This season is the thirty-first anniversary of the reinstatement of China’s national college entrance examinations after the end of the disastrous Cultural Revolution. Here’s the story of something that happened the year of the reinstatement (1977), when Zhang Huiming, a professor in the Chinese department of Xianyang Normal College, grading exams from Xianyang, Shaanxi, and its surrounding areas.

That year, after the start of the third day of work grading the exams had begun, one of the teachers on the grading team suddenly shouted in amazement, “Come look at this exam!” There before all of us was a language exam that had been answered completely in Hanyu Pinyin. Facing this situation, everyone discussed it. Right away, some said, “This is simply horsing around, putting on a show. Give it a zero!” The head of the grading team was inclined toward this idea. But Zhang Huiming insisted on first putting the exam into Chinese characters. “Who wouldn’t allow such an exam? There’s no rule against it. And Chairman Mao long ago indicted, ‘Writing should follow the world’s common Pinyin trend [i.e., use an alphabet like everyone else].’”

Everyone fell silent. Zhang Huiming took about half an hour to annotate the Hanyu Pinyin with Chinese characters. It turned out that the exam was nearly without errors in spelling or tone marks. The score, to everyone’s surprise, was 88. The teachers who corrected the exams were all convinced by this examinee of the soundness of training in Hanyu Pinyin.

A nice story. But I can’t help but note sadly that a bunch of well-educated people didn’t simply read the essay as it was written. Such are the prejudices against it. What I’d really like is a story that doesn’t treat Pinyin as if it were merely a set of training wheels.

“Gāokǎo huīfù 30 nián” zhǔtí bàodào tuīchū hòu, hěn duō dúzhě fā lái diànzǐ yóujiàn, jiǎngshù dāngnián de gāokǎo gùshi. Xiányáng Shīfàn Xuéyuàn Zhōngwénxì jiàoshòu Zhāng Huìmín, shì 1977 nián Xiányáng dìqū yǔwén yuèjuàn lǎoshī zhīyī. Dāngnián, yī fèn wánquán yòng Hànyǔ Pīnyīn wánchéng de yǔwén dájuàn ràng tā zhìjīn nánwàng.

Dāngnián, yuèjuàn gōngzuò kāishǐ hòu de dì-sān tiān, yuèjuànzǔ yī lǎoshī tūrán jīngyà de shuō: “Kuài kàn, zhè fèn shìjuàn!” Yī piān wánquán yòng Hànyǔ Pīnyīn zuòdá de yǔwén shìjuàn chéngxiàn zài dàjiā miànqián. Suíhòu, zhè fèn tèshū de shìjuàn zài quántǐ lǎoshī zhōngjiān kāishǐ chuányuè. Miànduì zhè yī qíngkuàng, dàjiā yìlùnfēnfēn. Yǒurén dāngchǎng biǎoshì: “Jiǎnzhí jiùshì húnào, biāoxīnlìyì, gěi língfēn!” Yuèjuànzǔ zǔzhǎng yě qīngxiàng gāi yìjian. Dàn Zhāng Huìmín jiānchí yīng xiān jiāng kǎojuàn fānyì chéng Hànzì. “Shuí bù ràng tā zhèyàng dájuàn? Gāokǎo bìng méiyǒu bùyǔn xǔyòng Hànyǔ Pīnyīn zuò dá’àn de guīdìng, kuàngqiě Máo zhǔxí zǎojiù zhǐshì: ‘Wénzì yào zǒu shìjiè gòngtóng Pīnyīn de fāngxiàng.’”

Chénmò le yīhuìr zhīhòu, Zhāng Huìmín yòng jìn bàn ge xiǎoshí de shíjiān, gěi zhěng fèn dájuàn shàng de Hànyǔ Pīnyīn biāozhù le Hànzì. Ràng Zhāng Huìmín nányǐ wàngjì de shì, nà fèn kǎojuàn, yīnjié, shēngdiào jīhū méiyǒu cuòwù. Jiéguǒ, zhè fèn fèijìn zhōuzhé de yǔwén dájuàn jīng gě fùzé lǎoshī píngyuè hòu, zǒng fēn jìngrán shì 88 fēn. Quántǐ yuèjuàn lǎoshī dōu bèi zhè wèi kǎoshēng zhāshi de Hàn yǔyán gōngdǐ suǒ zhéfú.

source: Yī fèn yòng pīnyīn wánchéng de yǔwén shìjuàn (一份用拼音完成的语文试卷), Huash.com, March 27, 2007

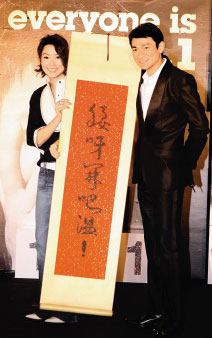

Joel of Danwei has posted about an interesting calligraphy scroll presented to Hong Kong superstar Andy Lau.

Joel of Danwei has posted about an interesting calligraphy scroll presented to Hong Kong superstar Andy Lau.