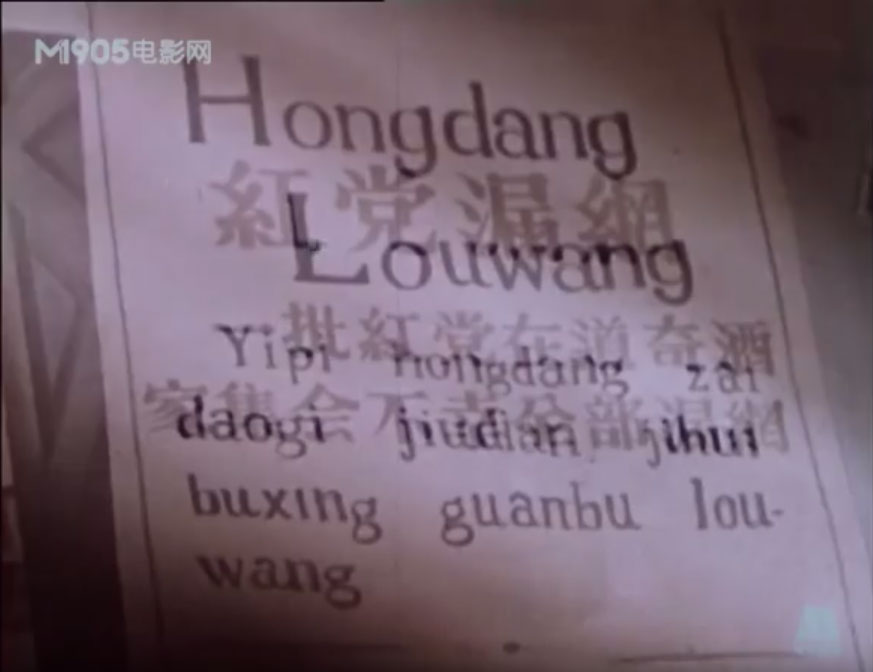

The Shanghai Road Administration Bureau is considering removing Hanyu Pinyin from street signs in the city.

Typically, the bureau’s division chief, Wang Weifeng, seems to be confused about the difference between Pinyin and English. He also justifies the move by claiming that larger Chinese characters would benefit Chinese citizens, ignoring the high number of people in China who are largely illiterate.

“Of course we will keep the English-Chinese traffic signs around some special areas, such as the tourism spots, CBD areas and some transport hubs,” Wang said.

A German newspaper article notes:

Ob sie die Umschrift wortwörtlich „aus dem Verkehr“ zieht, will Schanghai angeblich von einer „Umfrage“ unter „Anwohnern“ abhängig machen, ebenso vom Urteil nicht näher genannter „Experten“. Dies ist eine gängige Formulierung, wenn chinesische Regierungsstellen ihren einsamen Entscheidungen einen basisdemokratischen Anstrich geben wollen.

[Google Translate: Whether they literally “out of circulation” pulls the inscription, Shanghai will supposedly make a “survey” of “residents” depends, as of indeterminate sentence from “experts”. This is a common formulation, when Chinese authorities want to give their lonely decisions a grassroots paint.]

This is a situation all too common in Taiwan as well, such as in Taipei’s misguided move to apply nicknumbering to subway stops. “Experts” — ha!

Shanghai’s survey on Pinyin use and signage is of course in Mandarin only, with no English. The poll ends on August 30 (next week!), so add your views to that soon.

So far, public opinion seems to be largely against removing Hanyu Pinyin from signs. But that doesn’t mean this might not happen anyway. After all: Shanghai has its “experts” on the case. Heh.

If Shanghai really wanted to help the legibility of its signs, it should consider using word parsing even with text in Chinese characters. For example:

- use 陕西 南路, not 陕西南路

- use 斜土 路, not 斜土路

- use 建国 西路, not 建国西路

That would also permit the use of superscript on the generic parts of names (e.g., “南路”) to save space. This could also be done with the Pinyin/English, with the Pinyin in large letters and the English “Rd” etc. in superscript.

Thanks to Michael Cannings for the tip.

sources:

- City road authority considers removing English content from traffic signboards, Shanghai Daily, August 22, 2016

- Schanghai will englischsprachige Straßenschilder entfernen, Frankfurter Allgemeine, August 23, 2016

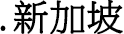

domains compare with the use of .tw domains?

domains compare with the use of .tw domains?  ), so it is omitted here.

), so it is omitted here. and

and  , so those figures are still at zero.

, so those figures are still at zero.  ccTLD, even though the Ma administration, which was in power when Taiwan’s ccTLDs went into effect, officially prefers the more complex form of

ccTLD, even though the Ma administration, which was in power when Taiwan’s ccTLDs went into effect, officially prefers the more complex form of  .

.