I’ve already written some about campaign banners and literacy. But it’s campaign season again in Taiwan, with elections for neighborhood chiefs to be held this Saturday, and Taffy of Taiwanease.com and Tailingua has sent me a photo of a campaign banner that features zhuyin fuhao (also known as bopo mofo) alongside the characters for the candidate’s given name. That’s the sort of thing I can’t resist.

I’ve already written some about campaign banners and literacy. But it’s campaign season again in Taiwan, with elections for neighborhood chiefs to be held this Saturday, and Taffy of Taiwanease.com and Tailingua has sent me a photo of a campaign banner that features zhuyin fuhao (also known as bopo mofo) alongside the characters for the candidate’s given name. That’s the sort of thing I can’t resist.

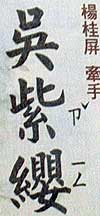

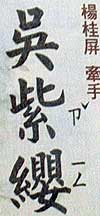

The banner is interesting not only in that it gives zhuyin but also that it gives zhuyin for just some of the characters. For the name Wú Zǐ-yīng (吳紫纓) we are given:

吳

紫 ㄗˇ

纓 ㄧㄥ

(See detail at top right.)

That zhuyin is not used for all of the characters in the name indicates that those who created the banner regarded the zhuyin as advisable for two of the characters. Yet the only character here that is particularly uncommon is the last one: 纓. It is used for yīngzi (纓子), a word for “tassel.”

吳, used for the family name Wu, is a fairly common character and is not displayed with zhuyin.

On the other hand, 紫, which is used for zǐsè (紫色/purple), is roughly the 1,700th most common character. Thus, people of voting age in Taiwan should know this character; yet evidently that cannot be taken for granted. This rank would also mean that people living in China’s countryside, though not in the cities, could be declared “literate” even without being able to read or write this character. (This helps illustrate how standards in China are too low. And, even so, literacy figures there are greatly exaggerated.)

Please permit me to stress the obvious: There is nothing in the least bit obscure in Taiwan or China about the Mandarin word for “purple.” Zǐsè is a word that essentially all native speakers of Mandarin would know, regardless of education, just as essentially all native speakers of English would know the word “purple.” But because the powers that be continue to emphasize the exclusive use of Chinese characters, a sizable number of people are incapable of reading (much less writing) the word for “purple.” This extends even to thousands of other words within people’s vocabularies, a situation that would not exist if romanization were permitted as an orthography.

(I’m still wondering why no bloggers who focus more on Taiwan politics have picked up on what I wrote about before: Ballots in Taiwan do not identify a candidate’s political party in any way (not even a logo), except for presidential elections, which are the one election in which everyone already knows for sure the party affiliation of the major candidates. Am I the only person who thinks this is significant? But it’s off-topic for this site, so I’ll not pursue this further here.)

Oh, if anyone’s curious, the title of the Alice Walker book The Color Purple is translated in Taiwan as Zǐsè zǐ-mèihuā (紫色姊妹花).

I’ve already written some about

I’ve already written some about