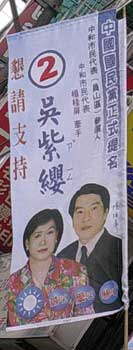

I’ve already written some about campaign banners and literacy. But it’s campaign season again in Taiwan, with elections for neighborhood chiefs to be held this Saturday, and Taffy of Taiwanease.com and Tailingua has sent me a photo of a campaign banner that features zhuyin fuhao (also known as bopo mofo) alongside the characters for the candidate’s given name. That’s the sort of thing I can’t resist.

I’ve already written some about campaign banners and literacy. But it’s campaign season again in Taiwan, with elections for neighborhood chiefs to be held this Saturday, and Taffy of Taiwanease.com and Tailingua has sent me a photo of a campaign banner that features zhuyin fuhao (also known as bopo mofo) alongside the characters for the candidate’s given name. That’s the sort of thing I can’t resist.

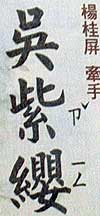

The banner is interesting not only in that it gives zhuyin but also that it gives zhuyin for just some of the characters. For the name Wú Zǐ-yīng (吳紫纓) we are given:

吳

紫 ㄗˇ

纓 ㄧㄥ

(See detail at top right.)

That zhuyin is not used for all of the characters in the name indicates that those who created the banner regarded the zhuyin as advisable for two of the characters. Yet the only character here that is particularly uncommon is the last one: 纓. It is used for yīngzi (纓子), a word for “tassel.”

吳, used for the family name Wu, is a fairly common character and is not displayed with zhuyin.

On the other hand, 紫, which is used for zǐsè (紫色/purple), is roughly the 1,700th most common character. Thus, people of voting age in Taiwan should know this character; yet evidently that cannot be taken for granted. This rank would also mean that people living in China’s countryside, though not in the cities, could be declared “literate” even without being able to read or write this character. (This helps illustrate how standards in China are too low. And, even so, literacy figures there are greatly exaggerated.)

Please permit me to stress the obvious: There is nothing in the least bit obscure in Taiwan or China about the Mandarin word for “purple.” Zǐsè is a word that essentially all native speakers of Mandarin would know, regardless of education, just as essentially all native speakers of English would know the word “purple.” But because the powers that be continue to emphasize the exclusive use of Chinese characters, a sizable number of people are incapable of reading (much less writing) the word for “purple.” This extends even to thousands of other words within people’s vocabularies, a situation that would not exist if romanization were permitted as an orthography.

(I’m still wondering why no bloggers who focus more on Taiwan politics have picked up on what I wrote about before: Ballots in Taiwan do not identify a candidate’s political party in any way (not even a logo), except for presidential elections, which are the one election in which everyone already knows for sure the party affiliation of the major candidates. Am I the only person who thinks this is significant? But it’s off-topic for this site, so I’ll not pursue this further here.)

Oh, if anyone’s curious, the title of the Alice Walker book The Color Purple is translated in Taiwan as Zǐsè zǐ-mèihuā (紫色姊妹花).

Today, I asked 16 different 3rd graders if they could recognize ?, and every single one got it right. I’m sure some 3rd graders wouldn’t know it, but I’d be amazed if I ever met anyone who made it through middle school and couldn’t read that character. Have you considered that there may be aesthetic considerations behind adding zhuyin for two characters instead of just one?

Also, what exactly are you suggesting? Are hoping to replace the Chinese writing system with a romanization scheme as MacArthur tried to do in Japan, after the war?

Hmm, not sure about these ‘aesthetic considerations’. There are other campaign posters (for other candidates) which just have one character annotated, and if the aim was for it to look nice – why not put zhuyin fuhao by all of the characters (including ?)? I suspect that in this case some of the older voting population (in mainlander-dominated Zhonghe where this photo was taken) may not be able to read too well and this KMT candidate wants to ensure that everyone knows her name.

The debate about pinyin replacing written Chinese is probably one for another arena – want to start a Forumosa thread about it? I would be in favour of a gradual replacement, by the way, but then I’m probably in the minority.

Hi, Mark:

I’m inclined to believe, along with Taffy, that if those designing the banner wanted balance, it would be either all zhuyin or none, so the addition is only for those characters where it was thought necessary. I applaud the designers for using zhuyin rather than relying merely on candidate numbers, as so many do.

As for what I am suggesting:

First, literacy in Taiwan is exaggerated. It is not just a matter of knowing a character while in school and being tested again and again, but also retaining it throughout one’s lifetime. And by retention, both reading and writing must play be included. And now, because of computer input, fewer and fewer people are able to remember how to write Chinese characters on their own.

Because of the difficulty of Chinese characters, one can be regarded as literate and still not be able to read or write many words from one’s vocabulary. (Indeed, even those with doctorates in Chinese literature wouldn’t be able to do so.) This is not just a question of simple words like “purple” but also less common but still well-known words such as “tassel.”

This is not a situation that would exist if romanization were used as an alternate orthography. (With Chinese characters and Pinyin used in the spheres in which they work best, this would be a policy of digraphia, or, as Mao Dun labeled it, “walking on two legs.”) The insistence upon the exclusive use of Chinese characters as a standard orthography requires Taiwan (and China much more so) to pay a price in reduced literacy, in increased time spent on studying characters instead of studying writing itself or other subjects, and in other ways.

Within the next two months I’ll be posting a major paper on digraphia.

As for the situation in post-war Japan, it was not as you have probably heard. The definitive book on this is Literacy and Script Reform in Occupation Japan: Reading Between the Lines, by J. Marshall Unger.

As the author neatly summarizes:

The story we are used to hearing is one of ignorant Americans coming within a hair’s breadth of destroying Japanese civilization by forcing their helpless subjects to abandon their centuries-old writing system in favor of the alphabet. However, this tale makes no sense when appended to the true history of the script reform issue up to 1945. A more plausible description of what happened, as demonstrated in this book, is that the loss of the war upset a balance of power among factions competing with one another on the script reform issue. It thereby opened a window of opportunity for romanization that conservative Japanese and Americans, working in concert, shut as quickly as possible.

I strongly recommend this book. A substantial excerpt is available on this site.

Annotating just ? would be the most efficient use of space (if that’s a consideration at all), but annotating the last two characters would have the advantage of marking them as a unit of personal name and thereby constructing an imagined connection between the “friendly neighborhood candidate” and the “voter next door”. This kind of emphasis might be especially expected of a female candidate.

Going OT here, I think not indicating the candidates’ political affiliation is definitely significant. For me it says something about a legacy of Taiwan’s one-party system under the KMT. I also notice KMT candidates in formerly-rural, now-suburban Taichung are less keen on displaying their party logos. One local candidate ran flyers with the following color scheme: navy blue, bright green, orange, yellow, and red.

I hadn’t noticed the reply above; sorry for the slow response. I would say that many Japanese (and western) scholars would disagree with J. Marshall Unger’s description of the history of the occupation. See this thread for further information.