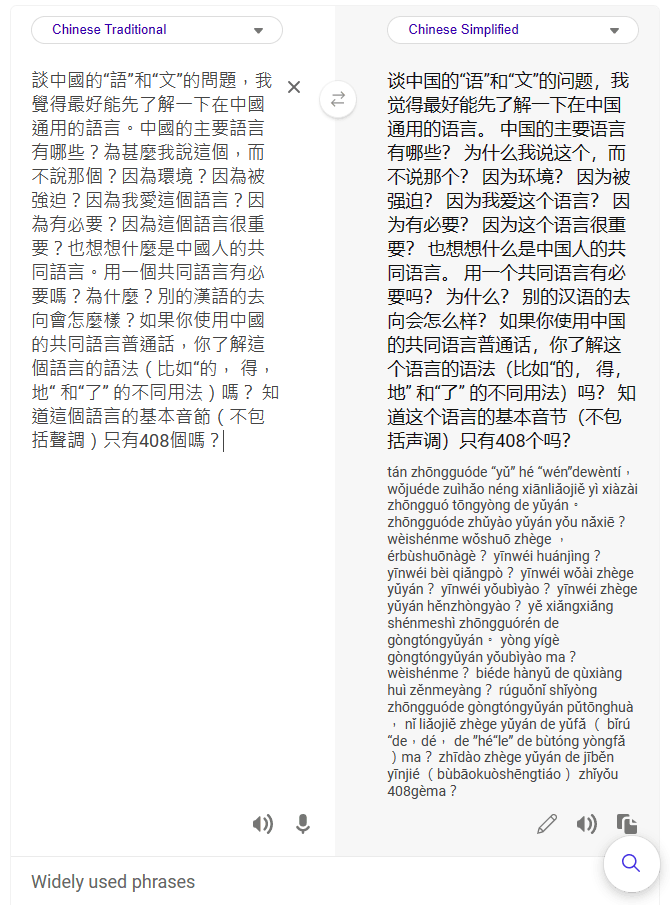

For the past few months, one can occasionally spot trains along the Taipei MRT’s blue line (aka the Ban-Nan line, for the Banqiao–Nangang line of the subway system) sporting a new style of above-door announcements. (Perhaps some of the other lines have these as well; but I’m not on them as much and haven’t spotted new signage on those yet.)

The MRT has signs above the doors to let people know what the stops are coming soon. Or at least that’s what the signs are supposed to do, what they need to do in order to help passengers. Alas, that crucial function appears to have been overlooked when designing the new signs, which are all bling-bling and little useful substance.

In fact, they’re so bad that I’m almost surprised they don’t feature cutesy cartoon characters — something that would make the disaster complete.

The photos in this post of the new signs were taken from the seat with the best vantage point of the video-screen sign. Some zoom was used to get the important part of the image to stretch from one side to the other of the photos. In short, the parts of the sign passengers need to read likely appear even smaller in real life than they may look in the photos. Of course, I could have positioned myself immediately in front of the signs and gotten better photos. But the point of signage isn’t what can be seen if one is standing close to and directly in front of it; rather, good signage needs to work for viewers from farther away and at an angle as well. So the proximity and angle represent a compromise on my part rather than the farther vantage point from which many riders will experience the signs. In other words, for many riders, the signs will look even smaller and less clear than shown in these photos.

And, as we’ll see, smaller is definitely not a good thing.

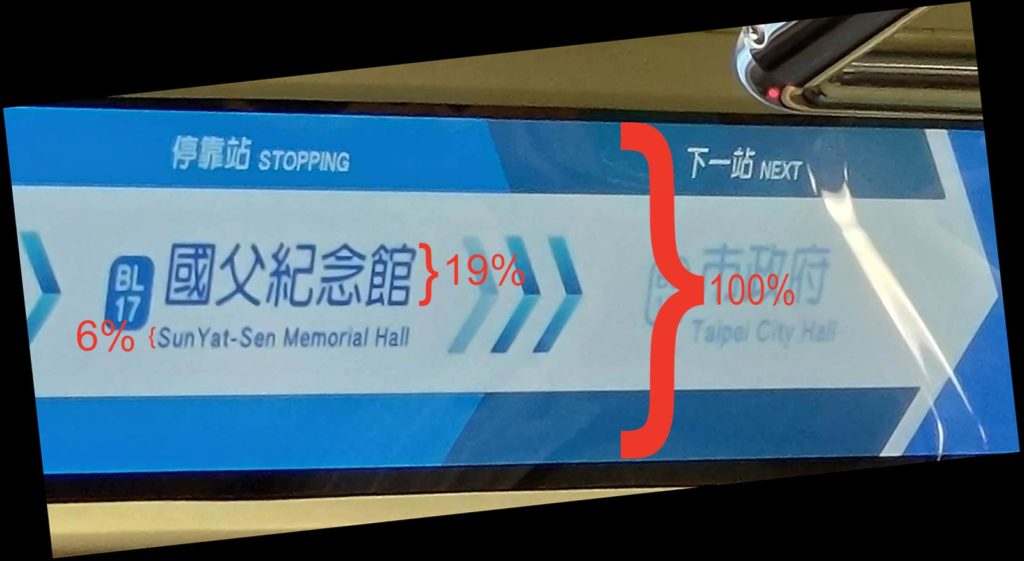

Here’s a close-up of the above sign, rotated slightly and showing the size of the text as a percentage of the screen height (approximately).

The screens themselves are large. But what about the information they need to convey? The names of the stations, the most important information, are small: just 19% of the screen height for the Chinese characters and only 6% of the screen height for the Pinyin. I suppose one could add another percentage point or even two if the descenders are counted as well rather than just the cap height. But even 8% would be utter madness! The Pinyin text is absurdly tiny — and as such is close to useless. How is anyone supposed to read that?! But there’s plenty of space on the screen to make the Pinyin larger, especially if it is given separately rather than in combination with Chinese characters at the same time.

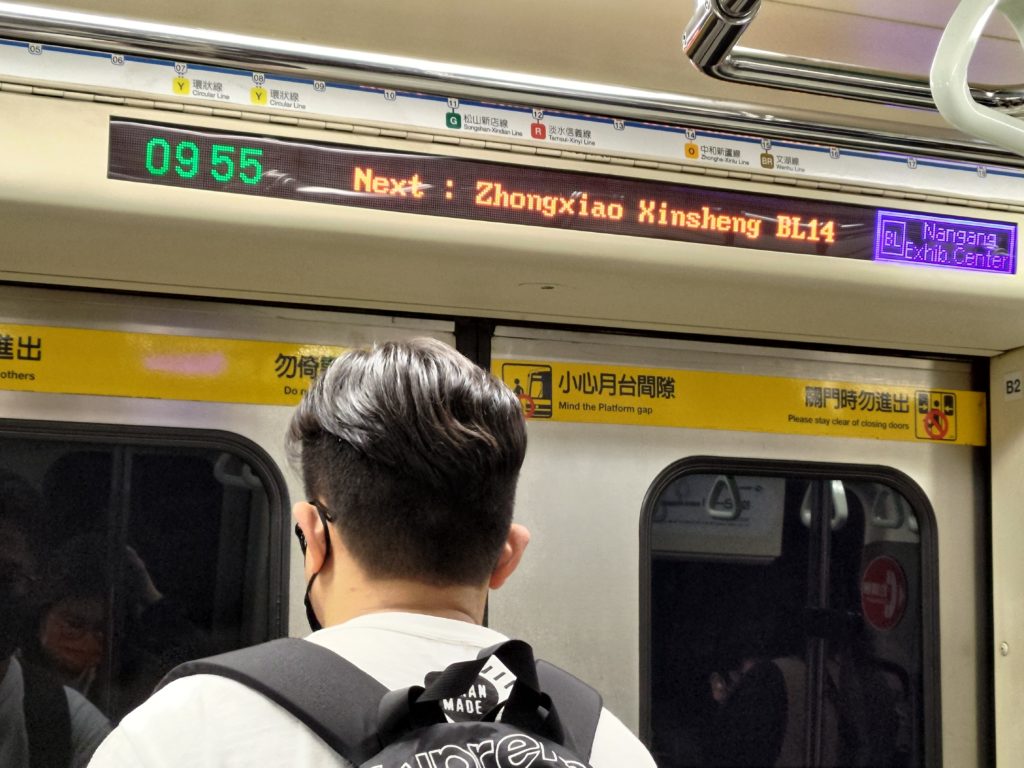

The video screens do cycle through different information, with one screen providing station names in Pinyin and English without any Chinese characters. But it’s almost as if they’re trying to make the signage unreadable. Here’s an example:

Again, the English/Pinyin names are too small to read — needlessly so. And it doesn’t help the cause of making text large enough to read that the Taipei MRT has some needlessly wordy station names.

But there is one new feature I actually like: listing how many minutes before the next stations. (Note the numbers along the bottom right of the screen.) This is nicely done — if only one could read the names of the stations.

And still more space could be saved if those nicknumbers (e.g., “BL17”) were removed. I have yet to hear anyone ever even mentioning them, at least not in a positive way. And to think the MRT system spent NT$300 million (about US$10 million) on that!

And let’s not forget that Taiwan is projected to become a super-aged society by 2025 — which means an especially large number of people who don’t see as well as they used to. Thus, it is all the more important that the letters are large enough to be read by people with less than perfect eyesight.

Alas, there’s more. The signs, as bad as their design is from the standpoint of the size of the text, have another significant flaw: their use of color.

Look at how the name of the next station is presented: in light-blue-gray against an off-white background. There is little contrast between the text and the background, which makes the text very difficult to read. I would have thought that this problem, like the problem of size already discussed, would have been painfully obvious to everyone involved in the design process. Yet for some reason this wasn’t corrected long ago on the drawing board but has instead made it all the way to signage on the MRT itself! That light-blue-gray against off-white makes me just livid.

Another important aspect of color for the MRT is the assignation of colors to the different transit lines. Identifying different lines by color is actually quite useful, and many people refer to the various lines by their color. So how well do the new signs handle this? If you’re familiar with Taipei, try to ignore the names and placements of the lines for the moment. Just this once — because the actual station names are so tiny and damn hard to read on these video screens, and because I’m hoping you’ll try to let your knowledge of the MRT avoid interfering with your objective judgment on this — I’m asking you to refer to the numbers for Taipei MRT stations, stupid though they are.

The lines that intersect with the blue line are marked by vertical bars of color. OK, now look at the image below and answer a few simple questions. You’ll probably have to click on the photo one or more times to achieve the extreme magnification needed to view the sign well.

Q: Which station or stations intersect with the red line?

A: BL12.

OK, that was easy. Now another.

Q: Which station or stations intersect with the green line?

A: BL11.

Simple enough. But how about these?

Q: Which station or stations intersect with the brown line?

Q: Which station or stations intersect with the orange line?

Q: Which station or stations intersect with the yellow line?

Why the MRT thinks passengers need a regular reminder of what car number they are in is beyond me. Note, too, how those numbers are larger than the station name in English/Pinyin.

The answers are, respectively, BL15 & BL23, BL14, and BL07 & BL08.

How’d you do? And could you even tell that BL15 and BL23 are supposed to be the same color, and that color is supposed to be brown?

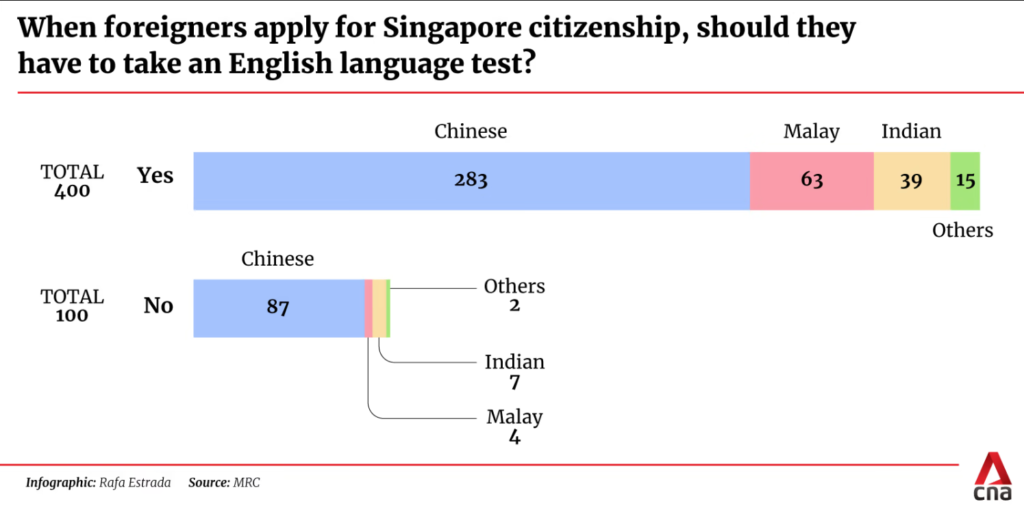

Here’s a look at what the current/old signage looks like.

- The style is basic but effective.

- The letters are large enough to read.

- The space before the colon is wrong.

- The contrast between the color of the text and the color of the background is strong, making the text easy to read.

- The addition of “BL14” is an unfortunate distraction (sometimes less is more); but it’s nothing that the new signs don’t repeat.

In short: By the most important measures, the old signs are better than the new ones. And they already exist, so keeping them won’t cost taxpayers and farepayers anything, unlike putting in expensive new video screens that make navigating the MRT worse.

Meanwhile, the MRT system has still not corrected errors in the Pinyin for the names of some stations.