A bill that would make the teaching of Mandarin compulsory in all schools in Panama has passed the first of three readings in the Panamanian National Assembly.

In looking for details on this, I found a document on the Panamanian National Assembly’s Web site from September 5, 2005: Que Establece la Enseñanza Obligatoria del Idioma Mandarín, en los Centros Educativos Oficiales y Particulares del Primer y Segundo Nivel de Enseñanza y Se Dictan Otras Disposiciones (PDF).

If that represents the draft that was passed yesterday, here is a quote that may provide important information:

El Ministerio de Educación establecerá la carga horaria necesaria, que garantice el aprendizaje efectivo del idioma desde los primeros niveles de enseñanza, lo cual implica que el estudiante que culmina el bachillerato pueda comunicarse verbalmente y por escrito en mandarín. (emphasis added)

So this isn’t just for spoken Mandarin. Students who gain a bachillerato would be expected to be able to not only speak but also write Mandarin. (Can someone help clarify just what level a bachillerato represents?)

As much as I would like for more people around the world to learn Mandarin, it’s necessary to be blunt here: If the legislators and educators of Panama expect all of that country’s students to achieve literacy in Mandarin through Chinese characters, they are not only living in a fantasy world but also setting up what will certainly be a monumental and expensive failure. If this means, as it probably does, literacy in Chinese characters, the students of Panama have a whole world of frustration waiting for them.

Certainly some students will succeed. But the percent who do will never make it into double digits. Moreover, requiring Mandarin for everyone is not practical but a massive overestimation of the need for Panamanians to be able to communicate in Mandarin. I do not say that is how things ought to be, just that that is how they are … and how they will remain for many years to come. From a practical point of view, which is what legislators ought to be taking when imposing universal requirements, having a high level of English matters much, much more than having a high level of Mandarin, though certainly programs need to be widely available to provide students with the choice to learn Mandarin.

For another approach to the question of achieving literacy in Mandarin, let’s look at the case of Singapore. The majority of those in the city-state are ethnic Chinese, many of whom are native speakers of various Sinitic languages. There’s no shortage of money for education; and there’s no shortage of Mandarin classes or teachers. Official statistics there state that in the year 2000:

- 82.2 percent of the literate ethnic Chinese population was literate in at least Mandarin

- 0.7 percent of the literate ethnic Indian population was literate in at least Mandarin

- 0.3 percent of the literate ethnic Malay population was literate in at least Mandarin

If nearly 20 percent of Singapore’s literate ethnic Chinese population is not literate in Mandarin, and less than 1 percent of the literate ethnic Malay and Indian populations is literate in Mandarin, what chance does Panama think it has of having this succeed with its own decidedly non-Chinese population?

Note: It’s going to be a little tricky to figure out the details of some of Panama’s plan because references to “China” may well be to Taiwan, which Panama recognizes as the Republic of China. So sometimes “China” will mean China (PRC), and sometimes “China” will mean Taiwan (ROC). Expect confusion in news stories about this.

additional sources:

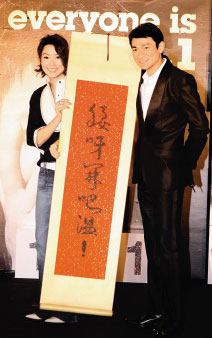

Joel of Danwei has posted about an interesting calligraphy scroll presented to Hong Kong superstar Andy Lau.

Joel of Danwei has posted about an interesting calligraphy scroll presented to Hong Kong superstar Andy Lau.