There are plenty of ways to type Hanyu Pinyin with tone marks. These usually involve typing the tone number after the vowel in question or entering a series of special keystrokes to produce the tone mark.

But some consider that too much mafan, or perhaps are unsure of which tones are correct. (Heads up, students learning Mandarin! This post will be useful.) So occasionally I’m asked this question:

Is there a way to type in Hanyu Pinyin and have the correct tone marks appear automatically — even without typing tone numbers or pressing additional keys? Oh, and for free too, please.

The answer is a qualified yes.

Google Translate’s Pinyin function has come a long way since its inauspicious beginning about eight years ago. For quite some time it has even offered a way to add tone marks automatically, though few people know of this function, which could still use a great deal of improvement.

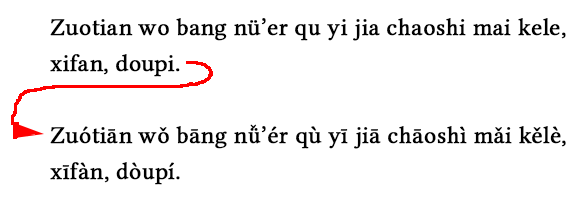

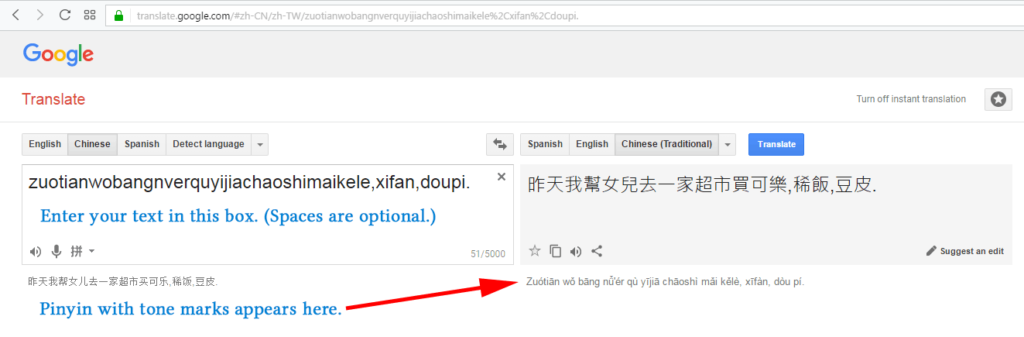

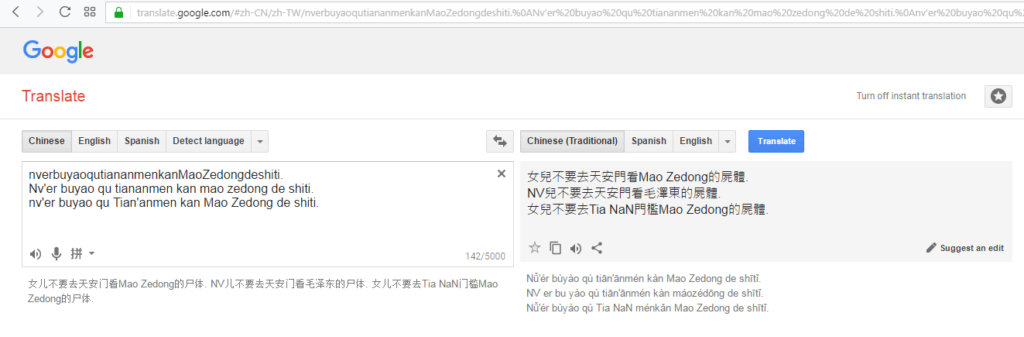

To get Google Translate to produce Pinyin with tone marks as you enter text in toneless Pinyin, first you need to set the system to translate from “Chinese” to “Chinese (Traditional)” or from “Chinese” to “Chinese (Simplified)”.

Enter your text in the box and Pinyin with tone marks will appear below the box on the right.

(Click any image to enlarge it.)

Alas, there are some problems with the system.

A lot of perfectly normal things that are essential to proper writing in Hanyu Pinyin will cause Google Translate to break. So when adding your text, do not use any of the following:

- capital letters

- the letter ü (use “v” instead)

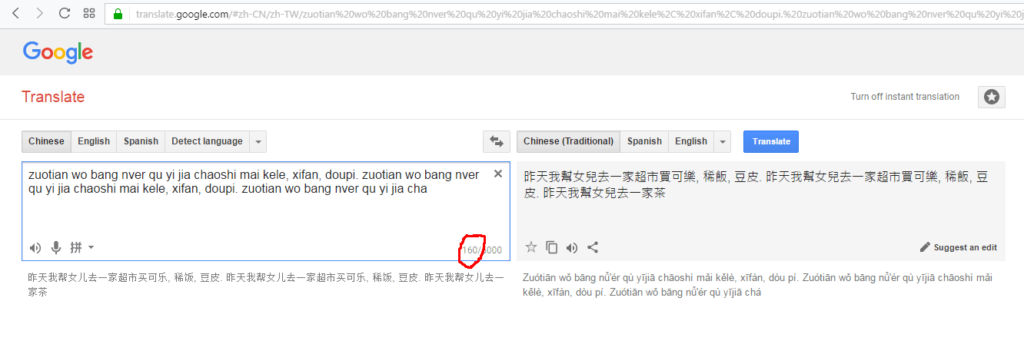

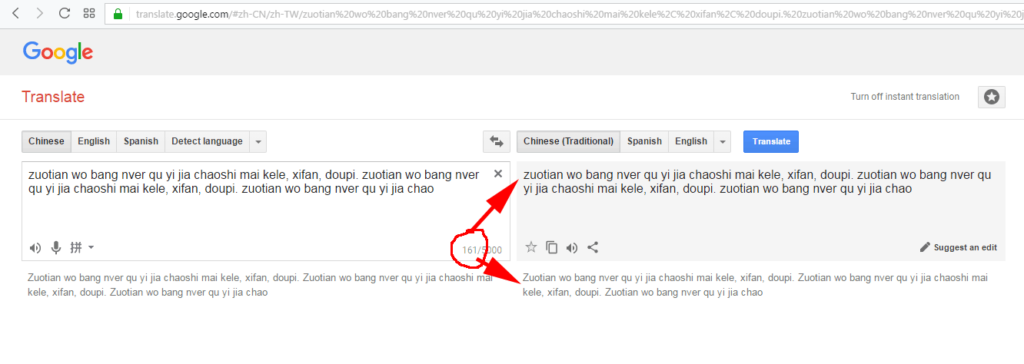

- more than 160 characters (including spaces and punctuation) at a time

Up to 160 characters is fine

But more than 160 characters will break the function that adds tone marks to Pinyin

The following are optional in terms of getting Google Translate to give you good results, though they are not optional in properly written Pinyin:

- apostrophes

- spaces

- punctuation

A second significant problem is that the system doesn’t deal well with proper nouns, failing both word parsing and capitalization, though at least it seems to recognize that proper nouns are units, even if Google Translate doesn’t write them correctly.

So although Google Translate won’t handle everything for you, it can nevertheless be a useful tool for including tone marks in Hanyu Pinyin.