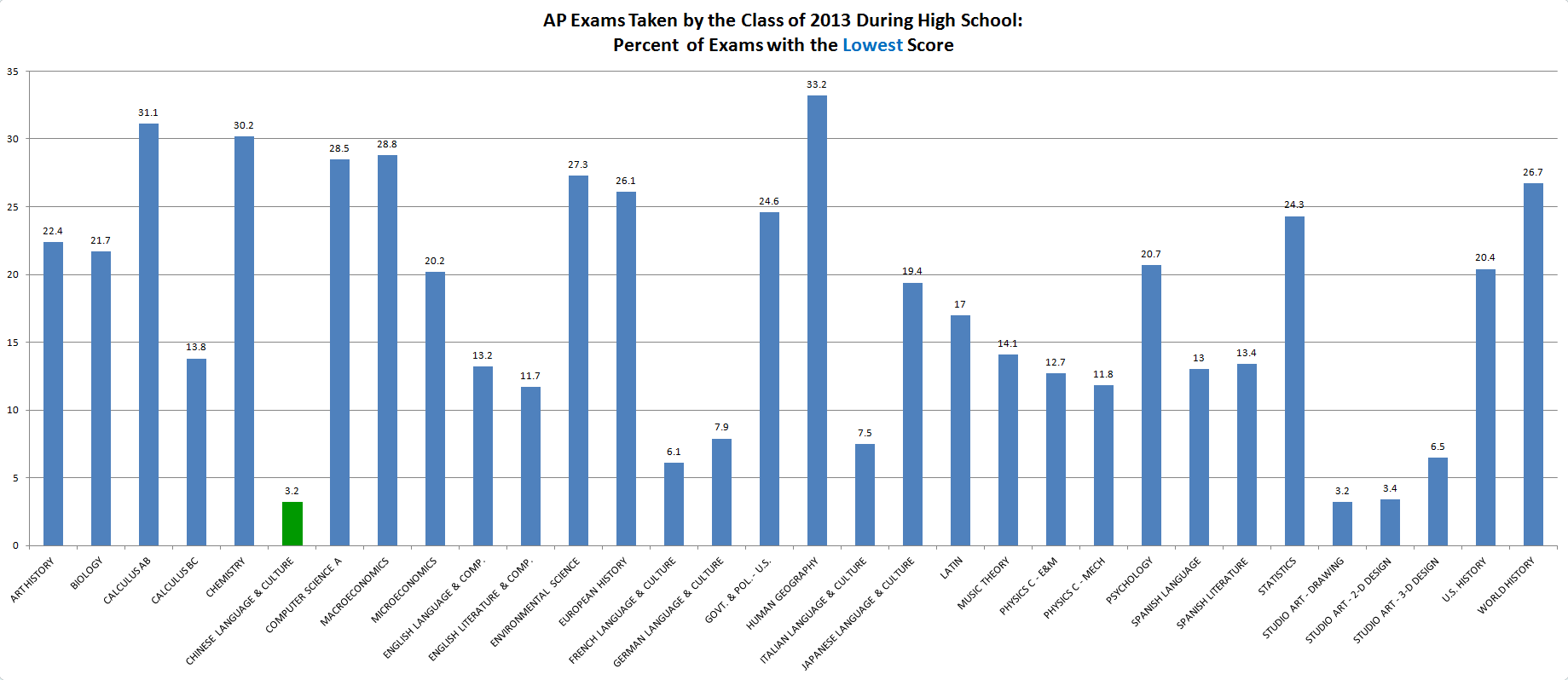

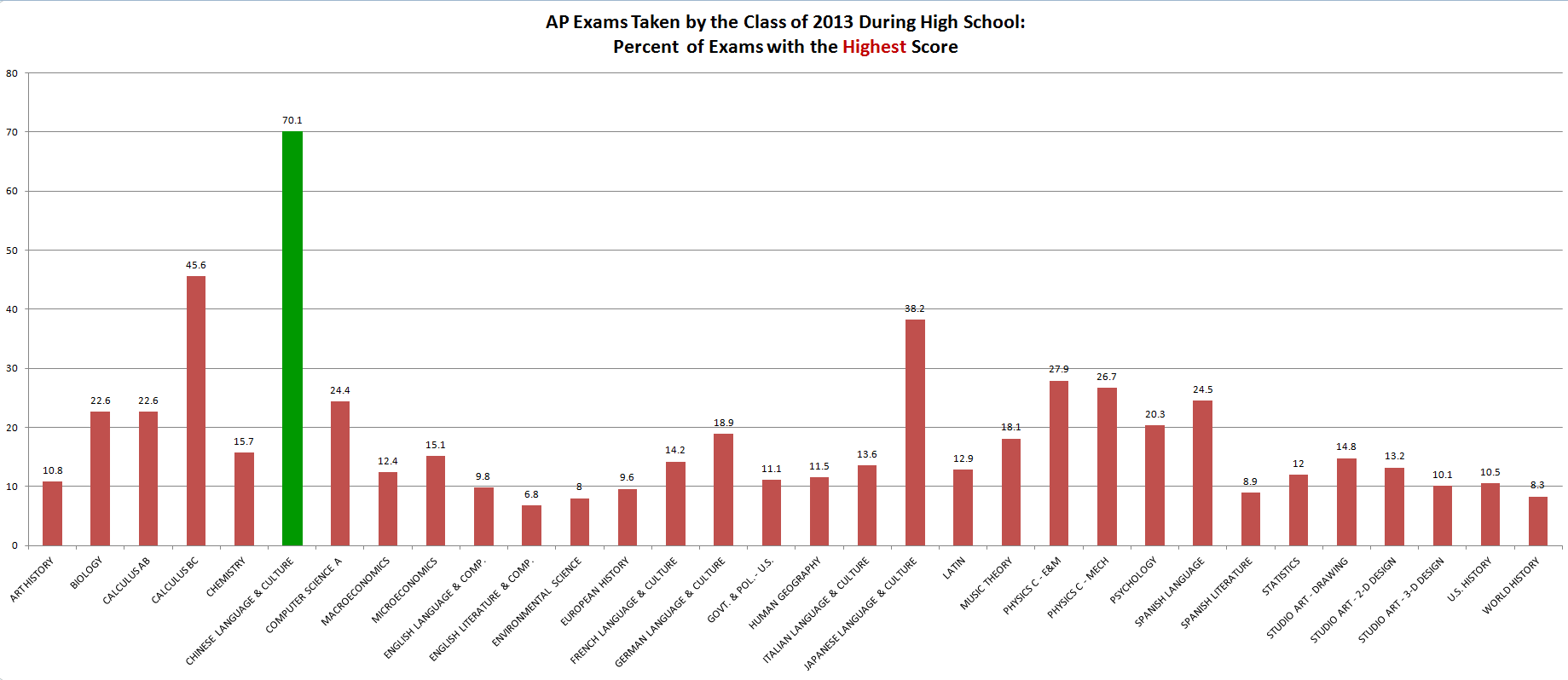

The results of the Advanced Placement exams from the College Board can give us an idea of what’s going on with the teaching of Mandarin Chinese in U.S. high schools.

As the charts below demonstrate, there’s something very different about the scores for the AP exam in Chinese Language and Culture compared with the scores for just about everything else.

The tests are graded on a five-point scale, with a 5 being the top score. Generally, a 3 is considered a pass, though some universities choose to give or deny credit based on different scores.

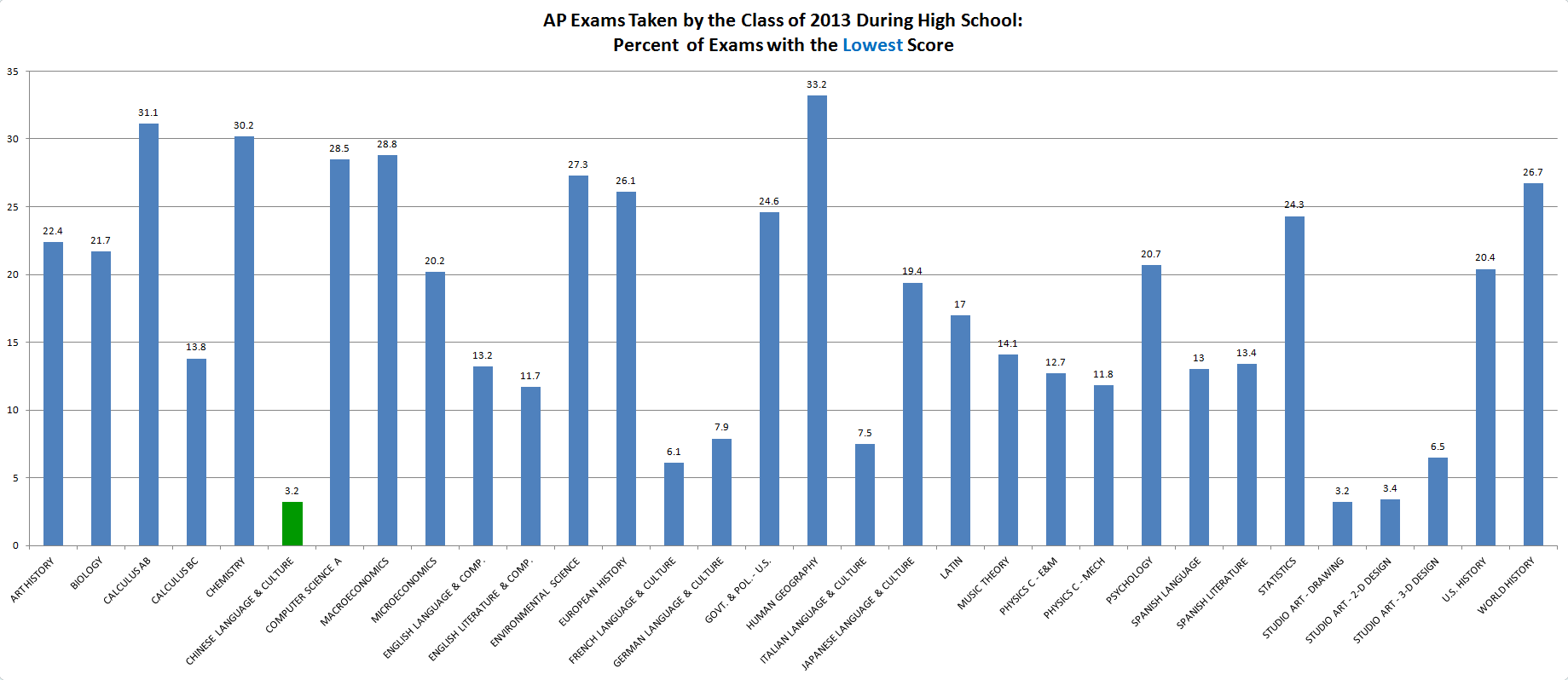

The first chart shows the percentage of of test takers who received a score of just 1 (lowest) on their respective AP exams. The median of the figures below for the percentage of test takers who received the lowest score is 18.2. The figure for Chinese (in green, at 3.2) is just 0.18 times that. Studio Art Drawing and Studio Art 2-D Design are at about the same level here as Chinese Language and Culture. But everything else is at least twice that — in most cases many times that.

AP Exams Taken by the Class of 2013 During High School: Percent of Exams with the Lowest Score

(click any chart to enlarge it)

So, relatively speaking, almost no one received the lowest score on the AP Chinese Language and Culture exam.

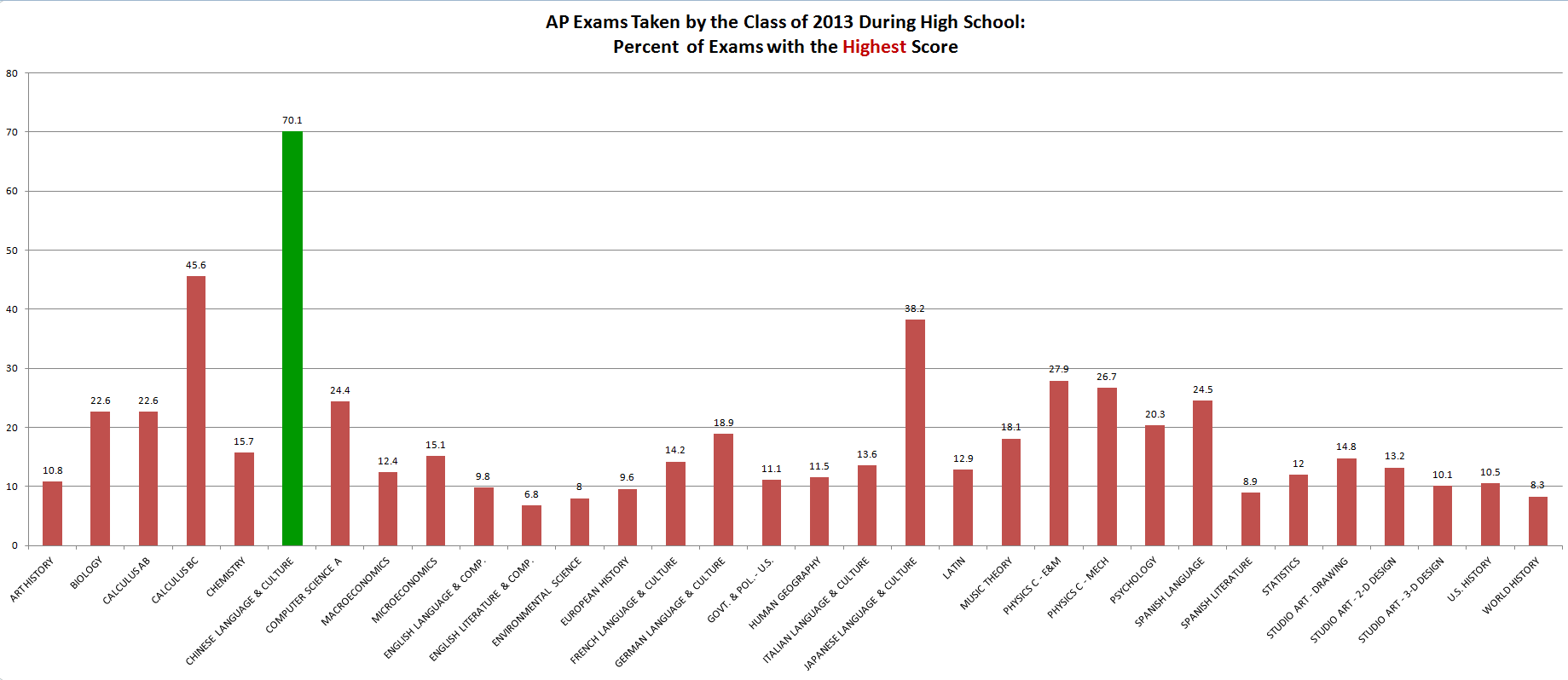

What about the highest score? The median of the figures below for the percentage of test takers who received the highest score (of 5) on their respective AP exams is 13.9. The figure for Chinese is 5.0 times that.

AP Exams Taken by the Class of 2013 During High School: Percent of Exams with the Highest Score

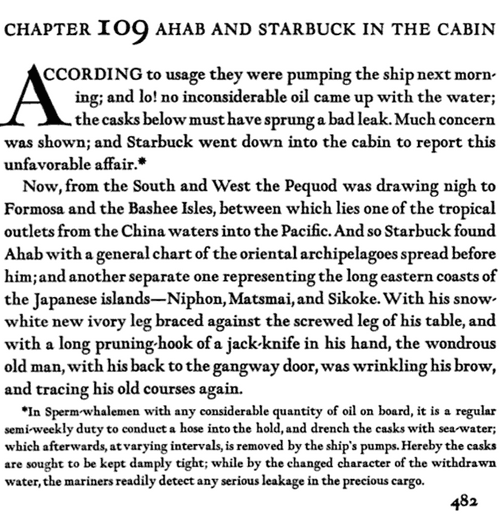

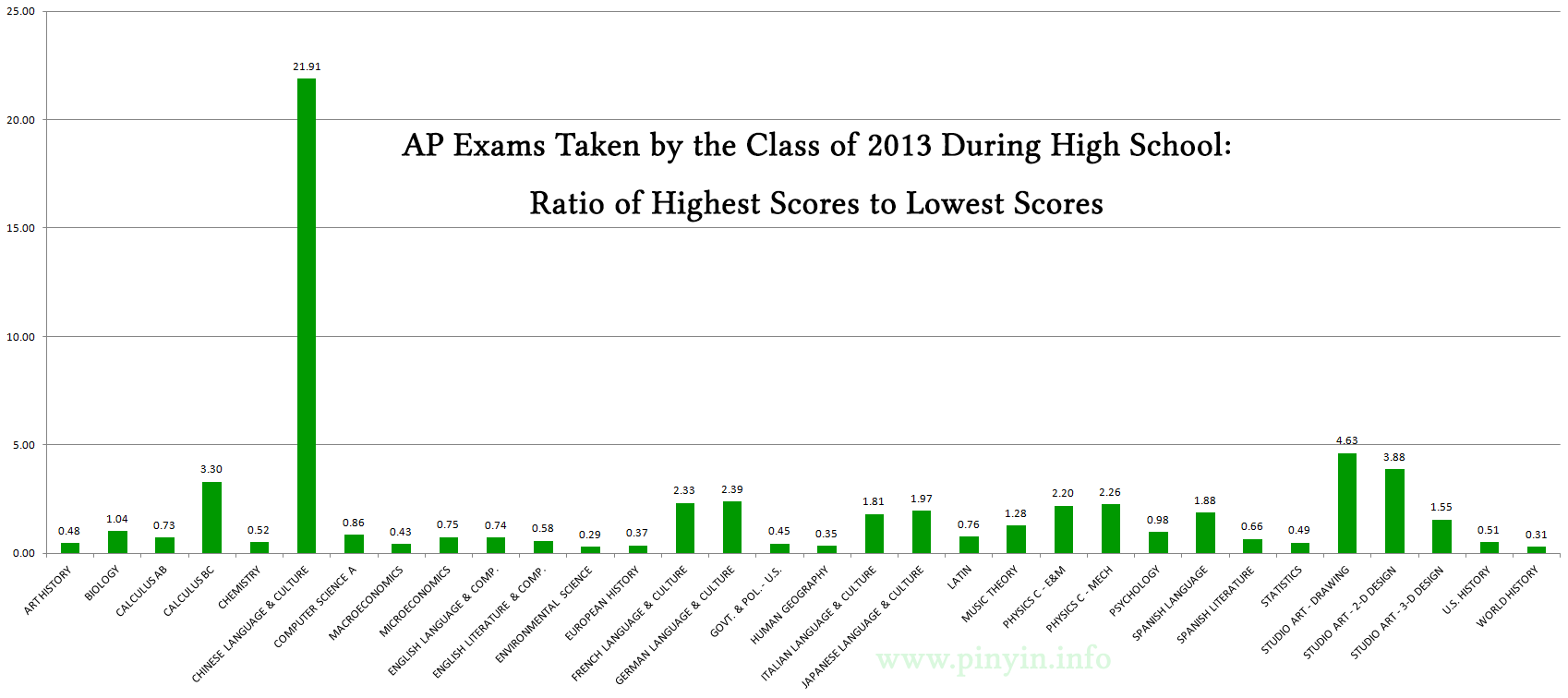

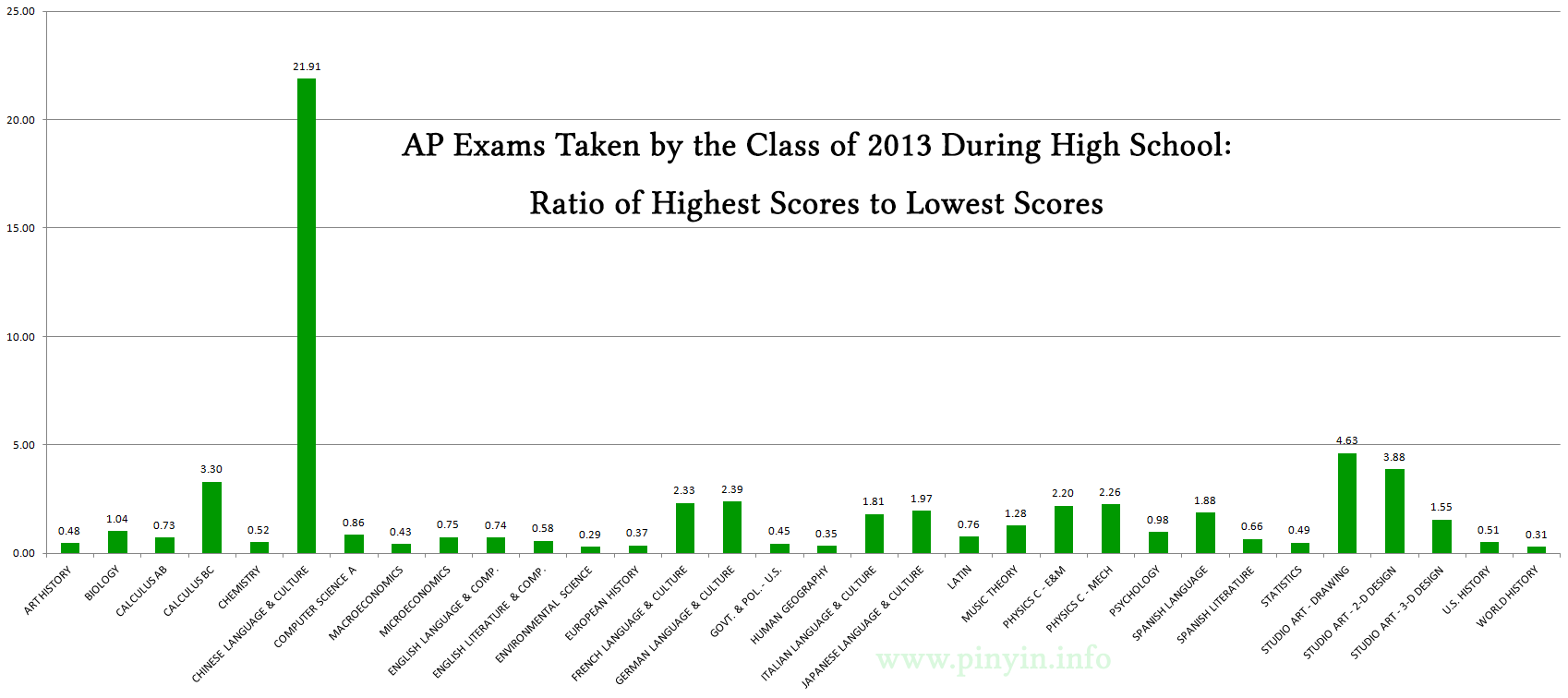

Finally, below is a chart putting the differences into greater perspective. It shows the ratio of highest scores to lowest scores on various AP exams.

The median of the figures below for the ratio of highest scores to lowest scores on the AP exams is 0.8. The figure for Chinese is 27.1 times that.

As is obvious from the image below, nothing else is even close.

AP Exams Taken by the Class of 2013 During High School: Ratio of Highest Scores to Lowest Scores

The reason for this massive difference is that the Advanced Placement exam for Chinese Language and Culture is taken mainly by native speakers and others who generally have not had to learn most of their Mandarin in their high school AP classes. This doesn’t bode well for newcomers to the language who want to learn. But as lopsided as the situation is, things are improving. More on that in later posts.

source: The 10th Annual AP Report to the Nation, February 11, 2014

See also Results of US AP exams: first year for Mandarin, Japanese, Pinyin News, February 14, 2008.