It appears that few things are harder to get rid of than a Taipei City Government official’s bad idea.

Four years ago I noted that city hall was sponsoring a “festival” for beef noodle soup and promoting it to foreigners through a machine-translated Chinglish Web site and the absurd use of the supposedly English “Newrow Mian” for niúròumiàn (牛肉麵/牛肉面).

The city has continued to host the annual event. This year, the city appears to have moved to solve its Chinglish problem by simply failing to provide English translations — though one wonders just where the “international” part comes in without much of anything in English. Thus, useful English is lacking; but fake English like “Newrow Mian” remains.

This has come to the attention of the media. For example, see this video report: Niúròumiàn = New Row Mian? Shì-fǔ zhíyì rěyì.

Táiběi Shìzhèngfǔ jǔbàn niúròumiàn jié, xiànzài yào tuī wǎng guójì, buguò què yǒu yǎnjiān mínzhòng fāxiàn, huódòng hǎibào, bǎ Zhōngwén “niúròumiàn” zhíjiē yīn yìchéng Yīngwén de “New Row Mian,” bùshǎo guówài lǚkè kànle dōu tǎnyán, wánquán bù dǒng shénme yìsi, zhìyí shì-fǔ shìbushì Yīngwén fānyì yòu chūbāo, buguò shì-fǔ chéngqīng, shuōshì wèile xuānchuán “niúròumiàn” de Zhōngwén niànfǎ, ràng tā xiàng shòusī, pīsà yīyàng, ràng quánshìjiè dōu zhāozhe yuánwén niàn.

According to the brief write-up above, some people had noticed that foreigners had no idea what this “new row mian” was or even how to say it, so the municipal authorities explained that this is for the sake of publicizing the Chinese pronunciation of niúròumiàn. City authorities dream that English will take on “new row mian” as a loan term, just like sushi and pizza. (Apparently it’s important to convey to the world the Chinese-ness (with Taiwanese characteristics) of this dish, so “beef noodle soup” — which is what just about everyone in Taiwan calls this when speaking in English — just won’t do.)

Sigh.

Really, this isn’t that difficult. If you want to use the roman alphabet to write a Mandarin term, use Hanyu Pinyin. Although Pinyin will not be helpful in all situations to people who know nothing about the system, neither will anything else. But Hanyu Pinyin stands the best chance of working because it’s the international system for writing Mandarin in romanization. It’s also Taiwan’s official system for writing Mandarin in romanization. And it’s even the Taipei City Government’s official system for writing Mandarin in romanization, which means the city is supposed to use it rather than employing ad hoc bullshit year after year.

Anyway, the festival doesn’t start until November 17, so if you have ever wanted to “beef the world” — and who hasn’t? — now’s the time. (That this is being run by an ad agemcy agency that somehow missed getting its own name right, however, doesn’t inspire confidence.)

If anyone would like to let the city know your thoughts about this, the contact person is Ms. Yè, who can be reached at 1999 ext. 6507, or at 02-2599-2875 ext. 214 or 220. Tell them this concerns the Táiběi Guójì Niúròumiàn Jié.

Further reading:

- 2011 Taipei International New row Mian Festival official site

And for still more reading, see the Taipei City Government’s massive PDF (157 MB!) for the 2008 event. This has lots of English (and Japanese!), which appears not to have been machine translated; but some parts could certaintly use improvement, such as “The regretful beef noodles have been staying in my memory.” Additionally, the romanization system employed is Tongyong Pinyin, rather than Taipei’s official Hanyu Pinyin (e.g., “Rih Pin Shan Si Dao Siao Mian” instead of “Rì Pǐn Shānxī dāoxiāomiàn” and “HONG SHIH FU SIN JHUAN” instead of Hóng Shīfu Xīn Zhuàn).

Of course, it’s not consistent even in its incorrect use of Tongyong. It also contains broken bastardized Wade-Giles (e.g., the “Kuan Tu” MRT station instead of “Guandu”) and the city’s “new row” whenever it gets the chance (e.g., HUANG ZAN NEWROW MIAN FANG instead of Huáng Zàn Niúròumiàn Fáng / 皇贊牛肉麵坊).

Later, all of the stores’ addresses are given in Tongyong Pinyin (e.g., Chongcing, Mincyuan, Jhihnan, Mujha, Singlong, Jhongsiao).

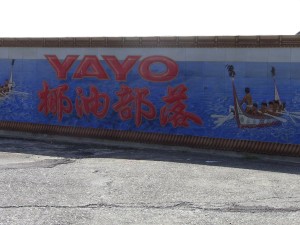

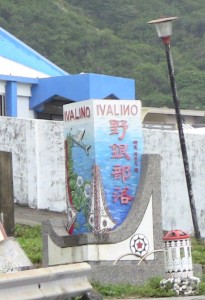

Here are some signs in Taimali Taimali (Tàimálǐ / 太麻里), Taidong County, Taiwan. In all cases of distinctive spellings, they’re in Tongyong Pinyin, even though they should have been replaced by Hanyu Pinyin years ago. When the change to Tongyong Pinyin was implemented, however, signs under national control (e.g., highway signs) were switched relatively quickly throughout the country. This, however, has not been the case with the switch to Hanyu Pinyin, especially in the south.

Here are some signs in Taimali Taimali (Tàimálǐ / 太麻里), Taidong County, Taiwan. In all cases of distinctive spellings, they’re in Tongyong Pinyin, even though they should have been replaced by Hanyu Pinyin years ago. When the change to Tongyong Pinyin was implemented, however, signs under national control (e.g., highway signs) were switched relatively quickly throughout the country. This, however, has not been the case with the switch to Hanyu Pinyin, especially in the south.