The Shanghai Daily has a profile of Lu Gusun (Lù Gǔsūn, 陆谷孙, 陸谷孫), editor-in-chief of the plainly titled English-Chinese Dictionary (Yīng-Hàn dà cídiǎn, 《英漢大詞典》). The second edition of this dictionary, which was released earlier this month, contains more than 20,000 new entries, an increase of some 10 percent.

Lu has spent most of his academic life at Fudan University, at which in 1965 he earned a master’s in foreign languages and literature. He stayed on as a teacher specializing in Shakespeare. But then came the Cultural Revolution. “Those were the days when the world could not tolerate a peaceful desk for study,” Lu said simply.

Criticized as bourgeois, he had to recite the poems of Alexander Pushkin after a day’s hard labor.

I wonder if the reporting here is accurate, as being forced to recite Pushkin would have been a very strange punishment from a number of standpoints — even in those very strange times.

Lu was forced out of teaching and assigned to compile dictionaries.

In 1970, Lu participated in compiling the New English-Chinese Dictionary, which is still available and has sold more than 10 million copies over the years.

One of the reasons for its vitality was the fact that Lu “smuggled” in many up-to-date words and expressions. Otherwise it would have been staid and quickly dated….

In 1975, Lu and a team of scholars started work on the English-Chinese Dictionary and he was appointed editor-in-chief in 1986.

It took them 16 years to finish the award-winning dictionary, and the team of compilers shrank to 17 people from 108 at the peak.

“To compile a dictionary, you have to bear the loneliness and resist various temptations,” says Lu. “Many partners gave it up for more lucrative posts, some went abroad, some started their own businesses and some died out of devotion to the creation of the dictionary.” A compiler in his 40s passed away just three months before the dictionary was published.

As for Lu, he used coffee, cigarettes, mustard and even alcohol to sustain his fighting spirit. He promised not to go abroad, publish books or take any part-time teaching jobs until the dictionary was complete….

“It is a solemn battle,” says Lu. “Only those who have experienced this can understand the solemnity…. The process of dictionary compilation is always plagued by the four Ds — namely, delays, deficits, delinquencies and deficiencies. But there is spiritual ecstasy that you can hardly experience elsewhere.”

Although Lu has formally retired from Fudan University, he continues to deliver popular lectures in English twice a week to freshmen, and he advises graduate students.

“I hope colleges can be a wonderland, not a wasteland for young people. They should have their minds sharpened and their lives enriched here,” he says.

“Some colleges now make training leaders their main target. But this goal can deprive students of many pure pleasures and undermine their enthusiasm for academic achievements,” the professor adds.

source: Prof inspires ‘spiritual ecstasy’, Shanghai Daily, May 15, 2007

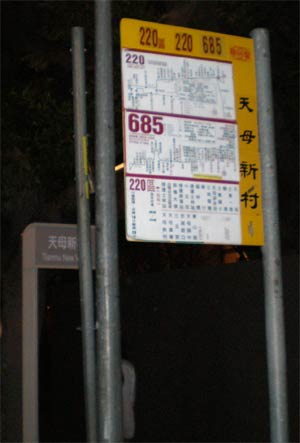

The Taipei City Government has begun to replace busstop signs throughout the city.

The Taipei City Government has begun to replace busstop signs throughout the city.