Another back issue of Sino-Platonic Papers has been released: The Four Languages of “Mandarin”, by Robert M. Sanders of the University of Hawaii.

Here’s how it begins:

Many hours have been spent at scholarly meetings and many pages of academic writing have been expended discussing what is to be considered acceptable Mandarin. Very often these discussions degenerate into simplistic and narrow-minded statements such as “That’s not the way we say it in …!” or “We had better ask someone from Peking.” Objectively speaking, these disagreements on style reflect a less-than-rigorous definition of which type of Mandarin each party is referring to. Because there has been a failure by all concerned to define fully the linguistic and socio-linguistic parameters of their assumed language(s), Mandarin oranges are often unwittingly being compared with Mandarin apples. This paper is a preliminary attempt to articulate the fundamental differences distinguishing four major language types subsumed under the single English heading ‘Mandarin’. Though the Chinese terms putonghua/guoyu, guanhua, and difanghua help to accentuate the conceptual distinctions distinguishing our four types of Mandarin, it is arguable that even Chinese scholars are not immune from confusing one language with another.

Sanders goes on to indentify and discuss what he calls

- Idealized Mandarin

- Imperial Mandarin

- Geographical Mandarin

- Local Mandarin

The entire text is now online for free in both HTML and PDF (875 KB) formats.

Professor Sanders is also one of the associate editors of the excellent ABC Chinese-English Comprehensive Dictionary.

The

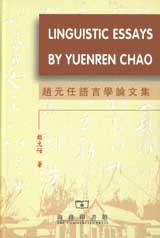

The  Note how the cover of Linguistic Essays, a book printed just last year in China, uses “Yuenren Chao,” the traditional spelling and Western order of his name, rather than “Zhao Yuanren,” the spelling used in Hanyu Pinyin. Also note how the Mandarin title is given in traditional, not simplified, characters: 趙元任語言學論文集, not 赵元任语言学论文集. A nice surprise, on both counts. On the other hand, the botched romanization on the cover of the Mandarin-language collection, which gives “ZHAOYUANREN YUYANXUELUNWENJI” instead of “

Note how the cover of Linguistic Essays, a book printed just last year in China, uses “Yuenren Chao,” the traditional spelling and Western order of his name, rather than “Zhao Yuanren,” the spelling used in Hanyu Pinyin. Also note how the Mandarin title is given in traditional, not simplified, characters: 趙元任語言學論文集, not 赵元任语言学论文集. A nice surprise, on both counts. On the other hand, the botched romanization on the cover of the Mandarin-language collection, which gives “ZHAOYUANREN YUYANXUELUNWENJI” instead of “