芝麻 vs. ZHIMA

The Mandarin word for “sesame” is zhīma (written “芝麻” in Chinese characters). That’s all the Mandarin anyone will need to know for this post. But if any of you non-Mandarin speakers are curious, an approximate pronunciation would be the je in jerk + ma (with the a as in father).

OK, let’s get into it now.

Everyone knows open sesame from the story of Ali Baba and the forty thieves, thought Jack Ma, when he was deciding upon a name for his new company. Alibaba Group Holding Limited is now one of China’s and indeed one of the world’s largest companies. So it’s no surprise that “open sesame” and just plain ol’ “sesame” are still very much associated with the company. And yet the company was acting as if this were not so, at least when it comes to Pinyin.

The U.S. Patent and Trademark Office’s Trademark Trial and Appeal Board recently ruled finally against a trademark application by Advanced New Technologies Co. (hereafter “Applicant”), which was acting on behalf of Alibaba. The mark applied for was “ZHIMA” (as such). The application (serial no. 86832288) was originally filed on November 25, 2015; Applicant requested reconsideration after earlier rejections.

The trademark office has a longstanding rule that trademark applications must, “if the mark includes non-English wording,” include “an English translation of that wording.” But Alibaba didn’t want to do that. The U.S. trademark board ruling lists some of the claims put forth by those arguing for Alibaba.

Applicant refused to submit the required statement for the following reasons:

- There are no Chinese characters (or other non-Latin characters) in Applicant’s Mark;

- A purported meaning of Chinese characters (or any nonLatin characters of even designs or stylizations) cannot be attached to a mark that does not contain such characters);

- Even if similar lettering is used as a transliteration of Chinese characters, Applicant’s Mark, ZHIMA – the only wording at issue – is not a transliteration of Chinese characters;

- Applicant’s Mark ZHIMA is not a translation of Chinese characters;

- Applicant’s Mark does not mean “sesame” in English;

- There is no logical or acceptable reason to ascribe the meaning of any Chinese characters to Applicant’s Mark. Applicant’s Latin-character Mark is a coined word with no translation in a foreign language or meaning which can be attributed.

Applicant concludes that ZHIMA is a coined term, not a foreign word; therefore, a translation/transliteration statement is not necessary.

Although I’m not a lawyer, I do know a thing or two about Pinyin, Chinese characters, and the difference between languages (e.g., Mandarin, English, Swahili, Hebrew) and scripts (the means of writing those languages, e.g., Chinese characters, the Roman alphabet, the Hebrew alphabet). So I feel confident in stating that Alibaba’s claims were risible.

The ruling also quotes the Applicant as claiming that “it is the Chinese characters which translate to ‘sesame’ and that ‘zhima’ is merely a transliteration/pronunciation of these Chinese characters.”

The ruling sums that up as follows: “In other words, according to Applicant the Chinese characters 芝麻 pronounced ZHIMA mean ‘sesame,’ but ‘Zhima’ itself has no meaning.” Elsewhere in the ruling there is this:

Applicant argues, in essence, that while the Chinese characters pronounced ZHIMA means “sesame,” ZHIMA, in and of itself, has no meaning. This is because “the Latin characters ‘zhima’ or ‘zhi ma’ merely represent the transliteration/sounds of particular Chinese characters that are not part of the mark as filed” (i.e., ZHIMA). Without the Chinese characters, ZHIMA has no meaning.

I believe most people would have no trouble laughing at the claim that zhima (the way to write in Pinyin the Mandarin word for sesame) has “no meaning” but is merely something coined by the company. Would anyone believe that this was just some sort of coincidence?

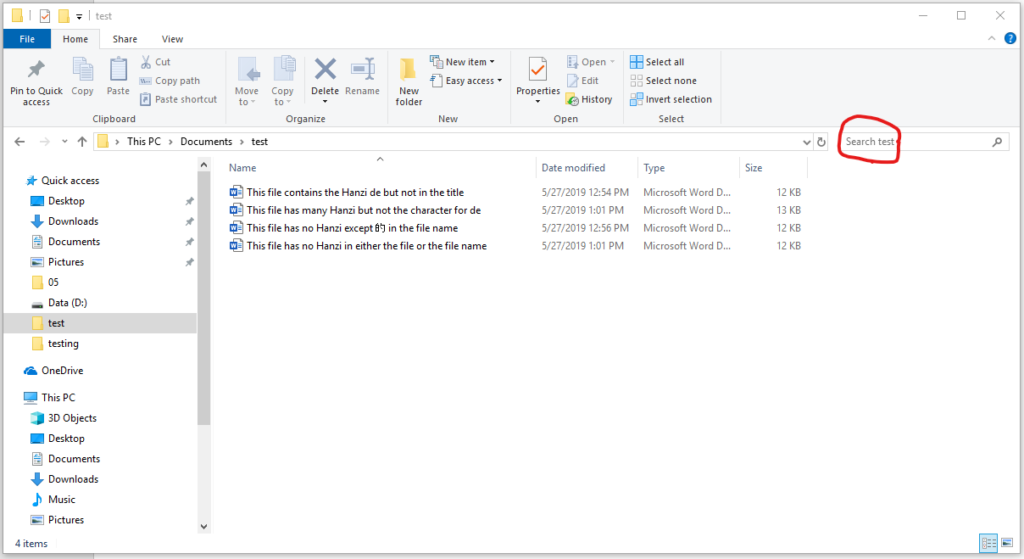

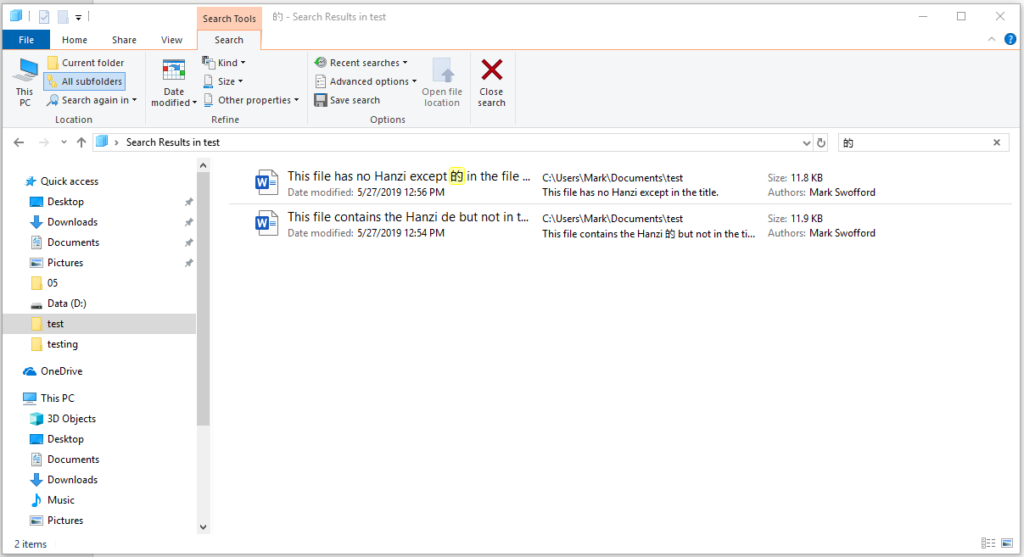

The authorities at the Patent and Trademark Office of course had no trouble finding plenty of examples of zhima being used as such to write the Mandarin word for sesame, including by Alibaba itself. And so the application for a U.S. trademark on “ZHIMA” as a coined word that was supposedly not Mandarin at all but merely something without meaning was rejected once and for all. Importantly, this decision sets a precedent, which should help stop such claims in the future.

Although I’m pleased that the correct decision was reached, I don’t think the decision was necessarily a foregone conclusion, however obviously absurd the claims of Alibaba were. The problem is that a lot of people — including many who really should know better — actually believe nonsense like Chinese characters are necessary to convey the meaning of Mandarin words. The truth is that Mandarin is a language, and Chinese characters and Hanyu Pinyin are scripts (means for writing that language). Chinese characters are not some sort of über language. And, by extension, no matter how many times such claims are repeated, even in what would normally be considered reputable sources, there is no such thing as an “ideographic language” or a “logographic language.”

Speech is primary, not secondary, to the existence of a living language. If by some sort of quirk in the universe every single Chinese character vanished from the face of the Earth, Mandarin would still exist, hundreds of millions of people would still be speaking it with one another, and the Mandarin word for sesame would still be zhima, regardless of how one might write it or what the lawyers for a huge company claim.

Further reading: “Open Sesame” Without Translation Won’t Open Door to Trademark Registration, Lexicology, February 2, 2023