Reader Jens Finke recently came across a newspaper clipping from about twenty years ago, the dark ages of Taipei’s street signs. Back then most roads in the city were identified in bastardized Wade-Giles and wildly misspelled variations thereof. Two or even more spellings for one name at the same intersection was not uncommon. (Outside of Taipei, many signs were in MPS2, which is often mistaken — including in the article below — for the Yale system.) And so the foreign community of Taiwan by and large cried out for the use of Hanyu Pinyin. But that’s not what foreigners got. Instead, Taipei Mayor Chen Shui-bian decided to go with a half-baked local invention called Tongyong Pinyin.

Really, half-baked. Incredibly, not long after street signs started to go up in this system in 1998, its creator changed it. For example, the article mentions “Zhongsiao” (“Zhongxiao” in Hanyu Pinyin). Scarcely had the paint dried on the new street signs than the spelling in the supposedly same system was changed to “Jhongsiao.” This and other changes rendered most of the new signs obsolete.

But before many signs went up in the old new system or the new new system, Chen lost his December 1998 reelection bid. His successor, Ma Ying-jeou, didn’t pursue Tongyong Pinyin. Ma even took the surprising step of asking foreigners what they wanted and took action to implement the overwhelming choice of the foreign community (both then and now): Hanyu Pinyin, though unfortunately the road to this was not without monumentally foolish detours, bad ideas, and still-unfixed errors.

In 2000, Chen was elected president. He asked his minister of education, Ovid Tzeng, to decide on a romanization system for Taiwan. After Tzeng picked Hanyu Pinyin, he was given the boot. His successor saw the writing on the wall and quickly announced his support of Tongyong Pinyin. Meanwhile, Ma, who remained mayor of Taipei, said he had no plan to change to Tongyong Pinyin. This time marks the beginning of Taiwan’s romanization wars, which raged in the first decade of the century and have still not been completely resolved.

Some readers may suspect the reporter in the article below of pulling people’s legs (e.g., “Special thanks to janitorial assistant Shaw Toe-now of the Jyii Horng Bus Company in Tainan for faxing a copy of his employer’s self-designed romanization table”). But I assure you, it would be very difficult to outdo the craziness of Taiwan’s romanization situation back in those days.

Feel free to use the comments section below if you’d like to share any recollections of Taiwan’s signage mess of the 1990s and before.

In my transcription, I’ve fixed a few typos and omitted the article’s Cyrillic system for Mandarin.

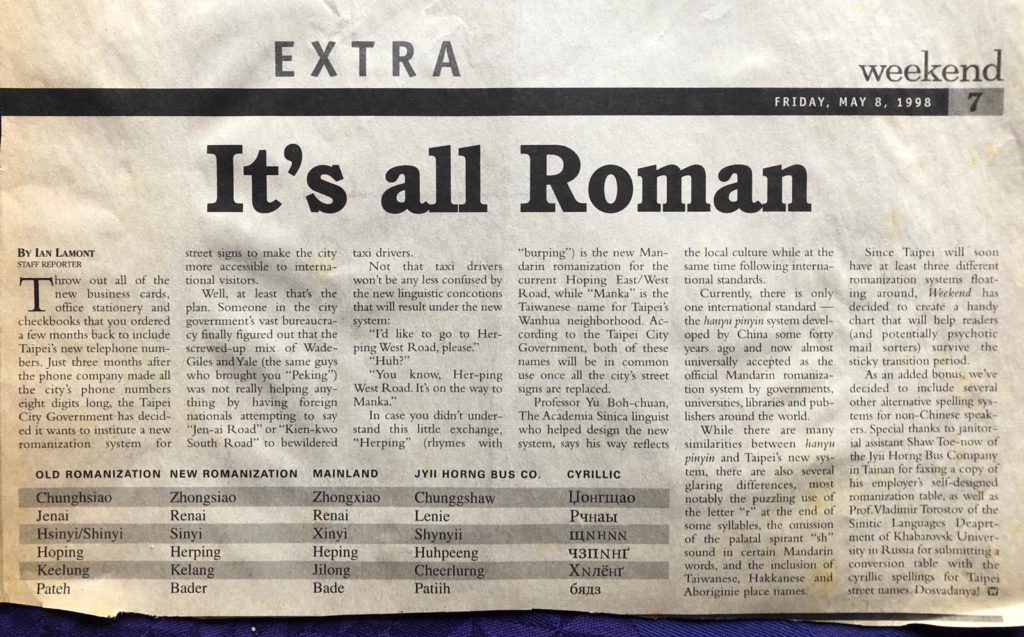

Friday, May 8, 1998It’s all Roman

By Ian Lamont

STAFF REPORTERThrow out all of the new business cards, office stationery and checkbooks that you ordered a few months back to include Taipei’s new telephone numbers. Just three months after the phone company made all the city’s phone numbers eight digits long, the Taipei City Government has decided it wants to institute a new romanization system for street signs to make the city more accessible to international visitors.

Well, at least that’s the plan. Someone in the city government’s vast bureaucracy finally figured out that the screwed-up mix of Wade-Giles and Yale (the same guys who brought you “Peking”) was not really helping anything by having foreign nationals attempting to say “Jen-ai Road” or “Kien-kwo South Road” to bewildered taxi drivers.

Not that taxi drivers won’t be any less confused by the new linguistic concoctions that will result under the new system:

“I’d like to go to Her-ping West Road, please.”

“Huh?”

“You know, Her-ping West Road. It’s on the way to Manka?”

In case you didn’t understand this little exchange, “Herping” (rhymes with “burping”) is the new Mandarin romanization for the current Hoping East/West Road, while “Manka” is the Taiwanese name for Taipei’s Wanhua neighborhood. According to the Taipei City Government, both of these names will be in common use once all the city’s street signs are replaced.

Professor Yu Boh-chuan, the Academia Sinica linguist who helped design the new system, says his way reflects the local culture while at the same time following international standards.

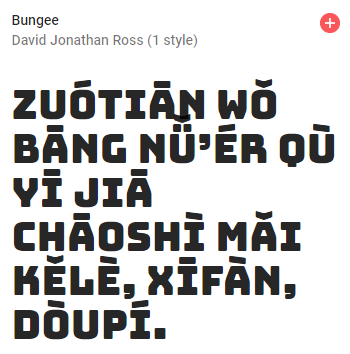

Currently, there is only one international standard — the hanyu pinyin system developed by China some forty years ago and now almost universally accepted as the official Mandarin romanization system by governments, universities, libraries and publishers around the world. While there are many similarities between hanyu pinyin and Taipei’s new system, there are also several glaring differences, most notably the puzzling use of the letter “r” at the end of some syllables, the omission of the palatal spirant “sh” sound in certain Mandarin words, and the inclusion of Taiwanese, Hakkanese and Aborigine place names.

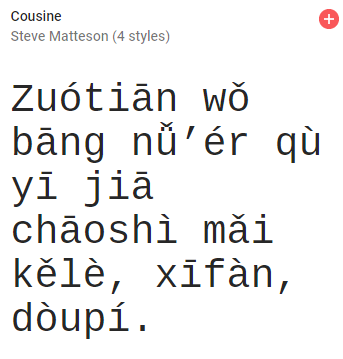

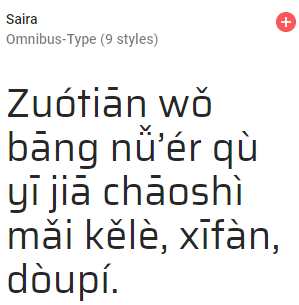

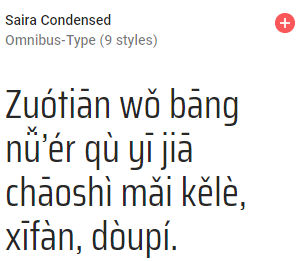

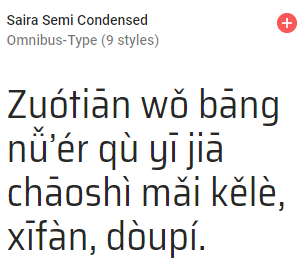

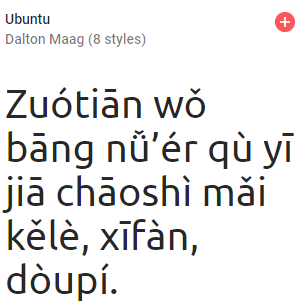

Since Taipei will soon have at least three different romanization systems floating around, Weekend has decided to create a handy chart that will help readers (and potentially psychotic mail sorters) survive the sticky transition period.

As an added bonus, we’ve decided to include several other alternative spelling systems for non-Chinese speakers. Special thanks to janitorial assistant Shaw Toe-now of the Jyii Horng Bus Company in Tainan for faxing a copy of his employer’s self-designed romanization table, as well as Prof. Vladimir Torostov of the Sinitic Languages Department of Khabarovsk University in Russia for submitting a conversion table with the cyrillic spellings for Taipei street names. Dosvidanya!

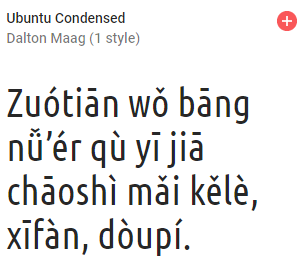

Old Romanization New Romanization Mainland Jyii Horng Bus Co. Chunghsiao Zhongsiao Zhongxiao Chunggshaw Jenai Renai Renai Lenie Hsinyi/Shinyi Sinyi Xinyi Shynyii Hoping Herping Heping Huhpeeng Keelung Kelang Jilong Cheerlurng Pateh Bader Bade Patiih