The program Key, which offers probably the best support for Hanyu Pinyin of any software and thus deserves praise for this alone, has just come out with an update with even more Pinyin features: Key 5.2 (build: August 21, 2011 — earlier builds of 5.2 do not offer all the latest features).

The program Key, which offers probably the best support for Hanyu Pinyin of any software and thus deserves praise for this alone, has just come out with an update with even more Pinyin features: Key 5.2 (build: August 21, 2011 — earlier builds of 5.2 do not offer all the latest features).

Those of you who already have the program should get the update, as it’s free. But note that if you update from the site, the installer will ask you to uninstall your current version prior to putting in the update, so make sure you have your validation code handy or you’ll end up with no version at all.

(If you don’t already have Key, I recommend that you try it out. A 30-day free trial version can be downloaded from the site.)

Anyway, here’s some of what the latest version offers:

- Hanzi-with-Pinyin horizontal layout gets preserved when copied into MS Word documents (RT setting), as well as in .html and .pdf files created from such documents.

- Pinyin Proofing (PP) assistance: with pinyin text displayed, pressing the PP button on the toolbar will colour the background of ambiguous pinyin passages blue; right-clicking on such a blue-background pinyin passage will display the available options.

- Copy Special: a highlighted Chinese character passage can be copied & pasted automatically in various permutations.

- Improved number-measureword system: it now works with Chinese-character, pinyin and Arabic numerals.

- Showing different tones through coloured characters (Language menu under Preferences).

- Chengyu (fixed four character expression) spacing logic: automatic spacing according to the pinyin standard (Language menu under Preferences).

- Option to show tone sandhi on grey background (Language menu under Preferences).

- Full support of standard pinyin orthography in capitalization and spacing.

- Automatic glossary building.

Some programs, such as Popup Chinese’s “Chinese converter,” will take Chinese characters and then produce pinyin-annotated versions, with the Pinyin appearing on mouseover. Key, however, offers something extra: the ability to produce Hanzi-annotated orthographically correct Pinyin texts (i.e,, the reverse of the above). If you have a text in Key in Chinese characters, all you have to do is go to File --> Export to get Key to save your text in HTML format.

Here’s a sample of what this looks like.

Běn biāozhǔn guīdìngle yòng《 Zhōngwén pīnyīn fāng’àn》 pīnxiě xiàndài Hànyǔ de guīzé。 Nèiróng bāokuò fēncí liánxiě fǎ、 chéngyǔ pīnxiěfǎ、 wàiláicí pīnxiěfǎ、 rénmíng dìmíng pīnxiěfǎ、 biāodiào fǎ、 yíháng guīzé děng。

Basically, this is a “digraphia export” feature — terrific!

If you want something like the above, you do not have to convert the Hanzi to orthographically correct Pinyin first; Key will do it for you automatically. (I hope, though, that they’ll fix those double-width punctuation marks one of these days.)

Let’s say, though, that you want a document with properly word-parsed interlinear Hanzi and Pinyin. Key will do this too. To do this, a input a Hanzi text in Key, then highlight the text (CTRL + A) and choose Format --> Hanzi with Pinyin / Kanji-Kana with Romaji.

In the window that pops up, choose Hanzi with Pinyin / Kanji-kana with Romaji / Hangul with Romanization from the Two-Line Mode section and Show all non-Hanzi symbols in Pinyin line from Options. The results will look something like this:

This can be extremely useful for those authoring teaching materials.

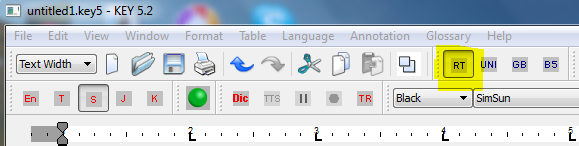

Furthermore, such interlinear texts can be copied and pasted into Word. For the interlinear-formatted copy-and-paste into Word to work properly, Key must be set to rich text format, so before selecting the text you wish to use click on the button labeled RT. (Note yellow-highlighted area in the image below.)

Today’s selection from Yin Binyong’s Xīnhuá Pīnxiě Cídiǎn (《新华拼写词典》 / 《新華拼寫詞典》) deals with how to write Mandarin’s adjectives.

Today’s selection from Yin Binyong’s Xīnhuá Pīnxiě Cídiǎn (《新华拼写词典》 / 《新華拼寫詞典》) deals with how to write Mandarin’s adjectives.