For quite a few years Singapore has had several choices for those wishing to register Singapore-specific domain names, including .com.sg, .net.sg,, .org.sg, .edu.sg, .gov.sg, .per.sg, and just .sg.

Of those, .sg is a top-level domain (TLD), whereas .com.sg, .net.sg,, .org.sg, .edu.sg, .gov.sg, and .per.sg are second-level domains. This post is mainly concerned with TLDs; but when I’m giving totals I also include .com.sg, .net.sg,, .org.sg, .edu.sg, .gov.sg, and .per.sg but exclude specific domains such as groupon.sg. OK, now back to the post.

Although English is the dominant language of Singapore, it is but one of four official languages there, along with Mandarin, Malay, and Tamil, with Mandarin (along with other Sinitc languages) being the most common of the latter three. Some three-quarters of the city-state’s population is ethnic Chinese, and around half of that group speak Mandarin as the main language in their homes. In addition, for decades Singapore has promoted its campaign to Strike Hard Against Hoklo, Cantonese, and Other Languages that Your Government Says Are Puny and Insignificant Because They Have Only Tens of Millions of Speakers Apiece Speak Mandarin.

So you might think that four years ago, when Singapore introduced Singapore’s name in Chinese characters ( ) as a top-level Internet domain (TLD), many in that multilingual society might jump at the chance to pick up some domain names ending with “Singapore” in Chinese characters. (Oh, it hurts me to use images instead of real text there; but until I get the hack fixed, that’s what I’m stuck with.)

) as a top-level Internet domain (TLD), many in that multilingual society might jump at the chance to pick up some domain names ending with “Singapore” in Chinese characters. (Oh, it hurts me to use images instead of real text there; but until I get the hack fixed, that’s what I’m stuck with.)

Let’s take a look at what happened when the gates opened.

In September 2011, the first month that dot-Xinjiapo (. ) domains became available, a total of 86 were registered. That’s not much of a land rush. The next month and the month after that saw no new registrations. But, OK, maybe they had a sunrise period limiting things. What happened later?

) domains became available, a total of 86 were registered. That’s not much of a land rush. The next month and the month after that saw no new registrations. But, OK, maybe they had a sunrise period limiting things. What happened later?

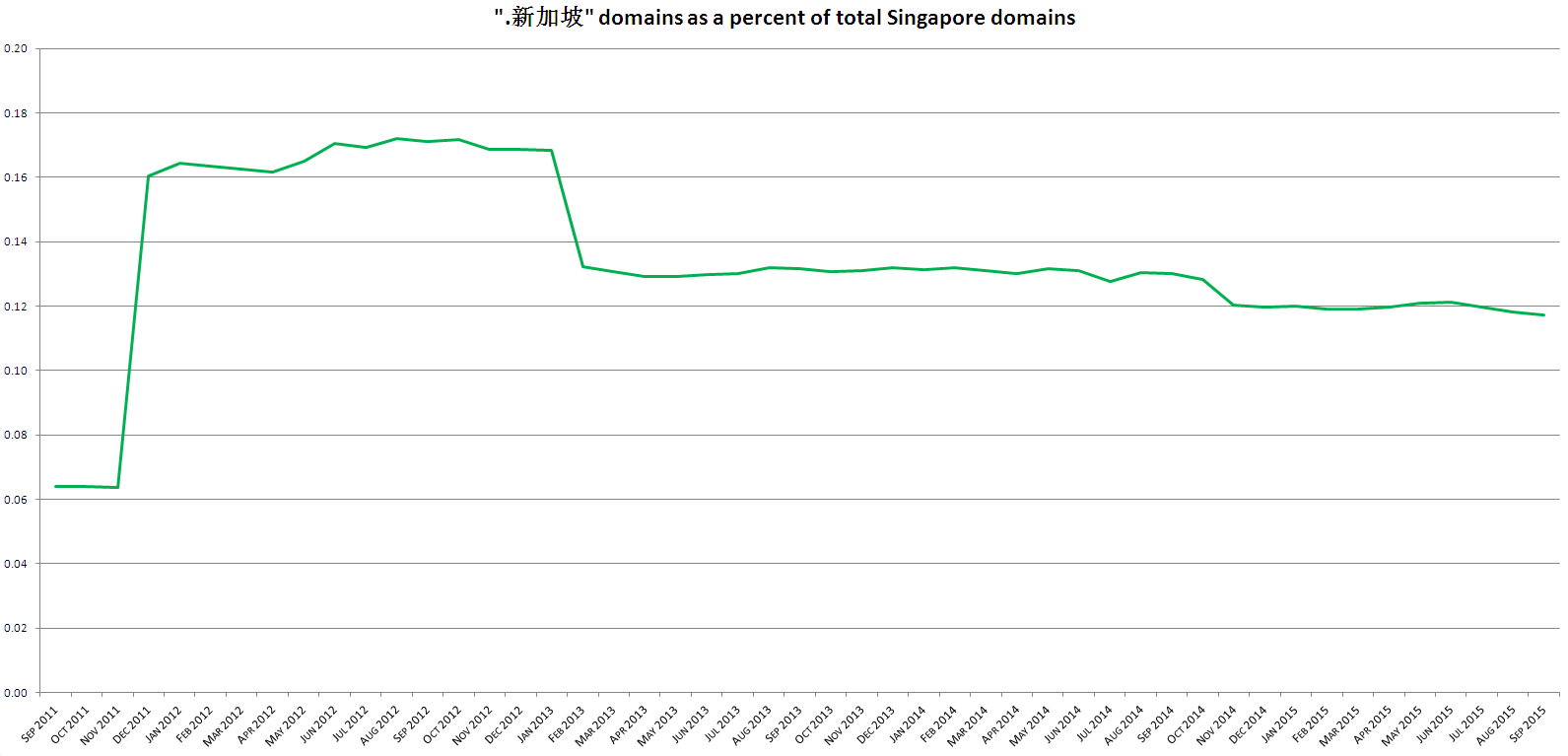

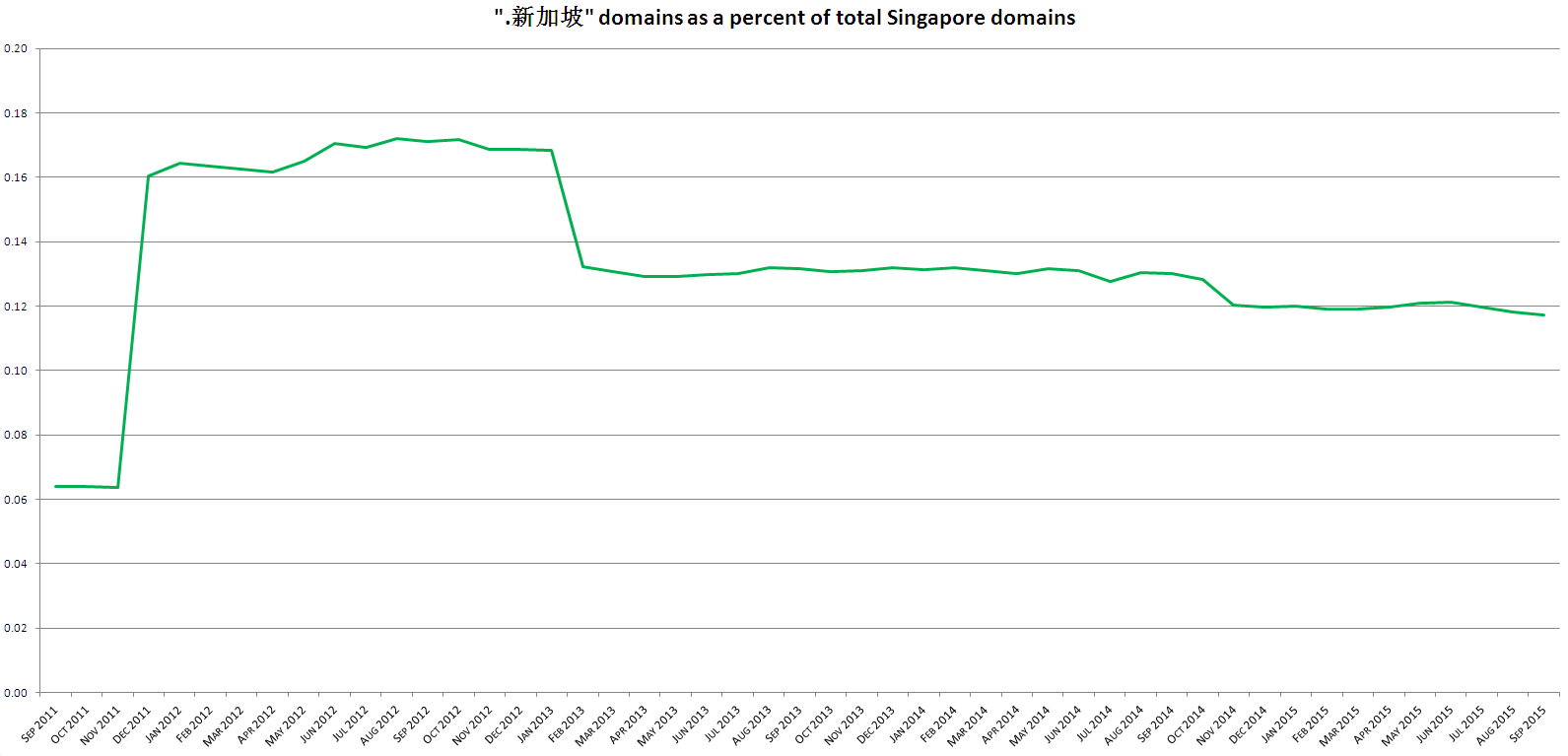

In December 2011 the number jumped to 218. This figure grew over the year 2012 to an all-time high that October of … 247 domains using the . TLD. Just 247. During the same month, Singapore had 143,887 registered domains, meaning that at the high point those with the Chinese character TLD were less than one fifth of one percent of the total. Since then, the number has fallen to a mere 210, with the percentage dropping to less than one eighth of one percent of the total.

TLD. Just 247. During the same month, Singapore had 143,887 registered domains, meaning that at the high point those with the Chinese character TLD were less than one fifth of one percent of the total. Since then, the number has fallen to a mere 210, with the percentage dropping to less than one eighth of one percent of the total.

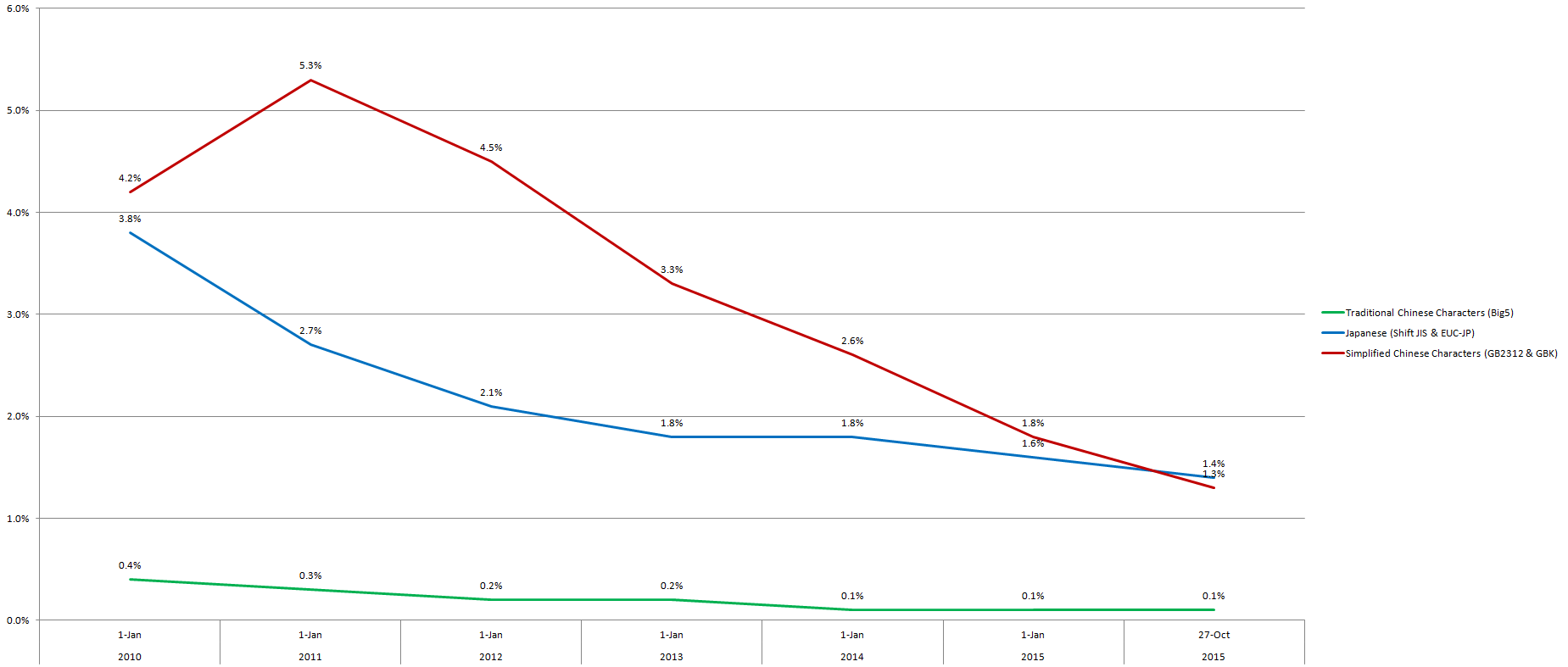

Let’s look at this over time:

A Google search for the . domains reveals that those domains are even less used than the already astonishingly low registration numbers might indicate.

domains reveals that those domains are even less used than the already astonishingly low registration numbers might indicate.

So that’s a total of two active dot-Xinjiapo domains, one of which is for sale. In other words, basically there’s just one being used. Ouch. That’s about as close to utter insignificance as a Singapore TLD can get.

Indeed, the only sort of Singapore-related domain that is of even less interest to the netizens of Singapore is one within the dot-Cinkappur TLD, with Singapore written in the Tamil script:

Dot-Cinkappur (. ) domains have been available since December 2011, which is just a few months after the introduction of dot-Xinjiapo domains. The middle of 2015 saw the all-time record high in dot-Cinkappur domain registrations: sixteen. Since then the number has dropped to just fifteen.

) domains have been available since December 2011, which is just a few months after the introduction of dot-Xinjiapo domains. The middle of 2015 saw the all-time record high in dot-Cinkappur domain registrations: sixteen. Since then the number has dropped to just fifteen.

A search on Google for dot-Cinkappur domains reveals zero active sites.

source: Registration Statistics, Singapore Network Information Centre (SGNIC), accessed October 27, 2015

See also: sg domain names in Chinese characters lag, Pinyin News, June 23, 2010.

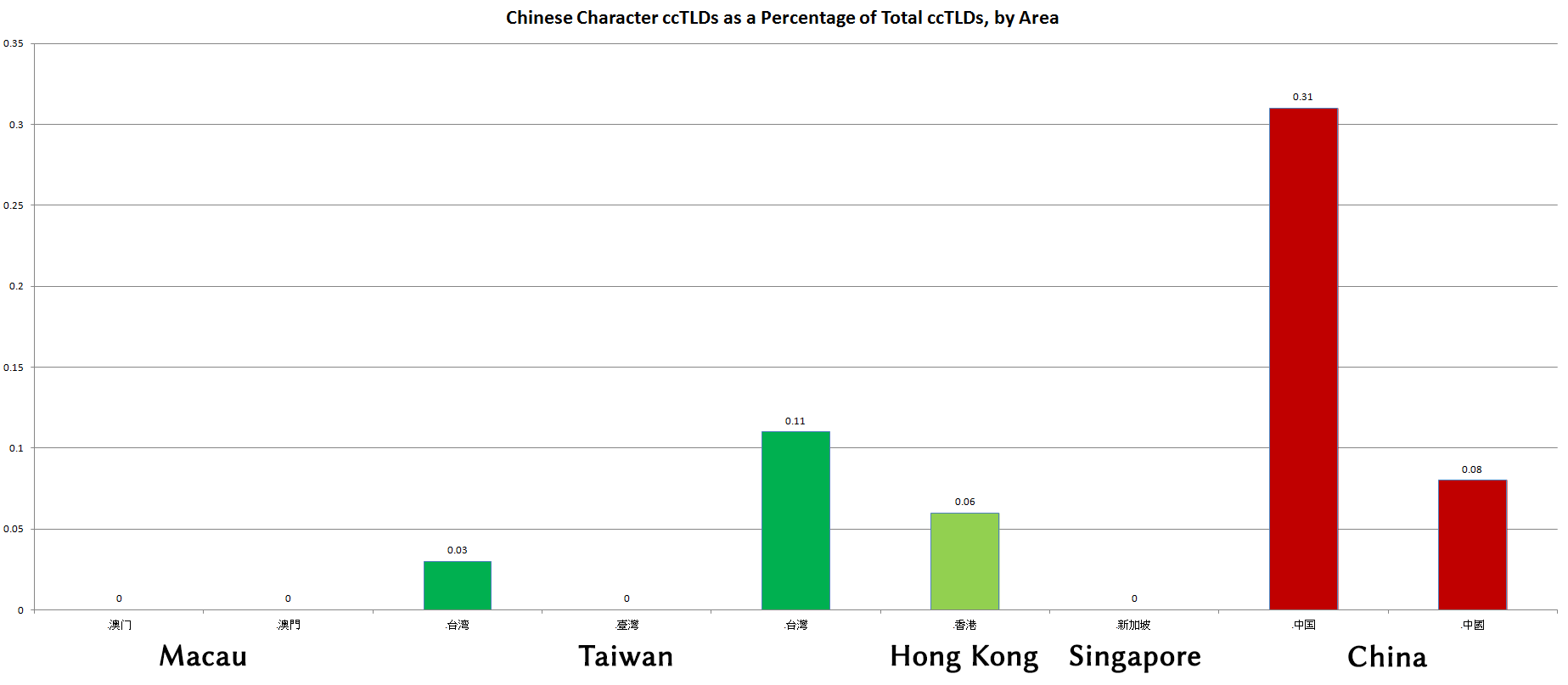

domains compare with the use of .tw domains?

domains compare with the use of .tw domains?  ), so it is omitted here.

), so it is omitted here. and

and  , so those figures are still at zero.

, so those figures are still at zero.  ccTLD, even though the Ma administration, which was in power when Taiwan’s ccTLDs went into effect, officially prefers the more complex form of

ccTLD, even though the Ma administration, which was in power when Taiwan’s ccTLDs went into effect, officially prefers the more complex form of  .

.

) as a top-level Internet domain (TLD), many in that multilingual society might jump at the chance to pick up some domain names ending with “Singapore” in Chinese characters. (Oh, it hurts me to use images instead of real text there; but until I get the hack fixed, that’s what I’m stuck with.)

) as a top-level Internet domain (TLD), many in that multilingual society might jump at the chance to pick up some domain names ending with “Singapore” in Chinese characters. (Oh, it hurts me to use images instead of real text there; but until I get the hack fixed, that’s what I’m stuck with.)