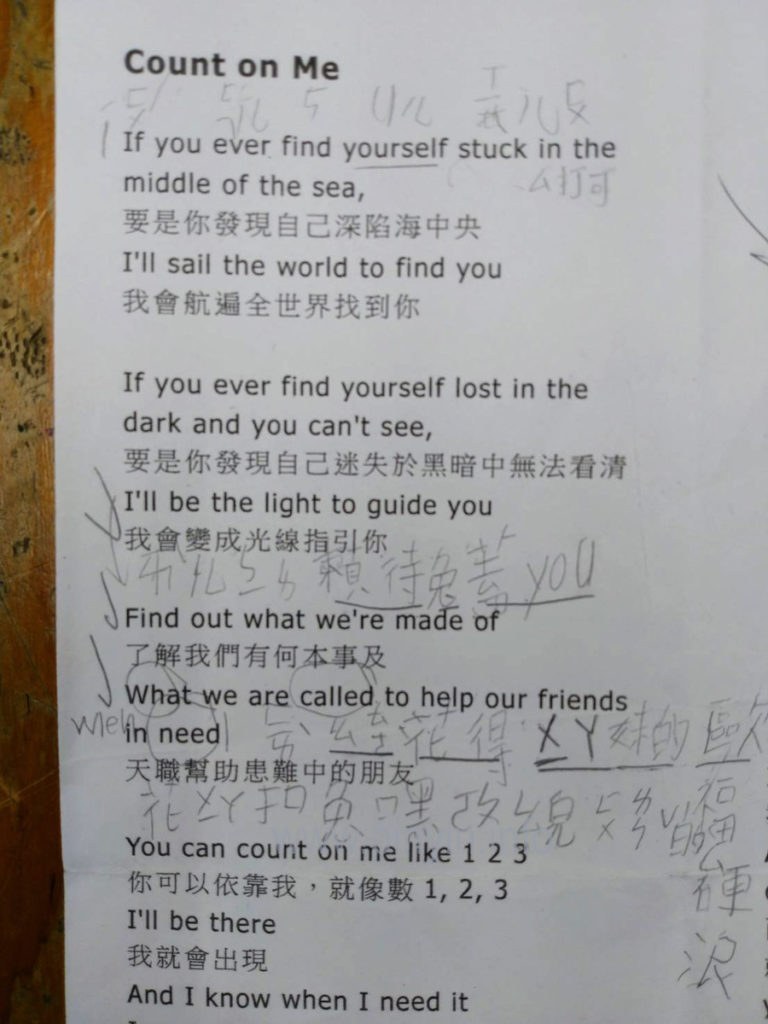

Here are some lyrics from a popular song, “Count on Me,” by Bruno Mars, with a Mandarin translation. The interesting part is that a Taiwanese third-grader has penciled in some phonetic guides for him or herself, using a combination of zhuyin fuhao (aka bopo mofo) (sometimes with tone marks!), English (as a gloss for English! and English pronunciation of some letters and numbers), and Chinese characters (albeit not always correctly written Chinese characters — not that I could do any better myself). Again, this is a Taiwanese third-grader and so is someone unlikely to know Hanyu Pinyin.

“If you ever find yourself stuck”

If |

ㄧˊㄈㄨˊ |

yífú |

| you | ||

| ever | ㄟㄈㄦ | ei-f’er |

find |

5 |

five |

| yourself | Uㄦㄒㄧㄦㄈㄨ | U’er xi’erfu |

stuck |

ㄙ打可 |

s-dake |

“I’ll be the light to guide you.”

I’ll |

ㄞㄦ |

ài’er |

be |

ㄅㄧ |

bi |

| the | ㄌ | l[e] |

light |

賴特* |

laite |

| to | 兔 | tu |

guide |

蓋 |

gai |

you |

you |

you |

“Find out what we’re made of”

Find |

ㄈㄞˋ |

fài |

out |

ㄠㄊㄜ |

ao-t’e |

what |

花得 |

huade |

we’re |

ㄨㄧㄚ |

wi’a |

made |

妹的 |

meide |

of |

歐福 |

oufu |

“When we are called to help our friends in need”

花 |

hua |

|

we |

ㄨㄧ |

wi |

are |

ㄚ |

a |

called |

扣 |

kou |

to |

兔 |

tu |

help |

嘿ㄜㄆ |

hei’e-p[e] |

our |

ㄠㄦ |

ao’er |

friends |

ㄈㄨㄌㄣˇ的ㄙ |

fulen-de-s |

in |

硬 |

ying |

need |

[?] |

[?] |

The standard for alphabetically sorting Hanyu Pinyin is given in the ABC dictionary series edited by John DeFrancis and issued by the University of Hawaii Press.

The standard for alphabetically sorting Hanyu Pinyin is given in the ABC dictionary series edited by John DeFrancis and issued by the University of Hawaii Press.