Names of people in Taiwan have had a default format for many decades. For example:

- Lee Teng-hui

- Chen Shui-bian

- Ma Ying-jeou

- Tsai Ing-wen

The similarity, however, is not in use of a single romanization system. None of those names share the exact same romanization system or combination of systems:

- Lee (common phonetic spelling) Teng-hui (Wade-Giles)

- Chen Shui-bian (Hanyu Pinyin!)

- Ma Ying (Wade-Giles, probably) jeou (Gwoyeu Romatzyh)

- Tsai (bastardized Wade-Giles) Ing (ad hoc spelling) wen (Wade-Giles, probably)

But, different as those people are and different as the romanization systems used are, all of those names share an obvious pattern that marks them as belonging to someone in Taiwan: the hyphen joining the two parts of the given name, and the use of a lowercase letter for the second part of the given name.

Around twenty years ago, during Taiwan’s romanization wars (when President Chen wanted to impose Tongyong Pinyin upon Taiwan and a great many foreigners and others reacted with dismay and disgust), a popular claim of the Tongyong supporters was, “If Taiwanese use Hanyu Pinyin for their names, no one will be able to tell Taiwanese from Chinese anymore.”

This, however, was, like most claims of Tongyong supporters, not true. (It was also pretty funny, given that the most powerful supporter of Tongyong Pinyin was Chen Shui-bian, whose name is unambiguously Hanyu Pinyin but whom no even remotely knowledgeable person would ever mistake for someone from the PRC). The style used for names in China is “Familyname Givenname” (no hyphen). All Taiwanese have to do to keep their names distinct is to preserve the hyphen (assuming they even desire to use Hanyu Pinyin, which is not now nor has ever been required here for personal names).

This is easy:

- PRC vs. TAIWAN

- Li Denghui vs. Li Deng-hui

- Chen Shuibian vs. Chen Shui-bian

- Ma Yingjiu vs. Ma Ying-jiu

- Cai Yingwen vs. Cai Ying-wen

But a few years back the government of Taiwan announced that it would be issuing a new style of the national ID card. Based on the mock-ups the government supplied, these cards would include romanization (yea!), but romanization in a very un-Taiwanese style (argh!).

What’s especially odd, though, is that the romanization clearly follows the style of names in Singapore, not Taiwan.

Here, for example, are the names of some prominent Singaporeans:

- Lee Kuan Yew

- Goh Chok Tong

- Lee Hsien Loong

Again, the standard pattern for Singaporean names is easy to discern … and clearly distinct from the standard pattern of names in Taiwan.

Why is the government doing this? Switching from Taiwan style to Singapore style makes no sense — not historically, not practically (separating given names makes it harder to tell what’s the family name and what’s the given name), and not politically.

And why on earth is “林” being romanized on the card as “LING” rather than as “LIN”, and “森” as “SHENG” rather than as “SEN”? Typos in not one but both of the only two personal names given do not inspire confidence.

Her name should be given, in descending order of preference, as

CHEN Xiao-lin

Chen Xiao-lin

or CHEN XIAO-LIN

not CHEN XIAO LING.

I had been hopeful that the cards and their new style had simply been killed off and so the problem had been effectively eliminated years ago. But according to a recent Taiwan News story, the “eID scheme is halted but not scrapped.” So this nonsense might still happen.

The only good thing I have to say about the Pinyin on the mock-ups (other than its existence) is that it is at least not prohibitively tiny, which is a common problem.

By the way, hyphens can appear in some names in Hanyu Pinyin — but not in the way many people may first guess. Two-syllable family names are written solid, not hyphenated (e.g., Ouyang and Sima, not Ou-yang and Si-ma). Rather, hyphens exist in standard names in China in Hanyu Pinyin in cases where someone decides to adopt her spouse’s name but also preserve her maiden name. So, if a Ms. Wang marries a Mr. Li but wants to have both names, she becomes Ms. Wang-Li (or Ms. Li-Wang).

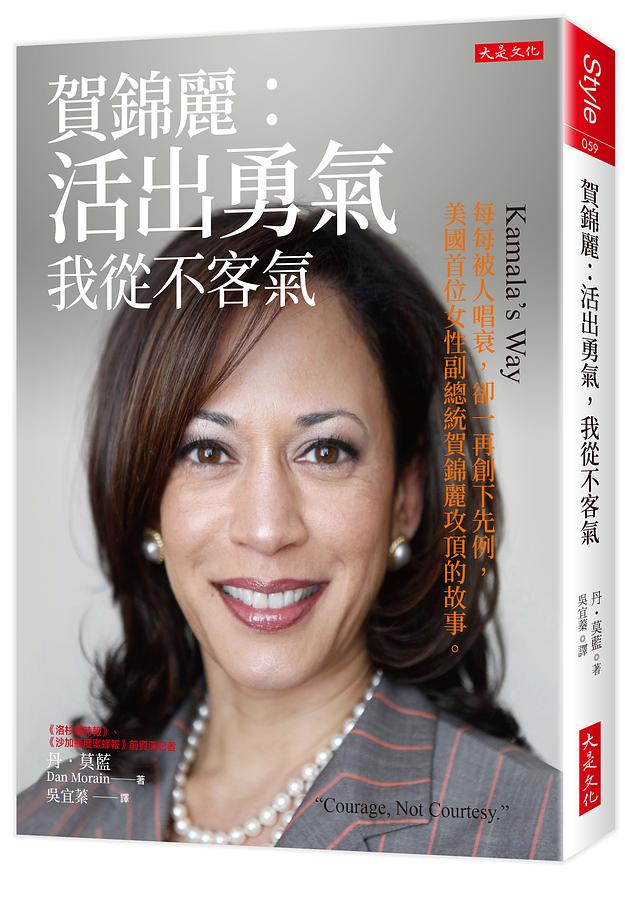

Here’s what Taiwan’s national ID cards look like presently:

Further reading:

Contractor seeks NT$526 million in compensation for Taiwan’s halted digital ID plan. Taiwan News, May 8, 2023.