Last week, on the same day President Ma Ying-jeou accepted the resignation of a minister who made some drunken lewd remarks at a wěiyá (year-end office party), Ma was joking to the media about blow jobs.

Classy.

But it was all for a good cause, of course. You see, the Mandarin expression chuī lǎba, when not referring to the literal playing of a trumpet, is usually taken in Taiwan to refer to a blow job. But in China, Ma explained, chuī lǎba means the same thing as the idiom pāi mǎpì (pat/kiss the horse’s ass — i.e., flatter). And now that we have the handy-dandy Zhōnghuá Yǔwén Zhīshikù (Chinese Language Database), which Ma was announcing, we can look up how Mandarin differs in Taiwan and China, and thus not get tripped up by such misunderstandings. Or at least that’s supposed to be the idea.

The database, which is the result of cross-strait cooperation, can be accessed via two sites: one in Taiwan, the other in China.

It’s clear that a lot of money has been spent on this. For example, many entries are accompanied by well-documented, precise explanations by distinguished lexicographers. Ha! Just kidding! Many entries are really accompanied by videos — some two hundred of them — of cutesy puppets gabbing about cross-strait differences in Mandarin expressions. But if there’s a video in there of the panda in the skirt explaining to the sheep in the vest that a useful skill for getting ahead in Chinese society is chuī lǎba, I haven’t found it yet. Will NMA will take up the challenge?

Much of the site emphasizes not so much language as Chinese characters. For example, another expensively produced video feeds the ideographic myth by showing off obscure Hanzi, such as the one for chěng.

WARNING: The screenshot below links to a video that contains scenes with intense wawa-ing and thus may not be suitable for anyone who thinks it’s not really cute for grown women to try to sound like they’re only thwee-and-a-half years old.

In a welcome bit of synchronicity, Victor Mair posted on Language Log earlier the same week on the unpredictability of Chinese character formation and pronunciation, briefly discussing just such patterns of duplication, triplication, etc.

Mair notes:

Most of these characters are of relatively low frequency and, except for a few of them, neither their meanings nor their pronunciations are known by persons of average literacy.

Many more such characters consisting or two, three, or four repetitions of the same character exist, and their sounds and meanings are in most cases equally or more opaque.

The Hanzi for chěng (which looks like 馬馬馬 run together as one character) in the video above is sufficiently obscure that it likely won’t be shown correctly in many browsers on most systems when written in real text: 𩧢. But never fear: It’s already in Unicode and so should be appearing one of these years in a massively bloated system font.

Further reinforcing the impression that the focus is on Chinese characters, Liú Zhàoxuán, who is the head of the association in charge of the project on the Taiwan side, equated traditional Chinese characters with Chinese culture itself and declared that getting the masses in China to recognize them is an important mission. (Liu really needs to read Lü Shuxiang’s “Comparing Chinese Characters and a Chinese Spelling Script — an evening conversation on the reform of Chinese characters.”)

Then he went on about how Chinese characters are a great system because, supposedly, they have a one-to-one correspondence with language that other scripts cannot match and people can know what they mean by looking at them (!) and that they therefore have a high degree of artistic quality (gāodù de yìshùxìng). Basically, the person in charge of this project seems to have a bad case of the Like Wow syndrome, which is not a reassuring trait for someone in charge of producing a dictionary.

The same cooperation that built the Web sites led to a new book, Liǎng’àn Měirì Yī Cí (《兩岸每日一詞》 / Roughly: Cross-Strait Term-a-Day Book), which was also touted at the press conference.

The book contains Hanyu Pinyin, as well as zhuyin fuhao. But, alas, the book makes the Pinyin look ugly and fails completely at the first rule of Pinyin: use word parsing. (In the online images from the book, such as the one below, all of the words are se pa ra ted in to syl la bles.)

The Web site also has ugly Pinyin, with the CSS file for the Taiwan site calling for Pinyin to be shown in SimSun, which is one of the fonts it’s better not to use for Pinyin. But the word parsing on the Web site is at least not always wrong. Here are a few examples.

- “跑神兒” is given as pǎoshénr (good).

- And apostrophes appear to be used correctly: e.g., fàn’ān (販安), chūn’ān (春安), and fēi’ān (飛安).

- But “第二春” is run together as “dìèrchūn” (no hyphen) rather than as shown correctly as dì-èr chūn.

- And “一個頭兩個大” is given as yíɡe tóu liǎnɡɡe dà (for Taiwan) and yīɡe tóu liǎnɡɡe dà (for China). But ge is supposed to be written separately. (The variation of tone for yi is in this case useful.)

Still, my general impression from this is that we should not expect the forthcoming cross-strait dictionary to be very good.

Further reading:

- Mǎ zǒngtǒng: fāzhǎn liǎng’àn tōngyòng wénzì (馬總統:發展兩岸通用文字), China Times, February 9, 2012

- Ma applauds cross-strait online Chinese dictionary, Taipei Times, February 9, 2012

- Online databases detail cross-strait languages, China Post, February 9, 2012

- Zǒngtǒng: Zhōngguó “chuī lǎba” děngyú Táiwān “pāi mǎpì” (總統:中國「吹喇叭」等於台灣「拍馬屁」), Yam News, February 8, 2012

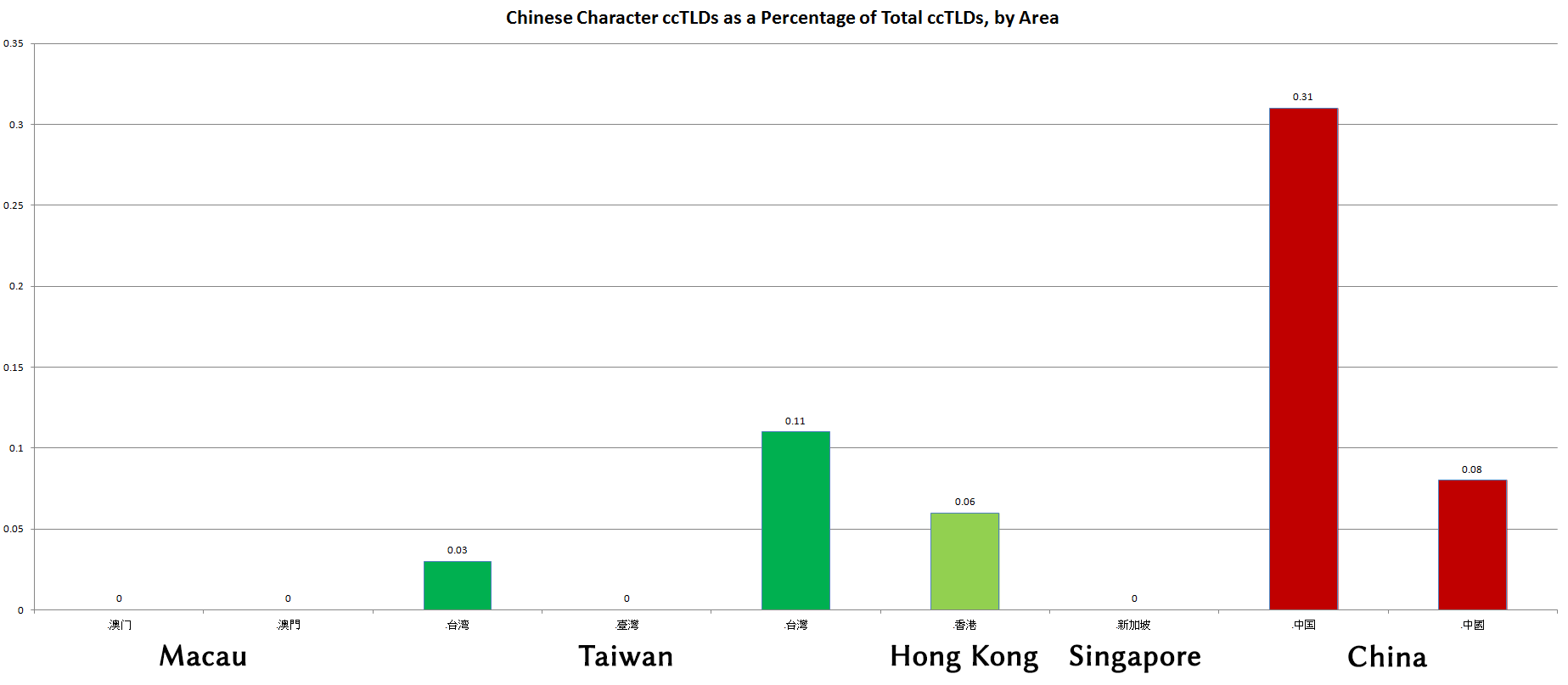

domains compare with the use of .tw domains?

domains compare with the use of .tw domains?  ), so it is omitted here.

), so it is omitted here. and

and  , so those figures are still at zero.

, so those figures are still at zero.  ccTLD, even though the Ma administration, which was in power when Taiwan’s ccTLDs went into effect, officially prefers the more complex form of

ccTLD, even though the Ma administration, which was in power when Taiwan’s ccTLDs went into effect, officially prefers the more complex form of  .

.