“No, no, no. It’s spelled ‘Raymond Luxury Yacht,’ but it’s pronounced ‘Throatwobbler Mangrove.’” — Monty Python’s Flying Circus

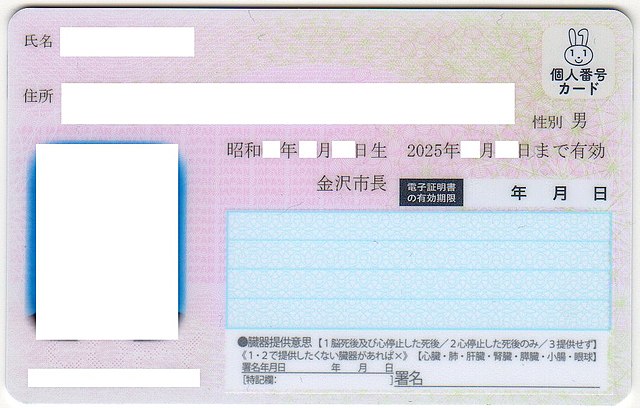

On February 17, Japan’s Legislative Council presented the country’s justice minister with an outline that would mandate that any kanji in names of newborns entered in official family registers include phonetic readings in kana. It would also restrict some readings.

Readings would also be added to names already in registers.

The changes would likely be enforced starting in the 2024 fiscal year (April 1, 2024, to March 31, 2025).

From a news article:

Currently, family registers do not have a field to indicate phonetic readings. After the law revision, family registers will include phonetic readings of kanji in kana characters.

According to the outlines, certain restrictions will be set on “colorful names” whose phonetic readings in kana characters deviate from the original meanings of the kanji characters.

Not only will newborn babies have pronunciations of their names entered in their family registers, but children and adults whose names already appear in family registers will be allowed to add phonetic readings.

Such people will be allowed to register different readings from ones already in their resident registers — records that are distinct from family registers — but the Justice Ministry calls for careful consideration when registering name readings in family registers.

The government plans to submit the revision bill during the current ordinary Diet session, aiming for it to be enforced in fiscal 2024.

The outlines say that “phonetic readings generally accepted as names” will be allowed in family registers.

A supplementary document to the outlines also calls for flexible management of the new system, given the historical and cultural reality that there have been some phonetic readings that are used only for names.

However, the government plans not to accept phonetic readings of names “that would confuse society.”

Examples of this restriction include readings with a meaning opposite to the kanji’s meaning, those that are difficult to distinguish from misreadings or misspellings, and those with no relation to the meaning of the kanji….

Discriminatory and obscene phonetic readings of names will not be accepted. Nor will names of characters from comics, anime and other fictitious works that would cause discomfort if used as the names of real people.

As current family registers do not have a section to indicate phonetic readings of names, people listed in Japanese family registers do not officially have phonetic reading of names under the Family Register Law.

In contrast, phonetic readings are written on resident registers. However, according to the ministry, those phonetics readings are not legally official but exist for administrative convenience. Currently, phonetic readings on birth registrations are used for resident registration purposes, but not for family registers.

After the law revision goes into force, kana characters for phonetic readings in birth registrations of newborns will also be used in family registers. Those who already have family registers can submit phonetic reading of their names to municipalities within one year after the revised law goes into force.

In particular, people with concerns such as the frequent mispronunciation of their names by others may find it necessary to have their resident registers revised to include the desired phonetic readings of their names. However, as changing the submitted names will require permission from a family court, the ministry urges careful consideration in deciding the name readings to be submitted.

For those who do not submit phonetic readings of names within one year after the enforcement of the revision, the official phonetic reading will be decided based on readings indicated in resident registers after municipal mayors send notifications to their respective residents.

I’m still wondering about the “cause discomfort” part. Discomfort to whom? How?

- Pronunciation of Japanese Personal Names to be Regulated by Planned Law Revision, Japan News (from the Yomiuri Shimbun), February 18, 2023.

- ‘Pikachu’ could be acceptable reading of name ahead of Japan law change, Mainichi, May 18, 2022.

- Issue of how to read names in kanji requires a full public airing, Asahi Shimbun editorial, February 4, 2023.