Recently, Victor Mair posted an image from Taichung of an apostrophe r representing “Mr.” (Alphabetic “Mr.” and “Mrs. / Ms.” in Chinese)

Here’s a companion image for a Ms. Huang.

Recently, Victor Mair posted an image from Taichung of an apostrophe r representing “Mr.” (Alphabetic “Mr.” and “Mrs. / Ms.” in Chinese)

Here’s a companion image for a Ms. Huang.

Earlier this evening I went to a rally for Hsiao Bi-khim, the Democratic Progressive Party’s candidate for vice president of Taiwan.

Most of the speakers at the rally, including Hsiao, spoke in Taiwanese, or in fluent code switching between Taiwanese and Mandarin. Hsiao, who spoke mainly in Taiwanese with some Mandarin mixed in, is more of a policy wonk than a tub-thumper. Although she struck me as better at campaign rallies than Tsai Ing-wen was earlier in her career, her remarks did include coverage of some things, important though they are, that aren’t typically used to boost crowd enthusiasm, such as working toward a tax treaty with the United States. But I was happy to hear her mention the importance of learning not just English but also keeping Taiwanese (Hoklo) and the languages of Taiwan’s indigenous peoples alive.

Part of the rally was in support of this, with a children’s group organized to help promote the speaking of Taiwanese among young people performing a skit in Taiwanese and then a rousing version of “Jingle Bells” in that language.

Hsiao is also a native speaker of English. I heard her speak (in English) about ten years ago and was impressed with her intelligence and thoughtfulness.

If you’re in Taiwan, make a trip to your local 50% Fifty Percent Píngjià Shíshàng (50% FIFTY PERCENT 平价时尚) (50 percent bargain-price fashion) and pick up one of their shirts of various Taiwanese foods, each of which is labeled in romanized Taiwanese. (Place name hashtags (e.g., #Yilan) are not included on the shirts.)

The only problem is that you may want to carry a magnifying glass with you, because the images and letters are tiny. (C’mon, people! When you want people to read something, size matters.)

This is the one I picked for myself: tshang-iû-piánn (in Mandarin: cōngyóubǐng / 蔥油餅 / 葱油饼). Those scallion pancakes are wonderful.

More images on the 50% Fifty Percent Facebook page.

Penang, Malaysia, is reportedly moving to adopt the Penang dialect of the Hokkien language as a thing of “nonmaterial cultural heritage” (fēi wùzhì wénhuà yíchǎn / 非物质文化遗产).

In Taiwan, Hokkien is also known as “Taiwanese” and “Hoklo.”

The chairman of the Penang Tourism and Creative Economy Affairs Committee said that to preserve Hokkien in Penang, the government there would support a “Speak Hokkien” campaign and allocate funds to NGOs and other groups for activities promoting Hokkien. He also hopes organizations will host competitions not only in Pinyin(!) but also in speaking topolects.

Topolects are an important part of the legacy of Chinese culture, he said.

为传承说方言,确保槟城福建话得以保存和广泛使用,槟政府除了支持社团组织举办“讲福建话”运动,也拨款给乔治市世界遗产机构和非政府组织开展宣传福建话活动。

他希望更多华社组织团体,除了办汉语课程或拼音比赛,也可举办说方言比赛,让民众发现说方言之美与意义,达到Z世代也可说一口流利方言与汉语,毕竟方言也是中华文化与遗产重要部分。

Other Sinitic topolects (fangyan) could also be considered for nonmaterial cultural heritage status, he said.

Whether this really happens, and whether it will be enough to make a difference, remains to be seen. But at least it looks like someone influential in Penang is working hard to move things in the right direction.

Sources:

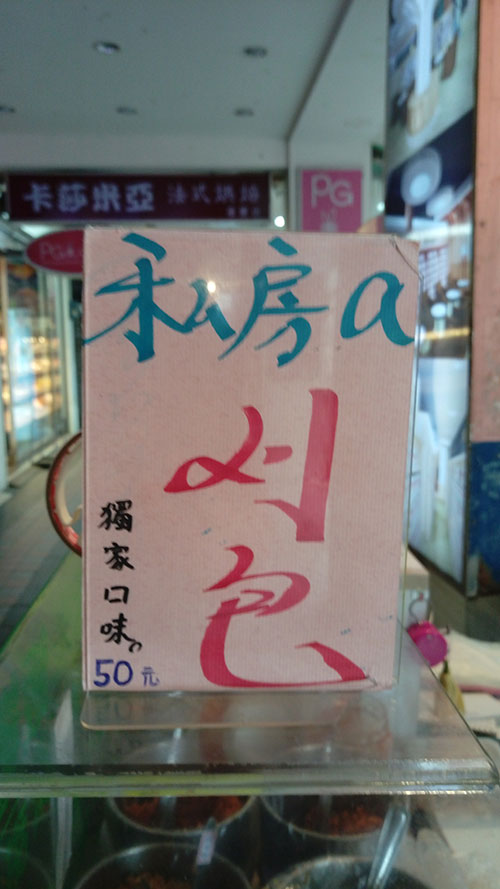

Today I’d like to talk about a sign at a stand that sells guabao, a quintessential Taiwanese snack.

I took my own photo, but it didn’t make the guabao look particularly appetizing, so I’m using a public-domain image instead so you can see what one looks like if you don’t already know. But when I buy one I have them leave off the cilantro/xiāngcài. I hate that stuff.

Here’s the sign.

獨家口味

50元

(NT$50 is about US$1.50.)

The sign uses some Taiwanese, specifically “a刈包.” If the whole thing were in romanized Taiwanese, it would be

To̍k-ka kháu-bī

50 îⁿ

But parts of that are unidiomatic, as Taiwanese expert Michael Cannings informs me. (Alas, my Taiwanese sucks.) So this is a sign in both Taiwanese and Mandarin, which isn’t particularly surprising given that guabao is a Taiwanese food but most people in northern Taiwan use Mandarin most of the time. (I’m using the spelling “guabao” rather than “koah-pau” in most of this post because this is a Pinyin site.)

Something about this sign did surprise me a lot. Can you guess?

What seems to me most distinctive about this sign is that the Roman letter appears in lowercase rather than as “A”.

A single letter being used to represent a Sinitic morpheme in a text otherwise in Chinese characters is almost always written in upper case, e.g., A菜, 宮保G丁, K書. (Oh, that reminds me: I really need to answer that e-mail message about K. Sorry, Steven.)

In other words, if a sign is going to have the Roman letter “a” stand in for the Taiwanese possessive particle (the equivalent of Mandarin’s de/的), I would expect in this particular case for the sign to have “私房A” rather than “私房a”. I’m pleased by the use of lowercase; capital letters should be mainly for proper nouns and the beginnings of sentences.

It’s probably a one-off. But just in case I’ll be on the lookout to see if there’s a trend toward greater use of lowercase.

The text also presents a challenge: How should this be written in Pinyin? The last part (獨家口味 / 50元) is easy, because it’s just straight modern standard Mandarin:

But what to do with this?

Probably this:

The Oxford English Dictionary has just added some new entries, including several from Sinitic languages.

A lot of these come by way of Singapore and so reflect the Hokkien language. For example, among the new entries is “ang pow,” which is Hokkien’s equivalent of Mandarin’s “hongbao,” which also made the list.

A few of the entries, however, come from Mandarin, for example two common interjections for surprise. Oddly, though, the OED uses “aiyoh” and “aiyah” instead of their proper Pinyin spellings of “aiyo” and “aiya.”

“Ah,” you say, “but maybe the aiyoh and aiyah spellings are more common in English.”

Nope.

Even in Singapore domains (.sg), the Pinyin spellings are more common than those the OED calls for. As the tables below show, in every instance the Pinyin spellings are also more common in Hong Kong, China, and Taiwan. Throughout the world, the Pinyin spellings are more common — the vast majority of the time by a factor of at least two.

Google search results for “aiyo” (Pinyin) and “aiyoh” (spelling used in the OED)

| aiyo | aiyoh | |

|---|---|---|

| .sg | 12,200 | 5,680 |

| .hk | 2,570 | 187 |

| .cn | 6,040 | 984 |

| .tw | 4,690 | 196 |

| all domains | 1,250,000 | 137,000 |

| all domains + “chinese” | 97,700 | 77,100 |

| all domains + “mandarin” | 51,800 | 14,100 |

Google search results for “aiya” (Pinyin) and “aiyah” (spelling used in the OED)

| aiya | aiyah | |

|---|---|---|

| .sg | 17,600 | 8,310 |

| .hk | 6,400 | 2,360 |

| .cn | 13,200 | 1,860 |

| .tw | 5,910 | 1,710 |

| all domains | 3,370,000 | 332,000 |

| all domains + “chinese” | 238,000 | 63,200 |

| all domains + “mandarin” | 36,500 | 22,800 |

Searching Google Books also reveals that the Pinyin forms are more common.

In short, I do not see any good reason for the OED to have adopted ad hoc spellings rather than the Pinyin standard. They must have their reasons, but it looks like they botched this.

Recently I took some trails through the mountains in Taipei and ended up at Shih Hsin University (Shìxīn Dàxué / 世新大學). Near the school are some interesting signs. Rather than giving individual posts for each of these, I’m keeping the signs together in this one, as this is better testimony to the increasing and often playful diversity of languages and scripts in Taiwan.

Cǎo Chuàn

Here’s a restaurant whose name is given in Pinyin with tone marks! That’s quite a rarity here, though I suspect we’ll be seeing more of this in the future. The name in Chinese characters (草串) can be found, much smaller, on a separate sign below.

二哥の牛肉麵

Right by Cao Chuan is Èrgē de Niúròumiàn (Second Brother’s Beef Noodle Soup). Note the use of the Japanese の rather than Mandarin’s 的; this is quite common in Taiwan.

芭樂ㄟ店

This store has an ㄟ, which serves as a marker of the Taiwanese language. Here, ㄟ is the equivalent of 的 — and of の.

A’Woo Tea Bar

I couldn’t find a name in Chinese characters for this place. The name is probably onomatopoeia, as in “Werewolves of London — awoo!”

Since I just posted about the new Hakka-based Chinese character input method I would be amiss not to note as well the release early this year of a different Chinese character input method based on Taiwanese romanization.

Since I just posted about the new Hakka-based Chinese character input method I would be amiss not to note as well the release early this year of a different Chinese character input method based on Taiwanese romanization.

This one is available in Windows, Mac, and Linux flavors.

See the FAQ and documents below for more information (Mandarin only).

Táiwān Mǐnnányǔ Hànzì shūrùfǎ 2.0 bǎn xiàzài (臺灣閩南語漢字輸入法 2.0版下載) [Readers may wish to note the use of Minnan, which is generally preferred among unificationists and some advocates of Hakka and the languages of Taiwan’s tribes.]

source: Jiàoyùbù Táiwān Mǐnnányǔ Hànzì shūrùfǎ (教育部臺灣閩南語漢字輸入法); Ministry of Education, Taiwan; June 16, 2010(?) / February 14, 2011(?) [Perhaps the Windows and Linux versions came first, with the Mac version following in 2011.]