A common claim about Chinese characters (Hanzi) is that they take less space than alphabetic systems and so using them “saves paper.” After all, there aren’t spaces between words when writing in Chinese characters, and Chinese characters handle entire syllables rather than having to spell them out letter by letter. So this claim would seem to be self-evident. But things don’t always work out as expected.

A few weeks ago I was browsing the shelves of the enormous, wonderful Eslite bookstore near Taipei City Hall. (Nobody seems quite sure how the so-called English name of this chain is supposed to be pronounced, so many foreigners here prefer the Mandarin name: Chéngpǐn (誠品).) In many of the store’s sections, English-language originals and their translations into Mandarin are shelved right next to each other. So, after looking at a science book in English I pulled out the Mandarin Chinese translation of the same work and browsed through it. While I was doing so, I noticed something unexpected: the Mandarin version was longer than the English-language original.

This sparked my interest, so I pulled out some more paired titles, more or less at random, off the shelves for the purpose of comparison.

I did my best to keep the comparisons fair. In almost all of the cases I compared pairs of trade paperbacks: standard trade paperbacks in English with standard trade paperbacks in Mandarin.

Also, I didn’t count the pages taken up by indexes, since none of the translations into Mandarin had indexes. (Alphabets win hands down over Chinese characters when it comes to creating and using indexes, and I saw no reason to penalize the English books for this by counting pages that the ones in Chinese characters didn’t have the equivalent of.)

In addition, I avoided old books, since I wanted to be fairly sure the Mandarin Chinese translations were from the same English text as I was looking at. (I do, however, have one book written in German and translated into English. I didn’t check to see if the Mandarin version was done from the German original or the English translation.)

Of course, comparing across scripts and languages is certainly not the same as comparing simply across scripts (Hanzi vs. Hanyu Pinyin); but one does what one can.

Later, when I was supplementing my survey at the Eslite bookstore on Dunhua South Road when I noticed an error in my original method: I had forgotten to check where in the book page 1 fell. Many (but not all) English-language books mark the first page of the first chapter as page 1; many (but not all) books printed in Taiwan, however, include the front matter in their pagination, which leads to the first page of the first chapter being page 10 or so. So to help compensate for my oversight, it might be fair to subtract 10 pages from the Mandarin versions of those titles below followed by an asterisk. (The ones without an asterisk are those I examined most recently — and more carefully.)

Here are the results of my admittedly brief and unscientific survey:

Chronicles, Vol. 1, by Bob Dylan

English: 291 pp.

Mandarin in Hanzi: 295 pp.

Collapse, by Jared Diamond

English: 560 pp.

Mandarin in Hanzi: 609 pp.

The Death of Vishnu, by Manil Suri

English: 283 pp.

Mandarin in Hanzi: 287 pp.

Deep Simplicity: Bringing Order to Chaos and Complexity*, by John Gribbin

English: 235 pp.

Mandarin in Hanzi: 255 pp.

Did Adam and Eve Have Navels?: Debunking Pseudoscience*, by Martin Gardner

English: 310 pp.

Mandarin in Hanzi: 367 pp.

The Elegant Universe*, by Brian Greene

English: 428 pp.

Mandarin in Hanzi: 463 pp.

The Enigma of Arrival, by V.S. Naipaul

English: 350 pp.

Mandarin in Hanzi: 422 pp.

Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince, by J.K. Rowling

English: 607 pp. (hardback)

Mandarin in Hanzi: 716 pp.

Laboratory Earth*, by Stephen H. Schneider

English: 169 pp.

Mandarin in Hanzi: 227 pp.

The Long Tail, by Chris Anderson

English: 226 pp. (hardback, slightly larger than the Mandarin trade paperback)

Mandarin in Hanzi: 313 pp. (written left to right)

Perfume*, by Patrick Su?skind

English: 255 pp. (translation from German)

Mandarin in Hanzi: 278 pp.

Tough Choices, by Carly Fiorina

English: 309 pp.

Mandarin in Hanzi: 341 pp.

Vernon God Little, by D.B.C. Pierre

English: 275 pp. (mass market paperback)

Mandarin in Hanzi: 325 pp.

In every instance, the books in Chinese characters are longer than those in English. Moreover, the pages in the Mandarin-language trade paperbacks are somewhat larger than those in the English-language trade paperbacks. So that’s even more paper consumed by the books written in Chinese characters.

Although I certainly do not believe that all pairs of books in English and Mandarin translation follow this pattern, a pattern this very much appears to be.

My guess would be that books printed in China would have fewer pages than those printed in Taiwan. (Anyone want to check some of the above titles? Or does anyone have pairs of other titles in unexpurgated editions?) In general, books in China simply aren’t designed and printed with the same degrees of competency, attention, and concern for the reader as books in Taiwan — not to mention books in the United States and Britain. (Or have things changed very much in this regard since I lived in China?) So, among other factors, the characters tend to be smaller, along with the leading and the margins.

And then there’s the fact that translations in China sometimes omit sentences or entire sections, especially if they are deemed “sensitive.” (I doubt, however, that the books I examined suffered from Beijing’s censors.)

Also, China’s left-to-right format might have an advantage over Taiwan’s predominant top-to-bottom style in terms of space.

Something written with three different scripts (Chinese characters, zhuyin, and the roman alphabet) is very much the sort of thing that attracts my attention, as is a product that mixes scripts in its name. So this ad for a new product from Taiwan’s Pizza Hut definitely caught my eye, though it did not inspire me to actually taste the item being touted, which is a rice pizza. (Generally, I do not care for pizzas with Taiwanese characteristics, such as those with peas, corn, or squid. For that matter, I don’t even like pineapple on pizza.)

Something written with three different scripts (Chinese characters, zhuyin, and the roman alphabet) is very much the sort of thing that attracts my attention, as is a product that mixes scripts in its name. So this ad for a new product from Taiwan’s Pizza Hut definitely caught my eye, though it did not inspire me to actually taste the item being touted, which is a rice pizza. (Generally, I do not care for pizzas with Taiwanese characteristics, such as those with peas, corn, or squid. For that matter, I don’t even like pineapple on pizza.)

The

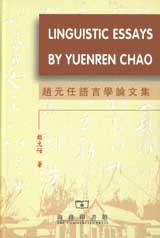

The  Note how the cover of Linguistic Essays, a book printed just last year in China, uses “Yuenren Chao,” the traditional spelling and Western order of his name, rather than “Zhao Yuanren,” the spelling used in Hanyu Pinyin. Also note how the Mandarin title is given in traditional, not simplified, characters: 趙元任語言學論文集, not 赵元任语言学论文集. A nice surprise, on both counts. On the other hand, the botched romanization on the cover of the Mandarin-language collection, which gives “ZHAOYUANREN YUYANXUELUNWENJI” instead of “

Note how the cover of Linguistic Essays, a book printed just last year in China, uses “Yuenren Chao,” the traditional spelling and Western order of his name, rather than “Zhao Yuanren,” the spelling used in Hanyu Pinyin. Also note how the Mandarin title is given in traditional, not simplified, characters: 趙元任語言學論文集, not 赵元任语言学论文集. A nice surprise, on both counts. On the other hand, the botched romanization on the cover of the Mandarin-language collection, which gives “ZHAOYUANREN YUYANXUELUNWENJI” instead of “