The island known in Mandarin as Lán Yǔ (蘭嶼 / 兰屿) has a lot of different names, including Orchid Island, Ponso no Tao, Pongso no Tawo, Irala, Tabako Shima, Tabaco Xima, Botol, Buturu, Kotosho, and Botel Tobago.

In texts in the roman alphabet, most of the time it’s referred to as “Lanyu.” That’s how I’ve written it in the past. But the Xinhua Pinxie Cidian (p. 21) gives such island names with the yu separate, so I’m going with the Pinyin standard from now on.

Anyway, there are plenty of names for this beautiful place off the southeast coast of Taiwan. But it doesn’t have much in the way of official signs. In large part, that’s because it doesn’t really need many, given the fact that the entire island has only a couple of roads: a ring around the island and another cutting over the mountains, plus a few minor side roads, some not much larger than a sidewalk. It’s not overrun with tourists; and the inhabitants certainly don’t need any signs to tell them where they are or to keep them from getting lost.

Click on any photo for a larger version.

Someone there told me that a long time ago the government assigned some roads the usual crop of Sino-centric names so beloved by the KMT: Zhongshan (i.e., Sun Yat-sen), Zhongzheng (i.e., Chiang Kai-shek), etc. But none of the Yami (Tao) people on the island were in the least bit interested in going along with that and ignored or even removed such signs. (Cars without license plates are also a common site there.)

In one village I found an official sign (but not one for a road) that had been appropriated for part of a wall on someone’s house or shed. This would, of course, have made for a great photo; but circumstances were such that I probably couldn’t have taken the shot without seeming disrespectful, so I passed the opportunity by.

I saw no trace of any official street signs. And even unofficial street signs were few and far between. (See the signpost image near the bottom.)

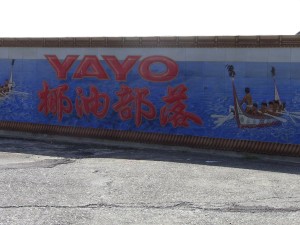

“Yehyu” and “Hungtou” are both in Wade-Giles. These would be Yēyóu Cūn and Hóngtóu Cūn in Hanyu Pinyin (and Tongyong Pinyin and MPS2 — though with the tone marks indicated differently) — for the Mandarin version of the name.

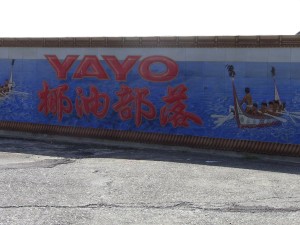

But Yayo appears to be the Yami name.

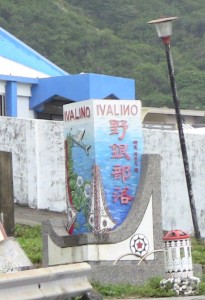

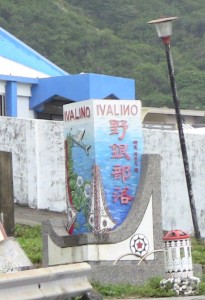

The sort of marker shown below is fairly standard. Note that the name in roman letters (Ivalino) is not a romanization of the Mandarin form (Yěyín Bùluò / 野銀部落). Note also the backward N, which is a mistake, not a special letter.

This photo perhaps best captures the nature of signage on Lan Yu — when there is any signage to be seen, that is.

I was saddened when I was there to hear children speaking only Mandarin with each other rather than the Yami language. But perhaps those I heard weren’t a representative sample.