Studying kanji while taking in a Japanese noh drama — what could more exciting? Heh.

A common problem for those new to Japanese traditional performing arts is that–even for native Japanese speakers–it is hard to understand the story and old-fashioned language used in noh recitation or gidayu, a form of narrative chanting that accompanies bunraku performances. With a view to solving this problem, there has been a marked increase in productions using Japanese subtitles at the National Theatre in Tokyo and National Bunraku Theatre in Osaka. The National Noh Theatre in Tokyo also plans to make greater use of subtitles on screens it will introduce in autumn.

The new computer-controlled system to be introduced at the National Noh Theatre in Tokyo, where prior improvements to seats and other theater facilities are scheduled for completion in August and September, will allow Japanese subtitles to be displayed on flat-panel screens installed in seat backs.

“We will provide Japanese and English subtitles for the time being, although the system will allow us to use four channels in total,” said an official at the noh theater. Noh recitation will be displayed as it is in Japanese, while the plot of the play and a briefing on scenes will be provided in English along with a translation of the recitation….

Some bunraku performers at first questioned why Japanese subtitles were necessary since most audience members are Japanese.

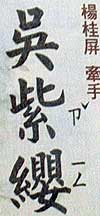

“But they don’t voice such objections any more. Some even say the subtitles are useful in learning kanji…,” said Takemoto Sumitayu, a bunraku narrator and a living national treasure.

The National Bunraku Theatre hopes that the service “will help overcome the image of traditional performing arts as hard to understand.”

I suppose as long as the chairback is below the stage, the text would still be subtitling. But I can’t help but wonder if there’s a more precise term. It’s not likely to be real captioning. And what’s the word for texts that are presented on the sides of stages?

source: Does Japanese theater need Japanese subtitles?, Daily Yomiuri, July 8, 2006

I’ve already written some about

I’ve already written some about