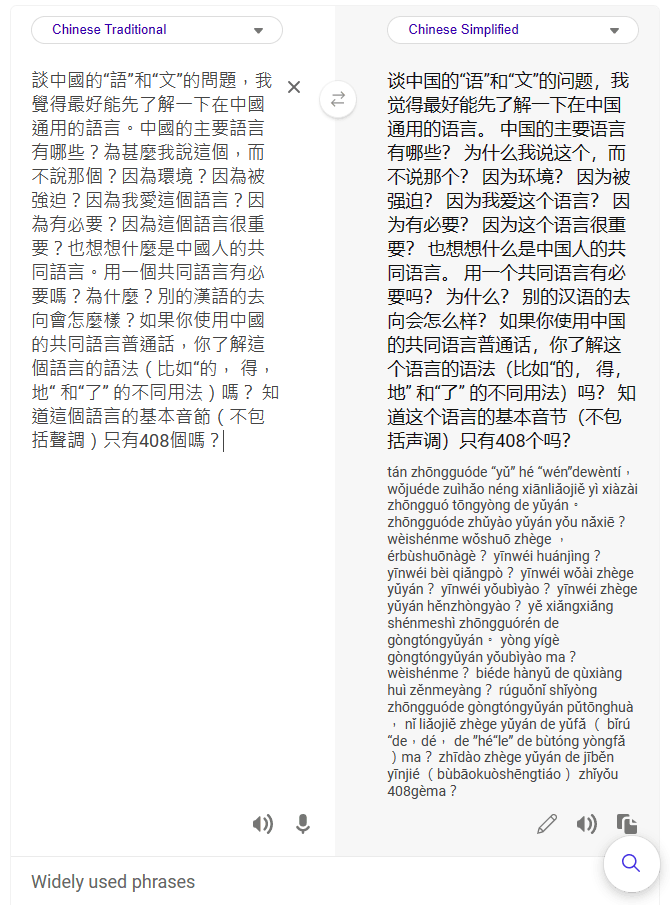

My post about a month ago on another pun for the Year of the Rabbit was in part an excuse for me to note how common “OMG” (oh my God) has become in Taiwan. Indeed, it should be considered not just English anymore but a frequently used loan word, one that is usually written, using the Roman alphabet, as a “lettered word” in Mandarin (i.e., “OMG“). But sometimes “oh my God” shows up in Chinese characters (e.g., 喔麥尬) used as phonetic approximations of the English. And sometimes, as in today’s pun-tastic example, it appears in a mix of English and Chinese characters.

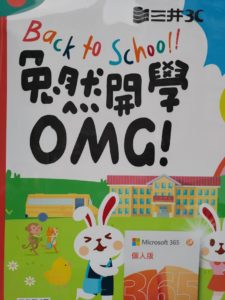

Oh.my.軋

The “Oh.my.軋” store sells nougat, as one can see from the smaller sign below and to the right of the main sign: “鮮治牛軋糖” (xiān zhì niúgátáng / freshly made nougat).

Niugatang is simply a Mandarinization of the English word nougat; it’s transcribed “牛軋糖”. Tang is the Mandarin word for sugar and thus a short form meaning candy.

The use of a stylized version of the character for niu (牛), which rhymes with English’s “oh”, inside the “Oh” of the logo also makes the sign not just Oh my ga but also niu my ga (牛.my.軋). Puns upon puns.

The “Oh.my.軋” uses the ga from niugatang as a phonetic approximation of the English word “god.”

The character “治” is also worthy of note as an example of why Chinese characters are so damn hard. The character has two main parts. The left side has 氵, which is an alternate form of “水,” which is used in writing “shuǐ” (“water”) and many other words. The right side is 台 (tái), which is used in writing the word for platform but which is most commonly seen in Taiwan used phonetically in place names: Taiwan, Taipei (Taibei), Taichung (Taizhong), Taitung (Taidong), etc. So in terms of sound, that’s a shui and a tai. But in this case the phonetic hint commonly given in Chinese characters is 台 (tái). So does that mean the character “治” is pronounced tái?

Nope. Note even close. It’s pronounced zhì. And one just has to memorize such instances.

If you’re thinking, Hmm, shui plus tai? That’s water plus platform. Maybe the character is an ideograph for a pier! Nope. Once again, not even close. That’s generally not how Chinese characters work, no matter how many BS-filled TED talks on Chinese characters, memes, and crisis-tunity claims fill the Internet.

Of course, a character used for pier would make no sense on a sign for nougat. But as we’ll see, there are other things that don’t make sense here.

As I noted above, “xiān zhì niúgátáng” means “freshly made nougat.” But the weird thing is the character being used for zhì isn’t the “right” one. The sign uses “治” rather than the proper and homophonous “製” (zhì). The character used in the sign, however, doesn’t mean “made” but is instead most often seen in terms like zhìlǐ (治理), which is the Mandarin word for manage/administer/govern. Freshly administered nougat just doesn’t have much of a ring to it. So why did the company use that? My guess — and it’s just a guess — is that they wanted to evoke “Taiwan” through the 台 (tai) part of the character. (The company’s website — which has plenty of instances of the character 製 — claims that their nougat is one of the most popular purchases by tourists from China.) My long-suffering Taiwanese wife, however, exclaims that I think too much, and she yearns for the day when I find a more traditional hobby than spotting strange signs and asking her to help me understand them.

Rough guide to pronunciation for those unfamiliar with Mandarin or Hanyu Pinyin:

- niu. Imagine the yo in Rocky Balboa’s cry of Yo, Adrian! or Dion’s “Yo, Frankie“; then stick an n in front of it.

- ga. Say the word god, but drop the d.

- tang. With the a as in father, not as in the English word sing/sang/sung.

- zhi. Say the word jerk, but leave off the rk. Some people would keep in the r; but that’s not really a Taiwan thing — except perhaps on International Talk Like a

Beijinger Pirate Day.

Further reading listening:

- Gratuitous yo-free Dion link, because Dion is the man! (of course!): “If I Should Fall Behind,” written by Bruce Springsteen.

Company website: