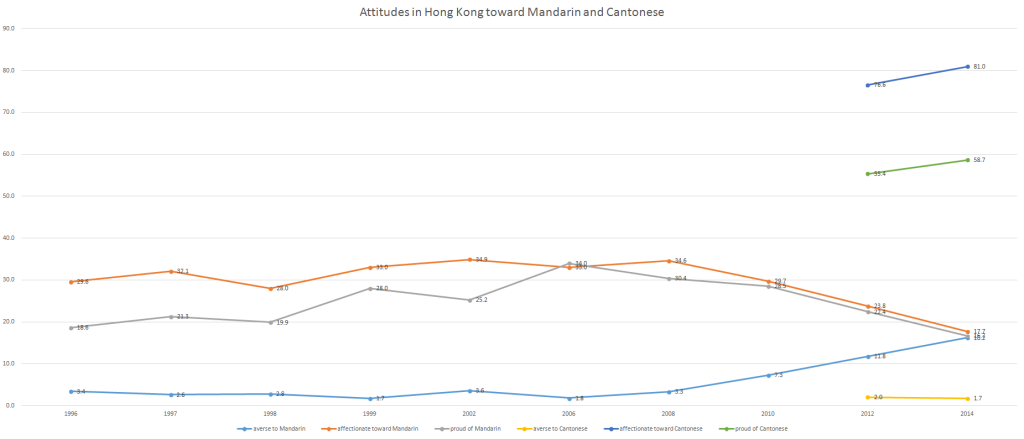

Line breaks are an interesting but little-discussed aspect of typography. That’s a shame, because they can matter, especially in signage.

Book covers are another place where line breaks can matter. I’m especially concerned with those because I’m involved in a company that publishes books about Taiwan, China, and other places in East Asia. I wish I could take credit for Camphor Press’s book covers; alas, though, I have no talent in that area.

Here’s a good example of a line break making a difference in a sign. This ends up being not unlike a typographical crash blossom. I took this photo last week at a Costco in metropolitan Taipei.

For those who are curious, NT$987 is about US$29.60.

Anyway, here’s the Mandarin text:

北海道熟凍毛蟹(冷凍)

Běihǎidào shú dòng máoxiè (lěngdòng)

(I don’t know what that first “dòng” is doing there, given that this ends with “lěngdòng.”)

For maoxie, the ABC Chinese-English Dictionary gives “small crab; baby crab.” But I’m not sure that’s quite right.

If the translator had gone with the more common form of “hairy crab” instead of “hair crab,” the adjective would have alerted readers that they needed to keep going. On the other hand, use of another common translation, “mitten crab,” wouldn’t have helped much, though I suppose that

HOKKAIDO COOKED MITTEN

CRAB

is slightly more palatable sounding than

HOKKAIDO COOKED HAIR

CRAB

And at least they didn’t use the sometimes seen translation of “hair crabs,” which could conjure up altogether the wrong image.

![sign in a Costco seafood section that reads 'HOKKAIDO COOKED HAIR [line break] CRAB'](https://pinyin.info/news/news_photos/2016/02/line_breaks_typography2.jpg)