Since posting about the Pinyin subtitles for Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon and The Story of Stuff I have received several messages inquiring about how someone might make Pinyin subtitles themselves. So I might as well put the answer online.

Although at the present stage of software implementation subtitle conversion isn’t as simple as pushing a button, the process is not particularly difficult, assuming you have a good source text to work from. But this does require some time and the right tools.

The Right Tools

The most important tool is, of course, the one that performs the conversion to Hanyu Pinyin. And it’s crucial to keep in mind that not all Pinyin converters are created equal; in fact, the vast majority of so-called Pinyin converters are best avoided entirely. The world does not need any more texts in the hobbled, poorly written mess that many people erroneously think of as Hanyu Pinyin; but it very much needs texts in real Hanyu Pinyin. So don’t waste your time with a program that doesn’t do a good job of word parsing, etc.

At present the clear front-runner for converting Chinese characters to Hanyu Pinyin texts (real Hanyu Pinyin texts) with a minimum need for user assistance is Key Chinese (Windows and Mac). The demo version is fully functional for 30 days. Key’s considerably less expensive “Hanzi To Pinyin With Tones Conversion Utility” for MS Word texts (also with a 30-day demo) would probably also work well, though I haven’t tried it myself.

Wenlin (Windows and Mac) is another excellent program that can produce properly spelled and word-parsed Hanyu Pinyin. But it requires users to run some disambiguation themselves, which can take a lot of time when you’re talking about something with as much text as a screenplay. Nonetheless, Wenlin’s incorporation of John DeFrancis’s ABC Chinese-English Comprehensive Dictionary makes it a helpful reference when performing post-conversion checks. Also, especially if one does not have Key, Wenlin — even the function-limited but non-expiring demo version — is useful for handling some adjustments (such as removing tone marks or providing a workaround when dealing with programs that don’t handle Chinese characters well).

You’ll also need a Unicode-friendly text editor with good support of regular expressions (to allow wildcard searches). I like Em Editor, which is Windows based. But lots of other programs would work. One could even use MS Word if so inclined.

Finally, having subtitles in an additional language (usually but not necessarily English) is often desirable, not just for others who would use these subtitles but for yourself as you create the Pinyin subtitles. But often the subtitles one may find in Mandarin are not in synch with those in another language. Software can fix this problem. But I don’t have enough experience with this to recommend certain programs over others.

To sum up, the tools I recommend for creating Hanyu Pinyin subtitles are

- Key Chinese

- Wenlin

- EmEditor (or another Unicode-friendly text editor)

- a subtitle synchronizer

Actually, just the first one, Key, is sufficient to produce Pinyin subtitles. But in my experience using a combination of all four programs is preferable.

Now it’s time to get down to business.

The Main Steps

- acquire source-version subtitles

- synchronize subtitle files

- identify names of the movie’s characters (dramatis personae)

- perform initial conversion of subtitles in Chinese characters to Pinyin

- double check the results and perform necessary cleanup

- create additional version without tone marks

- share your work

1. Acquire subtitles for conversion and reference

At present the most useful site for finding Mandarin subtitles written in Chinese characters is probably Shooter. You may need to try searching for your desired title in both simplified and traditional characters. Also, be aware that movies — especially movies not filmed in Mandarin — often have different names in China, Taiwan, Hong Kong, etc.

You may find it useful to look for subtitles in other languages, too. Shooter can be useful for that, though you may have better luck finding English subtitles at Opensubtitles.org or similar English-language sites.

One can often find different subtitle files for the same movie, so you may wish to examine more than one for quality. Another thing that’s worth keeping in mind: Converting from traditional Chinese characters to simplified Chinese characters is less problematic than vice versa.

2. Synchronize subtitle files

Once you have the files, you should synchronize them with each other according to the directions for the particular program you are using.

If the program you’re using for this chokes on Chinese characters, though, you’ll need to take a couple extra steps. First, convert the Chinese characters to Unicode numerical character references using either Pinyin Info’s NCR conversion tool or Wenlin (full or demo version). The reason for this is that even synchronizers that screw up “李慕白” should be able to handle the NCR equivalent: “李慕白”.

In Wenlin,

Edit –> Make transformed copy –> Encode &#; [decimal]

Take the NCR text and synchronize the files. After you get this taken care of, reconvert to Chinese characters.

In Wenlin,

Edit –> Make transformed copy –> Decode &#;

3. identify names of the movie’s characters

You must teach your software know which strings of Hanzi represent names. For example, it’s crucial for clarity that the character name “李慕白” is written “Lǐ Mùbái” rather than as “lǐ mù bái“. This part takes some time up front. But do not skip this step, because it is not only crucial but will save a lot of trouble in the long run.

Before doing this, however, people may want to refamiliarize themselves with Hanyu Pinyin’s rules for proper nouns (PDF). Note especially what is supposed to be capitalized and what isn’t.

The Mandarin version of Wikipedia is one resource that can be helpful in identifying the names of at least the main characters in the movie. But you’ll want to look for more names and forms than will be listed there. Keep in mind that characters aren’t always addressed by their full names. You need to look for other forms as well (e.g., in Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon Li Mubai is sometimes referred to as “Li Mubai” but other times as “Li ye” or simply as “Mubai”) and enter them.

English subtitles can be very useful for locating most proper nouns in the text. (Hooray for word parsing and capitalization of proper nouns!) The following search of an English subtitle file should help pinpoint the location of proper nouns.

find (with “Match Case” and “Use Regular Expressions” checked):

[^\.]\s[A-Z][a-z]

in MS Word, find (with “Use wildcards” checked):

[!\.] [A-Z][a-z]

Since you’ve already synchronized your subtitles, you’ll easily be able to find the corresponding point in the Mandarin subtitles by looking at the time the line appears.

As you gather the names, or after you compile the full list, add your findings to the Pinyin converter’s user dictionary. In Key, perform Language –> Add Record, then fill in the Hanzi and Pinyin fields.

4. Perform initial conversion to Pinyin

OK, I know you’re eager to run the conversion and see all of those Hanzi turn into lovely Hanyu Pinyin. But there’s one quick step you need to do first. If you’re using Key Chinese, the program won’t make use of all of those character names you just painstakingly added to the user dictionary unless you first run “linguistic reconstruction” on the subtitles you wish to convert:

Language –> Linguistic Reconstruction

Now you’re ready for the big step:

Language –> Convert to Pinyin

5. Double check the results and perform necessary cleanup

Unfortunately, most Pinyin converters — even the best — tend to be lazy about inserting spaces in some of the places they belong, such as around numeric and alphabetic strings. For example, “自3月22日(星期一)起至5月31日(星期一)” will generally convert to something that looks like this:

“zì3yuè22rì (Xīngqīyī) qǐ zhì5yuè31rì (Xīngqīyī)”.

But it should look like this:

“zì 3 yuè 22 rì (Xīngqīyī) qǐ zhì 5 yuè 31 rì (Xīngqīyī)”.

To fix this in your Pinyin text, run the following regular expression in EmEditor. Make sure “Match Case” is not checked.

find:

([a-zāáǎàēéěèīíǐìōóǒòūúǔùǖǘǚǜ])([0-9]+)([a-zāáǎàēéěèīíǐìōóǒòūúǔùǖǘǚǜ])

replace:

\1 \2 \3

If you do this in Word, you’ll need to use the following instead in your wildcard search.

find:

([A-Za-zĀÁǍÀĒÉĚÈĪÍǏÌŌÓǑÒŪÚǓÙǕǗǙǛāáǎàēéěèīíǐìōóǒòūúǔùǖǘǚǜ])([0-9]{1,})([A-Za-zĀÁǍÀĒÉĚÈĪÍǏÌŌÓǑÒŪÚǓÙǕǗǙǛāáǎàēéěèīíǐìōóǒòūúǔùǖǘǚǜ])

replace:

\1 \2 \3

The rest of cleanup work usually involves you simply reading through the text, looking for errors, perhaps while listening to the movie.

6. Create additional version without tone marks

If you have Key, this is very easy: Highlight the entire text, then

Format –> Strip Tone Marks.

And you’re done, though because Key keeps u-umlaut as such, if your television or other device doesn’t show the letter ü correctly you may wish to convert “ü” to “v”.

If you don’t have Key or access to another program that can do the same thing as easily, then use a combination of Wenlin (again, even the demo will do what you need) and a text editor. First, paste your Pinyin text into Wenlin. Then select all of the text and perform

Edit –> Make transformed copy… –> Replace tone marks with 1-4

Copy and paste the results into a new document in your text editor. Then run the following search-and-replace. Make certain the “Use Regular Expressions” or “Use Wildcards” box is checked.

find:

([A-Za-z])([1-4])

replace with:

\1

Then click “Replace All”.

What this looks like in EmEditor:

What this looks like in MS Word:

7. Share your work

It’s much better if people can concentrate on producing new material rather than having to redo things others have already taken care of. So if you make a good Hanyu Pinyin version of something, please let me know.

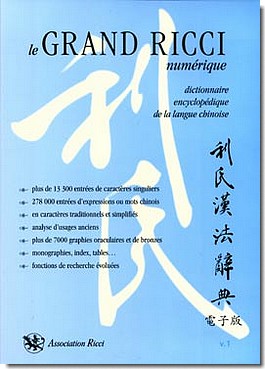

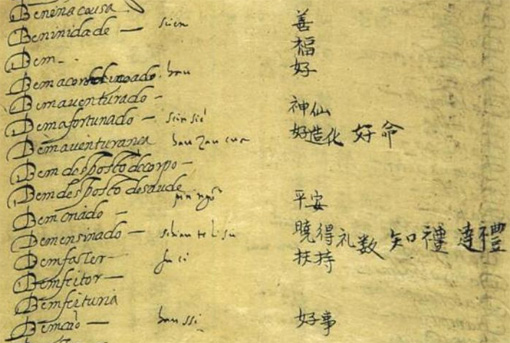

The magnificent Grand dictionnaire Ricci de la langue chinoise, better known as

The magnificent Grand dictionnaire Ricci de la langue chinoise, better known as

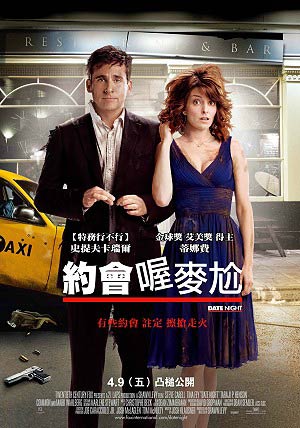

In Taiwan, the new movie Date Night has been given the Mandarin title

In Taiwan, the new movie Date Night has been given the Mandarin title

A review in a

A review in a