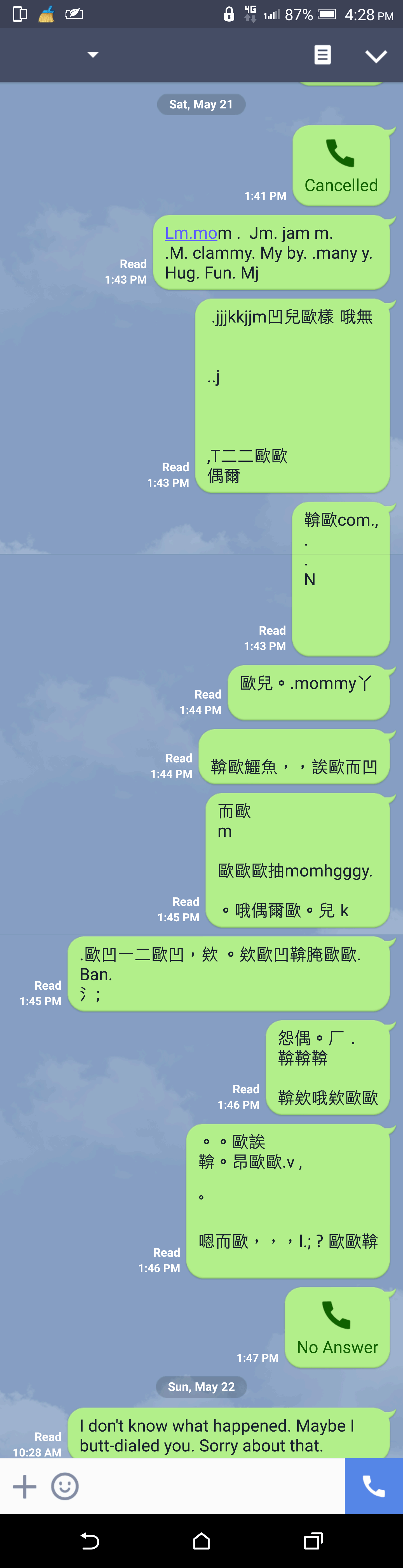

Commonwealth Magazine (Tiānxià zázhì) recently interviewed me for a Mandarin-language piece related to the signage on Taipei’s MRT system.

As anyone who has looked at Pinyin News more than a couple of times over the years should be able to guess, I had a lot to say about that — most of which understandably didn’t make it into the article. For example, I recall making liberal use of the word “bèn” (“stupid”) to describe the situation and the city’s approach. But the reporter — Yen Pei-hua (Yán Pèihuá / 嚴珮華), who is perhaps Taiwan’s top business journalist — diplomatically omitted that.

Since the article discusses the nicknumbering system Taipei is determined to implement “for the foreigners,” even though most foreigners are at best indifferent to this, but doesn’t include my remarks on it, I’ll refer you to my post on this from last year: Taipei MRT moves to adopt nicknumbering system. Back then, though, I didn’t know the staggering amount of money the city is going to spend on screwing up the MRT system’s signs: NT$300 million (about US$10 million)! The main reason given for this is the sports event Taipei will host next summer. That’s supposed to last for about ten days, which would put the cost for the signs alone at about US$1 million per day.

On the other hand, the city does not plan to fix the real problems with the Taipei MRT’s station names, specifically the lack of apostrophes in what should be written Qili’an (not Qilian), Da’an (not Daan) (twice!), Jing’an (not Jingan), and Yong’an (not Yongan) — in Chinese characters: 唭哩岸, 大安, 景安, and 永安, respectively. And then there’s the problem of wordy English names.

Well, take a look and comment — here, or better still, on the Facebook page. (Links below.) I’m grateful to Ms. Yen and Commonwealth for discussing the issue.

References:

- Wèishénme 3000 wàn zuò biānmǎ — wàiguórén háishi zhǎobudào Táiběi jiéyùn zhàn? (為什麼3000萬做編碼 外國人還是找不到台北捷運站?), Commonwealth Magazine (Tiānxià zázhì / 天下雜誌), October 26, 2016

- Facebook page for the Commonwealth article