Some recent comments on the Hanzi domain name situation brought to mind a rant I was working on last month and then abandoned. But it seems worth finishing — relatively speaking, because this is a topic that touches upon so many areas that I could never get through it all — because the problem I discuss is a fairly common one. So today I’d like to address what I think of as the “like, wow” fetish of Chinese characters. In this, Chinese characters are regarded as if they bestowed a wonderful gift upon the reader that no other script could. But exactly how they do that and what exactly that gift is, though, generally doesn’t make too much sense.

This sort of thing is common, and not just among New Age nonsense. A good example of this approach is found in Search Engine of the Song Dynasty, an op-ed piece published in the New York Times in mid May. Basically, the author discusses how having URLs in Chinese characters is a good thing, but does so in a vague, flowery way that brings to mind a stoned grad student with a large vocabulary — which might not be so bad if the author had gotten the facts straight.

I had hoped for at least a little better, given that the author, Ruiyan Xu, has completed a novel, The Lost and Forgotten Languages of Shanghai, whose protagonist has bilingual aphasia. So one would expect Xu, who was born in Shanghai and moved to the United States at the age of 10, to have a better-than-basic understanding of linguistics. Alas, no — not if the article is anything to go by.

My annoyance here, though, isn’t specifically with Xu, who seems like a nice person and whose book has been getting some good advance reviews. It’s more with the “like, wow” phenomenon in general and the eagerness of the mainstream press to publish things about “Chinese” even though the substance of such articles falls apart if one devotes even just a little effort to examining it.

So let’s get into it.

Baidu.com, the popular search engine often called the Chinese Google, got its name from a poem written during the Song Dynasty (960-1279). The poem is about a man searching for a woman at a busy festival, about the search for clarity amid chaos. Together, the Chinese characters bi [sic] and dù mean “hundreds of ways,” and come out of the last lines of the poem: “Restlessly I searched for her thousands, hundreds of ways./ Suddenly I turned, and there she was in the receding light.”

For reference, I’ll provide the poem. I’ve put the Chinese characters used by Baidu.com in bold and red.

東風夜放花千樹。

更吹落、星如雨。

寶馬雕車香滿路。

鳳簫聲動,

玉壺光轉,

一夜魚龍舞。蛾兒雪柳黃金縷。

笑語盈盈暗香去。

眾裡尋他千百度。

驀然迴首,

那人卻在,

燈火闌珊處。

The author of the poem, Xin Qiji (Xīn Qìjī / 辛棄疾 / 辛弃疾), lived from 1140 to 1207 and was thus a contemporary of such Western poets as the troubadours Bertran de Born, Bernart de Ventadorn, and Giraut de Borneil — hardly poets whose work suffered for having been written with an alphabet.

Baidu, rendered in Chinese, is rich with linguistic, aesthetic and historical meaning. But written phonetically in Latin letters (as I must do here because of the constraints of the newspaper medium and so that more American readers can understand), it is barely anchored to the two original characters; along the way, it has lost its precision and its poetry.

Ugh. Where to start?

I’ll go ahead and skip “precision,” even though that’s perhaps not a word best applied to most poetry written in Literary Sinitic, and start with “rendered in Chinese.” However common the word might be, “Chinese” is a poor choice. In this case, the word seems to be intended to mean not any particular language but rather “Chinese characters,” which are not a language. Here, too, she appears to be blaming Pinyin for having lost something from Literary Sinitic, which is what the poem was written in. But Pinyin isn’t for Literary Sinitic; it’s for modern standard Mandarin. Also, whatever language Xin Qiji spoke could have been written with an alphabet with no loss of meaning, just like all other natural languages.

As Web addresses increasingly transition to non-Latin characters as a result of the changing rules for domain names, that series of Latin letters Chinese people usually see at the top of the screen when they search for something on Baidu may finally turn into intelligible words: “a hundred ways.”

Baidu vs. 百度 on the Baidu.com home page:

Can you feel the difference in precision and poetry? No?

Also, it’s not clear just how much of a “transition to non-Latin characters” there’s going to be, especially where Chinese characters are concerned, especially in places like Singapore.

Of course, this expansion of languages for domain names could lead to confusion: users seeking to visit Web sites with names in a script they don’t read could have difficulty putting in the addresses, and Web browsers may need to be reconfigured to support non-Latin characters. The previous system, with domain names composed of numbers, punctuation marks and Latin letters without accents, promoted standardization, wrangling into consistency and simplicity one small part of the Internet.

For “could have difficulty putting in the addresses” read “could find it next to impossible to enter the correct address.” And by “one small part of the Internet,” she appears to mean the name of every single domain on the entire Internet.

But something else, something important, has been lost.

Part of the beauty of the Chinese language comes from a kind of divisibility not possible in a Latin-based language. Chinese is composed of approximately 20,000 single-syllable characters, 10,000 of which are in common use.

No, no, and no.

- By “Latin-based language” the author seems to be referring not to a Romance language but to a language that uses the Latin alphabet for its standard script.

- What exactly is this divisibility? Mandarin words can be divided into morphemes. The words of English, French, etc. work the same way.

- No language is composed of Chinese characters.

- There are a hell of a lot more than 20,000 Chinese characters.

- “Common use” is difficult to pin down. But most authorities would give a lower number.

These characters each mean something on their own; they are also combined with other characters to form hundreds of thousands of multisyllabic words.

No, that’s wrong. Again: words — whether they be multisyllabic or monosyllabic — are not made of Chinese characters. Instead, Chinese characters are the script most seen for written Mandarin.

Níhăo, for example, Chinese for “Hello,” is composed of ní — “you,” and hăo — “good.” Isn’t “You good” — both as a statement and a question — a marvelous and strangely precise breakdown of what we’re really saying when we greet someone?

Again, this is assigning meaning to characters, when the meaning is of course in the word itself.

Note, too, that “níhăo” is incorrect in several ways.

- One of the basic rules of Hanyu Pinyin is that tone sandhi is not indicated. So even though — because in Mandarin if something has two third tones in a row, the first shifts to second tone — the greeting is pronounced níhǎo, the diacritical mark over the i should indicate third tone (ǐ) rather than second (í).

- The diacritic over the a is wrong. It should be ǎ (Unicode ̌), not ă (Unicode ă) — sharp vs. rounded. (You may need to enlarge the fonts on the screen to see this.)

- Most careful authorities write this with a space rather than as solid: nǐ hǎo rather than nǐhǎo. This, though, is something I don’t much care about. Popular usage of Pinyin as a real script will eventually work this out one or the other. Also, if someone is going to err in word parsing, I’d much rather they do it by making words solid rather than by breaking up the syllables.

The Romanization of Chinese into a phonetic system called Pinyin, using the Latin alphabet and diacritics (to indicate the four distinguishing tones in Mandarin), was developed by the Chinese government in the 1950s.

I’m a bit surprised the copy editors at the New York Times let that muddled sentence though. But I’ll pass over it without further observation.

Pinyin makes the language easier to learn and pronounce, and it has the added benefit of making Chinese characters easy to input into a computer. Yet Pinyin, invented for ease and standards, only represents sound.

In other words, Pinyin represents language — that being what writing systems are designed to do. And, yes, it’s easy to learn and use, which happens to be a good thing, not a bad one.

In Chinese, there are multiple characters with the exact same sound. The sound “băi,” for example, means 100, but it can also mean cypress, or arrange. And “Baidu,” without diacritics, can mean “a failed attempt to poison” or “making a religion of gambling.”

My dictionary gives some different phrases. But whatever. Then there’s also the simple point: If there’s a problem with writing Pinyin without diacritics, then don’t write Pinyin without diacritics, write it with diacritics. But I have a hard time imagining how anyone would get such things confused in context.

Q: “Honey, could you check Baidu for information on when that new movie is coming out?”

A: “Baidu? Sorry, could you write that in Chinese characters for me. I can’t tell if you mean “a failed attempt to poison,” “making a religion of gambling,” or the search engine.”

Behind this is just the usual homonym canard. In English, as in other languages, there are many morphemes with the exact same pronunciation (sound). If we look at the closest English has to the Mandarin sounds bai and du, we can get by, buy, bye, bi-, and dew, do, due, etc. — all of which have various meanings. Take a look.

Those who don’t need to be hit over the head again and again to understand the simple point that English has plenty of homonyms but does just fine with an alphabet — as would every other natural language, including of course Mandarin and the other Sinitic languages– may wish to just skim the following blockquote.

bi, bi-, buy, by, bye

buy (transitive verb)

- : to acquire possession, ownership, or rights to the

use or services of by payment especially of money :

purchase

- : to obtain in exchange for something often at

a sacrifice <they bought peace with their

freedom>- : redeem

- : bribe, hire

- : to be the purchasing equivalent of <the dollar

buys less today than it used to>- : accept, believe <I don’t buy that hooey> -often

used with intobuy (intransitive verb)

- : to make a purchase

buy (noun)

- : something of value at a favorable price; especially :

bargain <it’s a real buy at that price>- : an act of buying : purchase

bi (noun or adjective)

- : bisexual

bi- (prefix)

- : two <bilateral>

- : coming or occurring every two

<bicentennial>- : into two parts <bisect>

- : twice : doubly : on both sides

<biconvex>- : coming or occurring two times

<biannual> – compare semi-- : between, involving, or affecting two (specified)

symmetrical parts <bilabial>

- : containing one (specified) constituent in

double the proportion of the other constituent or

in double the ordinary proportion

<bicarbonate>- : di- 2 <biphenyl>

bi- (Variant(s): or bio-) (combining form)

- : life : living organisms or tissue

<bioluminescence> <biosphere>- : biographical <biopic>

bye (noun)

- : the position of a participant in a tournament who

advances to the next round without playingby (preposition)

- : in proximity to : near <standing by the

window>

- : through or through the medium of : via

<enter by the door>- : in the direction of : toward <north by

east>- : into the vicinity of and beyond : past

<went right by him>

- : during the course of <studied by

night>- : not later than <by 2 p.m.>

- : through the agency or instrumentality of

<by force>- : born or begot of

- : sired or borne by

- : with the witness or sanction of <swear by all that

is holy>

- : in conformity with <acted by the

rules>- : according to <called her by name>

- : on behalf of <did right by his

children>- : with respect to <a lawyer by

profession>

- : in or to the amount or extent of <win by a

nose>- b chiefly Scottish : in comparison with :

beside- -used as a function word to indicate successive units or increments <little by little> <walk two by two>

- -used as a function word in multiplication, in division, and in measurements <divide a by b>

<multiply 10 by 4> <a room 15 feet by 20 feet>- : in the opinion of : from the point of view of

<okay by me>by (adjective)

- : being off the main route : side

- : incidental

by (noun)

- : something of secondary importance : a side issue

by/bye (interjection)

- : short for goodbye

dew, do, due

dew (noun)

- : moisture condensed upon the surfaces of cool bodies especially at night

- : something resembling dew in purity, freshness, or power to refresh

- : moisture especially when appearing in minute droplets: as

- : tears

- : sweat

- : droplets of water produced by a plant in transpiration

due (adjective)

- : owed or owing as a debt

- : owed or owing as a natural or moral right

<everyone’s right to dissent is due the full protection of the Constitution – Nat Hentoff>- : according to accepted notions or procedures : appropriate <with all due respect>

- : satisfying or capable of satisfying a need, obligation, or duty : adequate <giving the matter due attention>

- : regular, lawful <due proof of loss>

- : capable of being attributed : ascribable -used with to <this advance is partly due to a few men of genius –

A. N. Whitehead>- : having reached the date at which payment is required

: payable <the rent is due>- : required or expected in the prescribed, normal, or logical course of events : scheduled <the train is due at noon>; also : expected to give birth

due (noun)

- : something due or owed: as

- : something that rightfully belongs to one

<give him his due>- : a payment or obligation required by law or custom : debt

- plural : fees, charges <membership dues>

due (adverb)

- : directly, exactly <due north>

- <obsolete> : duly

do (transitive verb)

- : to bring to pass : carry out <do another’s wishes>

- : put -used chiefly in do to death

- : perform, execute

- <do some work> <did his duty>

- : commit <crimes done deliberately>

- : bring about, effect <trying to do good>

<do violence>- : to give freely : pay <do honor to her memory>

- : to bring to an end : finish -used in the past participle <the job is finally done>

- : to put forth : exert <did her best to win the race>

- : to wear out especially by physical exertion : exhaust

<at the end of the race they were pretty well done> b

: to attack physically : beat; also : kill- : to bring into existence : produce <do a biography on the general>

- -used as a substitute verb especially to avoid

repetition <if you must make such a racket, do it

somewhere else>- : to play the role or character of b : mimic; also : to behave like <do a Houdini and disappear> c : to perform in or serve as producer of <do a play>

- : to treat unfairly; especially : cheat <did him out of his inheritance>

- : to treat or deal with in any way typically with the sense of preparation or with that of care or attention:

- : to put in order : clean <was doing the kitchen>

- : wash <did the dishes after supper>

- : to prepare for use or consumption; especially : cook <like my steak done rare>

- : set, arrange <had her hair done>

- : to apply cosmetics to <wanted to do her face before the party>

- : decorate, furnish <did the living room in Early American> <do over the kitchen>

- : to be engaged in the study or practice of <do science>; especially : to work at as a vocation lt;what to do after college>

- : to pass over (as distance) : traverse <did 20 miles yesterday>

- : to travel at a speed of <doing 55 on the turnpike>

- : tour <doing 12 countries in 30 days>

- : to spend (time) in prison <has been doing time in a federal penitentiary>

- : to serve out (a period of imprisonment)

<did ten years for armed robbery>- : to serve the needs of : suit, suffice <worms will do us for bait>

- : to approve especially by custom, opinion, or propriety <you oughtn’t to say a thing like that — it’s not done – Dorothy Sayers>

- : to treat with respect to physical comforts <did themselves well>

- : use 3 <doesn’t do drugs>

- : to have sexual intercourse with

- : to partake of <let’s do lunch>

do (intransitive verb)

- : act, behave <do as I say>

- : get along, fare <do well in school>

- : to carry on business or affairs : manage

<we can do without your help>- : to take place : happen <what’s doing across the street>

- : to come to or make an end : finish -used in the past participle

- : to be active or busy <let us then be up and doing

– H. W. Longfellow>- : to be adequate or sufficient : serve <half of that will do>

- : to be fitting : conform to custom or propriety

<won’t do to be late>- -used as a substitute verb to avoid repetition

<wanted to run and play as children do> ; used especially in British English following a modal auxiliary or perfective have <a great many people had died, or would do – Bruce Chatwin>- -used in the imperative after an imperative to add emphasis <be quiet do>

do (verbal auxiliary)

- -used with the infinitive without to to form present and past tenses in legal and parliamentary language <do hereby bequeath> and in poetry <give what she did crave – Shakespeare>

- -used with the infinitive without to to form present and past tenses in declarative sentences with inverted word order <fervently do we pray –

Abraham Lincoln>, in interrogative sentences

<did you hear that?>, and in negative sentences <we don’t know> <don’t go>- -used with the infinitive without to to form present and past tenses expressing emphasis <i do say> <do be careful>

do (noun)

- chiefly dialect : fuss, ado

- archaic : deed, duty

- : a festive get-together : affair, party

- chiefly British : battle

- : a command or entreaty to do something <a list of dos and don’ts>

- British : cheat, swindle

- : hairdo

All that’s without me bothering to get out a big dictionary.

Alas, poor English! How confused we must be to be using a mere alphabet. Oh, if only we could achieve linguistic, aesthetic, and historical meaning!

In the case of Baidu.com, the word, in Latin letters, has slipped away from its original context and meaning, and been turned into a brand.

Baidu is a brand, and as is generally thought of as such regardless of what script it is written in. Furthermore, it’s understood as a “word” only as that search engine. In the poem the characters “百度” are used to write not one word but two — and even written in Hanzi this is not something more than a relative handful of people in China or Taiwan would recognize as having come from that poem unless someone told them about it first.

Language is such a basic part of our lives, it seems ordinary and transparent. But language is strange and magical, too: it dredges up history and memory; it simultaneously bestows and destabilizes meaning. Each of the thousands of languages spoken around the world has its own system and rules, its own subversions, its own quixotic beauty. Whenever you try to standardize those languages, whether on the Internet, in schools or in literature, you lose something. What we gain in consistency costs us in precision and beauty.

When Chinese speakers Baidu (like Google, it too is a verb), we look for information on the Internet using a branded search engine. But when we see the characters for băi dù, we might, for one moment, engage with the poetry of our language, remember that what we are really trying to do is find what we were seeking in the receding light. Those sets of meanings, layered like a palimpsest, might appear suddenly, where we least expect them, in the address bar at the top of our browsers. And in some small way, those words, in our own languages, might help us see with clarity, and help us to make sense of the world.

Clarity? Clarity?!

I understand that the author, as a novelist rather than a linguist, might be preoccupied with the whole Ezra Pound “make it new” and “give people new eyes” thing. If so, good for her. But, still, one should not not confuse flights of fancy, no matter how cool they might sound, with facts and should at least attempt not to be completely wrong about almost everything, especially when publishing in the New York Times.

If the argument for Chinese characters is supposed to be that their continued, indeed expanded, use is necessary so people can quote poems in Literary Sinitic out of context so that what would be at best a low-single-digit percentage of native speakers of Mandarin or another modern Sinitic language might recognize the allusion despite a lack of context and might get a Hanzi-licious frisson out of the experience … that would have to be one of the most ridiculous things I’ve ever read.

Kicking the irony meter way up on all this is that the author of those remarks on the really cool feelings one can get from reading Chinese characters cannot herself read texts written in them, though she neglected to mention that little bit of information in her New York Times piece.

And for irony on top of irony, as someone who left China at the age of 10, she likely still knows her native Sinitic language, so texts written in romanization could give her the literacy in that language that she lacks in Chinese characters. Romanization could provide meaning; but instead she harps upon the virtues of Chinese characters.

Oh, and for a final bit of irony, here’s something else the author apparently didn’t bother to check: 百度.com already exists. And is anyone surprised to hear that the site at that address is not a search engine of the Song dynasty? Here’s what it looks like.

That’s right: 百度.com is just a linkspam site. But apparently because, unlike baidu.com, it has Chinese characters in the URL it’s linkspam with its own quixotic beauty; it’s linkspam with its own sets of meanings, layered like a palimpsest; and it’s linkspam that is rich with linguistic, aesthetic and historical meaning.

C’mon, people! Feel the poetry of it! The precision!

Like, wow.

The magnificent Grand dictionnaire Ricci de la langue chinoise, better known as

The magnificent Grand dictionnaire Ricci de la langue chinoise, better known as

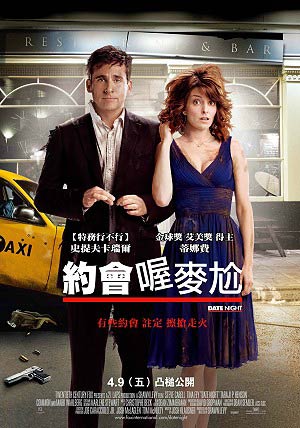

In Taiwan, the new movie Date Night has been given the Mandarin title

In Taiwan, the new movie Date Night has been given the Mandarin title

A review in a

A review in a