Recently, Victor Mair posted an image from Taichung of an apostrophe r representing “Mr.” (Alphabetic “Mr.” and “Mrs. / Ms.” in Chinese)

Here’s a companion image for a Ms. Huang.

Recently, Victor Mair posted an image from Taichung of an apostrophe r representing “Mr.” (Alphabetic “Mr.” and “Mrs. / Ms.” in Chinese)

Here’s a companion image for a Ms. Huang.

The following is a guest post by Victor H. Mair.

=====

How do we learn languages, after all? By following rules, whether hard-wired or learned? Or by acquiring and absorbing principles and patterns through massive amounts of repetitions?

“AI is changing scientists’ understanding of language learning — and raising questions about innate grammar,” a stimulating new article by Morten Christiansen and Pablo Contreras Kallens that first appeared in The Conversation (10/19/2022) and later in Ars Technica and elsewhere, begins thus:

Unlike the carefully scripted dialogue found in most books and movies, the language of everyday interaction tends to be messy and incomplete, full of false starts, interruptions and people talking over each other. From casual conversations between friends, to bickering between siblings, to formal discussions in a boardroom, authentic conversation is chaotic. It seems miraculous that anyone can learn language at all given the haphazard nature of the linguistic experience.

I must say that I am in profound agreement with this scenario. In many university and college departments, which consist entirely of learned professors, you’d think that discussions and deliberations would be governed by regulations and rationality. Such, however, is not the case. Instead, people constantly talk over and past each other, barely listening to what their colleagues are saying. They interrupt one another and engage in aggressive behavior, or erupt in mindless laughter over who knows what. I’m not saying that all the members of these departments are like this nor that all departments are like this, but far too many do converse in this fashion. The individuals who are more sedate and civilized tend to remain silent for hours on end because, as the saying goes, they can’t get a word in edgewise. It’s a wonder that departments can accomplish anything.

For this reason, many language scientists – including Noam Chomsky, a founder of modern linguistics – believe that language learners require a kind of glue to rein in the unruly nature of everyday language. And that glue is grammar: a system of rules for generating grammatical sentences.

Everybody knows these things — or knew them decades ago — but now they are indubitably passé.

Children must have a grammar template wired into their brains to help them overcome the limitations of their language experience – or so the thinking goes.

This template, for example, might contain a “super-rule” that dictates how new pieces are added to existing phrases. Children then only need to learn whether their native language is one, like English, where the verb goes before the object (as in “I eat sushi”), or one like Japanese, where the verb goes after the object (in Japanese, the same sentence is structured as “I sushi eat”).

But new insights into language learning are coming from an unlikely source: artificial intelligence. A new breed of large AI language models can write newspaper articles, poetry and computer code and answer questions truthfully after being exposed to vast amounts of language input. And even more astonishingly, they all do it without the help of grammar.

Now, however, the authors make an astonishing claim. They assert that AI language models produce language that is grammatically correct, but they do so without a grammar!

Even if their choice of words is sometimes strange, nonsensical or contains racist, sexist and other harmful biases, one thing is very clear: the overwhelming majority of the output of these AI language models is grammatically correct. And yet, there are no grammar templates or rules hardwired into them – they rely on linguistic experience alone, messy as it may be.

GPT-3, arguably the most well-known of these models, is a gigantic deep-learning neural network with 175 billion parameters. It was trained to predict the next word in a sentence given what came before across hundreds of billions of words from the internet, books and Wikipedia. When it made a wrong prediction, its parameters were adjusted using an automatic learning algorithm.

Remarkably, GPT-3 can generate believable text reacting to prompts such as “A summary of the last ‘Fast and Furious’ movie is…” or “Write a poem in the style of Emily Dickinson.” Moreover, GPT-3 can respond to SAT level analogies, reading comprehension questions and even solve simple arithmetic problems – all from learning how to predict the next word.

The authors delve more deeply into comparisons of AI models and human brains, not without raising some significant problems:

A possible concern is that these new AI language models are fed a lot of input: GPT-3 was trained on linguistic experience equivalent to 20,000 human years. But a preliminary study that has not yet been peer-reviewed found that GPT-2 [a “little brother” of GPT-3] can still model human next-word predictions and brain activations even when trained on just 100 million words. That’s well within the amount of linguistic input that an average child might hear during the first 10 years of life.

In conclusion, Christiansen and Kallens call for a rethinking of language learning:

“Children should be seen, not heard” goes the old saying, but the latest AI language models suggest that nothing could be further from the truth. Instead, children need to be engaged in the back-and-forth of conversation as much as possible to help them develop their language skills. Linguistic experience – not grammar – is key to becoming a competent language user.

By all means, talk at the table, but respectfully, and not too loudly.

Selected readings

[h.t. Michael Carr]

Commonwealth Magazine (Tiānxià zázhì) recently interviewed me for a Mandarin-language piece related to the signage on Taipei’s MRT system.

As anyone who has looked at Pinyin News more than a couple of times over the years should be able to guess, I had a lot to say about that — most of which understandably didn’t make it into the article. For example, I recall making liberal use of the word “bèn” (“stupid”) to describe the situation and the city’s approach. But the reporter — Yen Pei-hua (Yán Pèihuá / 嚴珮華), who is perhaps Taiwan’s top business journalist — diplomatically omitted that.

Since the article discusses the nicknumbering system Taipei is determined to implement “for the foreigners,” even though most foreigners are at best indifferent to this, but doesn’t include my remarks on it, I’ll refer you to my post on this from last year: Taipei MRT moves to adopt nicknumbering system. Back then, though, I didn’t know the staggering amount of money the city is going to spend on screwing up the MRT system’s signs: NT$300 million (about US$10 million)! The main reason given for this is the sports event Taipei will host next summer. That’s supposed to last for about ten days, which would put the cost for the signs alone at about US$1 million per day.

On the other hand, the city does not plan to fix the real problems with the Taipei MRT’s station names, specifically the lack of apostrophes in what should be written Qili’an (not Qilian), Da’an (not Daan) (twice!), Jing’an (not Jingan), and Yong’an (not Yongan) — in Chinese characters: 唭哩岸, 大安, 景安, and 永安, respectively. And then there’s the problem of wordy English names.

Well, take a look and comment — here, or better still, on the Facebook page. (Links below.) I’m grateful to Ms. Yen and Commonwealth for discussing the issue.

References:

Victor Mair’s terrific essay “Danger + Opportunity ≠ Crisis: How a misunderstanding about Chinese characters has led many astray,” which was written for this site, is featured this week in the Wall Street Journal‘s Notable & Quotable section.

Mair has done more than anyone else to help drive a stake through the heart of this myth. I’m glad the WSJ is helping spread the word.

source: “Notable & Quotable: Lost in Mistranslation“, Wall Street Journal, February 25, 2016

Late last week, Victor Mair — with some assistance from Matt Anderson, David Moser, me, and others — wrote in “Lobsters”: a perplexing stop motion film about a short 1959 film from China that gives some Pinyin. In some cases, the Pinyin is presented for a second and then is quickly dissolved into Chinese characters. Since Victor’s post supplies only the text, I thought that I’d supplement that here with images from the film.

See the original post for translations and discussion.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HKYMO73hLRY

The film often shows a newspaper. The headline (at 7:57) reads (or rather should read, since the first word is misspelled):

QICHE GUPIAO MENGDIE

DAPI LONGXIA ZHIXIAO

But since the image above doesn’t show the name of the paper, I’m also offering this rotated and cropped photo, that allows us to see that this is the “JIN YUAN DIGUO RI-BAO”

Elsewhere, there are again some g’s for q’s. For the first example of text dissolving from Pinyin to Chinese characters (at 2:11), I’m offering screenshots of the text in Pinyin, the text during the dissolve, and the text in Chinese characters. Later I’ll give just the Pinyin and Chinese characters.

Hongdang Louwang

Yipi hongdang zai daogi [sic] jiudian jihui buxing guanbu [sic] louwang

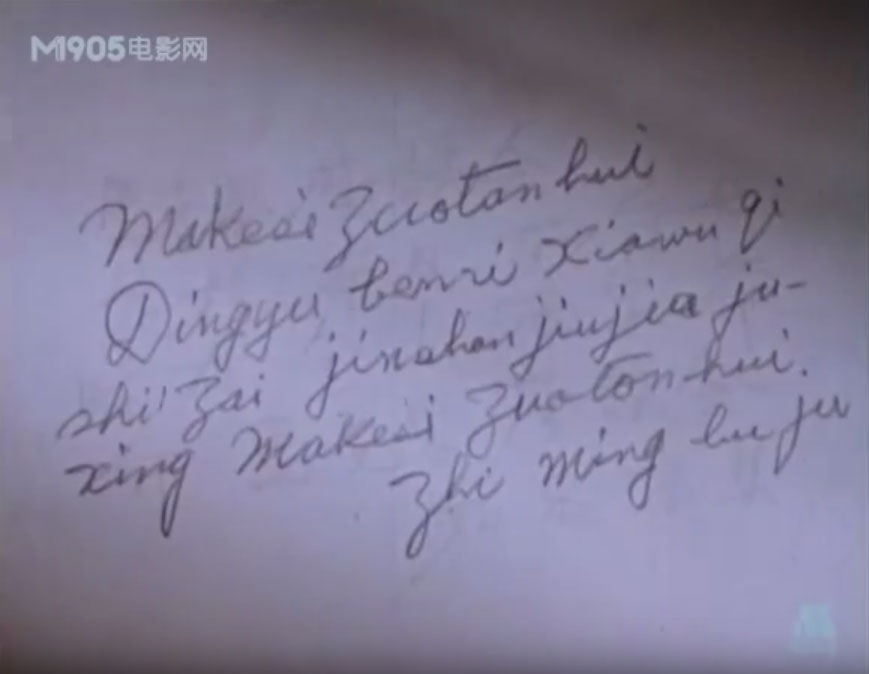

Soon thereafter (at 2:44), we get a handwritten note.

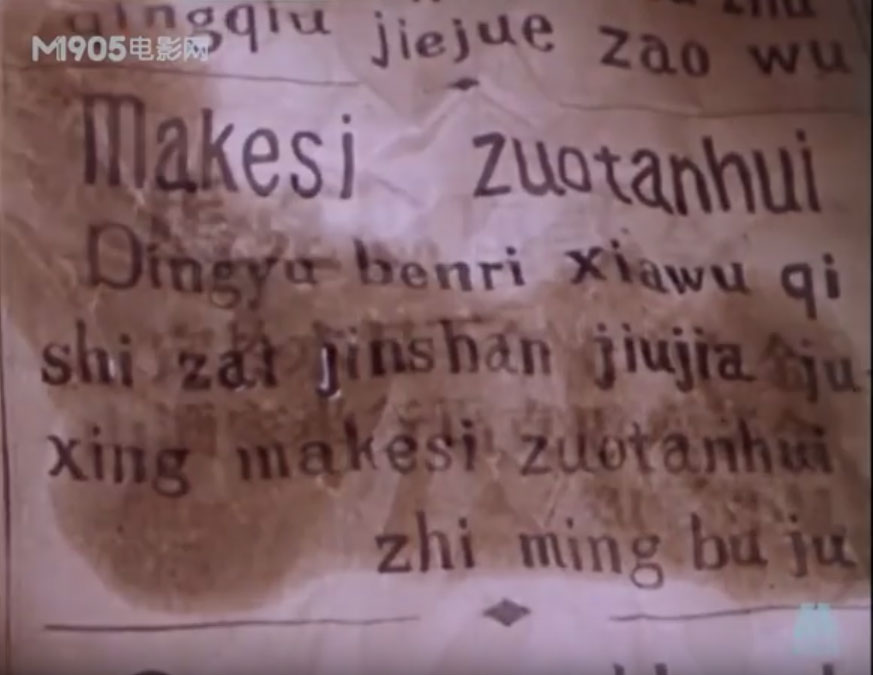

At 3:39 we’re shown the printed notice in the newspaper of the above text.

A brief glance at the newspaper at 3:23 gives us FA CHOU, which is probably referring to the stink the bad lobsters are giving off.

Here a man is carrying a copy of Zibenlun (Das Kapital), by Makesi (Marx).

Actually, it’s not really Das Kapital, just the cover of the book; inside is a stack of decadent Western material. “MEI NE” is probably supposed to be “MEINÜ” (beautiful women).

I imagine that, in the PRC of 1959, the artists for this film must have inwardly rejoiced at the chance to draw something like that for a change, and that is also why there’s a nude on the wall in one scene.

A couple of days ago the New York Times ran a small piece, “How Emojis Find Their Way to Phones.” It contains the sort of nonsense about Chinese characters and language that often sets me off.

Fortunately, Victor Mair quickly posted something on this. J. Marshall Unger (Ideogram: Chinese Characters and the Myth of Disembodied Meaning, The Fifth Generation Fallacy, and Literacy and Script Reform in Occupation Japan) and S. Robert Ramsey (The Languages of China) quickly followed. But since those are in the comments to a Language Log post and thus may not be seen as much as they should be, I thought I’d link to them here.

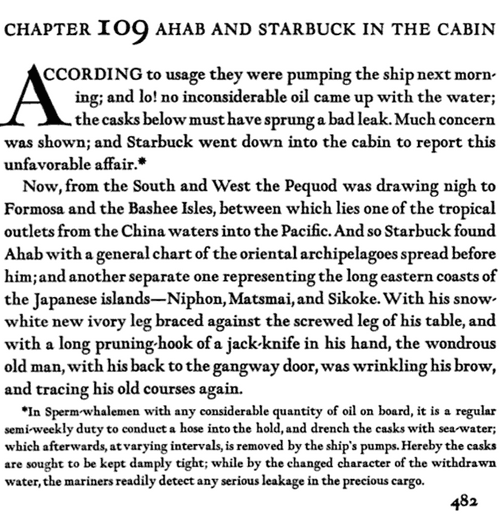

The Language Log post itself is on Emoji Dick, which is billed as a translation of Moby Dick into emoji. As long as I’m writing, I might as well offer up a sample for you. See if you can determine the original English.

![]()

Did you try “Call me Ishmael”? Sorry. That’s not it. But if you guessed that I would choose the passage from Moby Dick that mentions Taiwan, give yourself bonus points.

Here’s what the above emoji supposedly translate:

Hereby the casks are sought to be kept damply tight; while by the changed character of the withdrawn water, the mariners readily detect any serious leakage in the precious cargo.

Now, from the South and West the Pequod was drawing nigh to Formosa and the Bashee Isles, between which lies one of the tropical outlets from the China waters into the Pacific.

Ah, of course. It’s all so clear now.

The next time you hear someone use “pictorial language,” “ideographs,” or the like in all seriousness, perhaps ask them for their own English translation of the above string of images.

Actually, Emoji Dick screwed this up some, as part belongs to the main text and part to a footnote.

The ninth issue of Xin Tang is now available here on Pinyin.info. The journal, which was published in the 1980s, is in and about romanization. By this point in its publication most everything in it was written in Hanyu Pinyin (as opposed to Gwoyeu Romatzyh or another system). Xin Tang is interesting not just as a forum in which one can read original content in Pinyin. It’s also important for the history of Pinyin itself. Over the course of its nearly decade-long run, one can see its authors (including many top people in romanization) working out Pinyin as a real script.

Xin Tang no. 9 (December 1988)

Here’s an English version of the table of contents. Note that the articles themselves are, for the most part, in Mandarin.

Last week, on the same day President Ma Ying-jeou accepted the resignation of a minister who made some drunken lewd remarks at a wěiyá (year-end office party), Ma was joking to the media about blow jobs.

Classy.

But it was all for a good cause, of course. You see, the Mandarin expression chuī lǎba, when not referring to the literal playing of a trumpet, is usually taken in Taiwan to refer to a blow job. But in China, Ma explained, chuī lǎba means the same thing as the idiom pāi mǎpì (pat/kiss the horse’s ass — i.e., flatter). And now that we have the handy-dandy Zhōnghuá Yǔwén Zhīshikù (Chinese Language Database), which Ma was announcing, we can look up how Mandarin differs in Taiwan and China, and thus not get tripped up by such misunderstandings. Or at least that’s supposed to be the idea.

The database, which is the result of cross-strait cooperation, can be accessed via two sites: one in Taiwan, the other in China.

It’s clear that a lot of money has been spent on this. For example, many entries are accompanied by well-documented, precise explanations by distinguished lexicographers. Ha! Just kidding! Many entries are really accompanied by videos — some two hundred of them — of cutesy puppets gabbing about cross-strait differences in Mandarin expressions. But if there’s a video in there of the panda in the skirt explaining to the sheep in the vest that a useful skill for getting ahead in Chinese society is chuī lǎba, I haven’t found it yet. Will NMA will take up the challenge?

Much of the site emphasizes not so much language as Chinese characters. For example, another expensively produced video feeds the ideographic myth by showing off obscure Hanzi, such as the one for chěng.

WARNING: The screenshot below links to a video that contains scenes with intense wawa-ing and thus may not be suitable for anyone who thinks it’s not really cute for grown women to try to sound like they’re only thwee-and-a-half years old.

In a welcome bit of synchronicity, Victor Mair posted on Language Log earlier the same week on the unpredictability of Chinese character formation and pronunciation, briefly discussing just such patterns of duplication, triplication, etc.

Mair notes:

Most of these characters are of relatively low frequency and, except for a few of them, neither their meanings nor their pronunciations are known by persons of average literacy.

Many more such characters consisting or two, three, or four repetitions of the same character exist, and their sounds and meanings are in most cases equally or more opaque.

The Hanzi for chěng (which looks like 馬馬馬 run together as one character) in the video above is sufficiently obscure that it likely won’t be shown correctly in many browsers on most systems when written in real text: 𩧢. But never fear: It’s already in Unicode and so should be appearing one of these years in a massively bloated system font.

Further reinforcing the impression that the focus is on Chinese characters, Liú Zhàoxuán, who is the head of the association in charge of the project on the Taiwan side, equated traditional Chinese characters with Chinese culture itself and declared that getting the masses in China to recognize them is an important mission. (Liu really needs to read Lü Shuxiang’s “Comparing Chinese Characters and a Chinese Spelling Script — an evening conversation on the reform of Chinese characters.”)

Then he went on about how Chinese characters are a great system because, supposedly, they have a one-to-one correspondence with language that other scripts cannot match and people can know what they mean by looking at them (!) and that they therefore have a high degree of artistic quality (gāodù de yìshùxìng). Basically, the person in charge of this project seems to have a bad case of the Like Wow syndrome, which is not a reassuring trait for someone in charge of producing a dictionary.

The same cooperation that built the Web sites led to a new book, Liǎng’àn Měirì Yī Cí (《兩岸每日一詞》 / Roughly: Cross-Strait Term-a-Day Book), which was also touted at the press conference.

The book contains Hanyu Pinyin, as well as zhuyin fuhao. But, alas, the book makes the Pinyin look ugly and fails completely at the first rule of Pinyin: use word parsing. (In the online images from the book, such as the one below, all of the words are se pa ra ted in to syl la bles.)

The Web site also has ugly Pinyin, with the CSS file for the Taiwan site calling for Pinyin to be shown in SimSun, which is one of the fonts it’s better not to use for Pinyin. But the word parsing on the Web site is at least not always wrong. Here are a few examples.

Still, my general impression from this is that we should not expect the forthcoming cross-strait dictionary to be very good.

Further reading: