The following is a guest post by Professor Victor H. Mair. All of the Chinese characters other than those in the scanned image are my own addition.

———–

A friend of ours from Taiwan who keeps a sharp eye out for new cancer medicine for my wife recently sent us the announcement of a new drug, and added the following handwritten note at the end:

| Wǒ | xiāngxìn | hái | huì | yǒu |

| I | believe | still | can | there is/are |

| gèng | hǎod | fāmíng | ||

| more | good | invention |

“I believe that there will be even better inventions.”

Of the eleven Chinese characters in her note, four were simplified: xìn (亻 rén [“man”] on the left and 文 wén [“civil, writing”] on the right), hái (as on the mainland), huì (as on the mainland), and fā (癶 Kangxi radical 105 [bō] on the top as with the original graph, mainland 开 kāi [“open”] on the bottom]).

Here is the text as it would appear in traditional Chinese characters.

The text as it would appear in the PRC’s “simplified” Chinese characters, with the different characters in yellow

Note that, of the four simplified characters in this short note, two are nonstandard according to PRC orthography, which has rén (亻 “man”) on the left and yán (言 “speech”) on the right for xìn (信 “trust; letter”), i.e., the graph is unsimplified on the mainland, and a completely different form for fā (發/发 “emit, occur”). One might have expected that these nonstandard simplified forms would have derived from Japanese forms, since Taiwan has had close cultural ties with Japan during the past century. Yet Japanese orthography does not call for the simplification of xìn at all, and the Japanese simplification of fā, while similar to the simplified form in our friend’s note, has the bottommost strokes curving toward the left and right, whereas our friend has them going straight down. Our friend’s xìn is not an ad hoc invention by her, because I have often seen it used in informal writing, and it is fairly easy to understand how someone might want to substitute the four-stroke component wén (文 “writing”) for the seven-stroke component yán (言 “speech”) when thinking of the meaning “letter, missive” for this character. Our friend’s fā, on the other hand, probably is related to the Japanese form, but further simplified so that the effort to curve the last two strokes left and right is eliminated. In addition, the idea of “open, begin” for the bottom component (开 kāi) was undoubtedly in the mind of the person who devised this simplified form, since it comports well with the fundamental meanings of fā.

What is particularly interesting is that our friend is vocally opposed to the simplification of characters, decrying the mainland communist bandits as destroyers of Chinese civilization, yet she herself uses them regularly and casually, and in her own writing! Indeed, she uses more simplified characters in her writing than are called for by the PRC authorities. The same is true of Chinese writers the world over when they let their hair down and do what comes naturally. The simplification of Chinese characters has been going on for more than two thousand years (see, for example, the many simplified forms in the stele inscriptions of the Six Dynasties period and the profusion of simplified characters in the pinghua [“expository tales”] of the Song period).

I should not neglect to observe that there are also numerous unofficial simplified characters in widespread use on the mainland. For example 午 wǔ (“noon” – four strokes) is a common substitute for 舞 wǔ (“dance” – 14 strokes [!]), 江 jiāng (“[Yangtze] river” – six strokes) frequently replaces 疆 jiāng (“border” – nineteen strokes [!!]) in Xinjiang (the name of the Uyghur region in the far west), and so forth.

What does all of this boil down to? In a nutshell, people are not fools. They do not want to waste their lives writing a dozen* or more strokes for a single syllable when they can convey the same amount of information in four or five strokes. I contend that the natural process of simplification – without artificial (e.g., heavy-handed government) intervention – inevitably results in the development of a syllabary or an alphabet. In fact, this is what happened with Japanese hiragana and katakana, as well as with the nüshu (“women’s script”) of southwestern Hunan. Absent strong government controls and/or elitist models, the same would happen with mainstream hanzi (“sinographs”) in China, and we even see a tendency toward greater emphasis on phoneticization and de-emphasis on semanticization in the official writing system of the PRC. For instance, 云 yún is used both for “cloud” and “say” (ironically, the graph for “cloud” on the oracle bones started out with the simple form, and the “rain” radical 雨 was only added about a thousand years later with the seal form of the graph), while fā (“emit, occur”) and fà (“hair”) share the same graph. This is not, of course, to mention the hundreds of so-called “letter words” (zimuci) that are creeping into Chinese dictionaries, nor the thousands of English words that are invading Chinese speech and writing. But that is a matter for another essay.

==

*The average number of strokes per character is over a dozen for traditional forms and just under a dozen for the complete set of characters that incorporates the official simplified forms. The main reasons why there is not much difference between the two averages are: 1. the vast numbers of characters overall, 2. the relatively few characters that have been officially simplified.

Victor H. Mair

University of Pennsylvania

December 6, 2006

———–

see also Mystery of old simplified Chinese characters?, Pinyin News, October 7, 2005

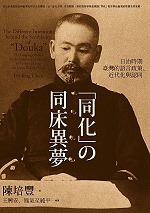

While browsing at Eslite the other day I happened across a new book that sounds interesting:

While browsing at Eslite the other day I happened across a new book that sounds interesting: