Here’s a public-domain script font: Promocyja.

Here’s a public-domain script font: Promocyja.

Today’s Pinyin-friendly font is Chispa, by Joan Alegret of La Tipomatica. It’s freeware.

Chonburi, by Cadson Demak, is a Pinyin-friendly font that also covers Thai.

Because of its relatively small size, it could work well on Thai-language Web pages that also include Pinyin. Maybe there aren’t many of those now, but eventually….

It is available through Google Fonts.

Essays 1743 is a public-domain font family that has all of the vowel/diacritic combinations needed for Hanyu Pinyin, though the third-tone marks tend to look a bit stiff relative to everything else. Regardless, I’m a sucker for old-style figures (e.g., examples B and D).

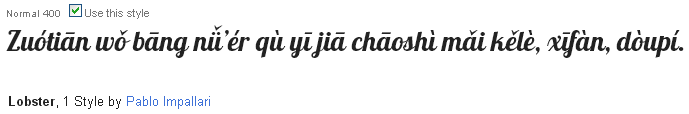

When I first looked at Pablo Impallari’s font Lobster around the end of 2011, it wasn’t yet capable of handling Pinyin with tone marks. But Lobster has improved since then.

A Pinyin-friendly bold condensed script font that looks good and is free — that’s great news.

It’s available through Google Fonts.

Unfortunately, its companion, Lobster Two, doesn’t have the same range and so cannot be used for Hanyu Pinyin with tone marks. But I’ll check again in a few years, just in case.

The encoding problem caused by the hack still isn’t fixed. This means that Chinese characters and Pinyin with tone marks still don’t appear properly on this blog (but they’re fine on pages in the rest of Pinyin.info). But, still, there are some things I’d like to let people know about, including an important announcement coming up soon. So I’m going to start posting some things, even though that means no Hanzi or tonal Pinyin for at least the near future. (Don’t forget: That means Hanzi won’t work in your comments here.) Fortunately, most of the time Pinyin doesn’t really need tone marks.

Without Hanzi and tone marks it’s more difficult to write about Chinese characters and Pinyin, which are, er, only the main topics of the site. But I’ll do what I can. Anyway, why let Victor Mair have all the fun?

So until the encoding issue is resolved y’all can expect a relatively large number of posts catching up on Pinyin-friendly fonts, a few posts covering news and announcements, and probably at least a little of the bile that you’ve come to expect from this site — unless, of course, during the years I’ve let this blog go fallow public signage has all been fixed, the authorities are finally using Pinyin correctly, and people who ought to know better have stopped spouting complete nonsense about Chinese characters. Heh. We’ll see.

The New York Times has just published a profile of Zhou Youguang, who is often called “the father of Pinyin” (though he modestly prefers to stress that others worked with him): A Chinese Voice of Dissent That Took Its Time.

This profile focuses not only on Zhou’s role in the creation of Hanyu Pinyin but also on his political views, which he has become increasingly public with.

About Mao, he said in an interview: “I deny he did any good.” About the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre: “I am sure one day justice will be done.” About popular support for the Communist Party: “The people have no freedom to express themselves, so we cannot know.”

As for fostering creativity in the Communist system, Mr. Zhou had this to say, in a 2010 book of essays: “Inventions are flowers that grow out of the soil of freedom. Innovation and invention don’t grow out of the government’s orders.”

No sooner had the first batch of copies been printed than the book was banned in China.

Although the reporter’s assertion, following the PRC’s official figures, that “China all but stamp[ed] out illiteracy” is well wide of the mark, there is no denying Pinyin’s crucial role in this area. I recommend reading the whole article.

The standard for alphabetically sorting Hanyu Pinyin is given in the ABC dictionary series edited by John DeFrancis and issued by the University of Hawaii Press.

The standard for alphabetically sorting Hanyu Pinyin is given in the ABC dictionary series edited by John DeFrancis and issued by the University of Hawaii Press.

Here’s the basic idea:

The ordering is primarily simply alphabetical. Diacritical marks, punctuation, juncture and capitalization are only taken into account when the strings being compared are otherwise identical. For example, píng’ān sorts before pīnyīn, because pingan sorts before pinyin, because g precedes y alphabetically.

Only when two strings are alphabetically identical is non-alphabetical information taken into account.

The series’ Reader’s Guide presents the specifics of the sort order. Since I don’t have to worry about how much space this takes up on my site, I have reformatted the information slightly to give the examples as numbered lists.

Head entry transcriptions with the same sequence of letters are ordered first strictly by letter sequence regardless of tones, then by initial syllable tone in the sequence 0 1 2 3 4. For entries with the same initial tone, arrangement is by the tone of the second syllable, again in the order 0 1 2 3 4. For example:

shīshi shīshī shīshí shīshǐ shīshì shíshī shíshì shǐshī shìshī Irrespective of tones, entries with the vowel u precede those with ü.

For example:

- lú

- lǔ

- lù

- lǘ

- lǚ

- lǜ

- nù

- nǚ

Entries without apostrophe precede those with apostrophe. For example:

- biàn — argue

- bǐ’àn — the other shore

Lower-case entries precede upper-case entries. For example:

- hòujìn — aftereffect

- Hòu Jìn — Later Jin dynasty

For entries with identical spelling, including tones, arrangement is by order of frequency….

For most users, the most important thing to note is that the neutral tone is regarded as 0, not as 5. Thus, the order is not “ā á ǎ à a,” but “a ā á ǎ à.” And, because lowercase comes before uppercase, not “A a Ā ā Á á Ǎ ǎ À à” but “a A ā Ā á Á ǎ Ǎ à À.”

One can see this in action in the A entries for the ABC English-Chinese, Chinese-English Dictionary. And here are some sample pages from an earlier ABC dictionary.

The ABC series follows the example of the Hanyu Pinyin Cihui (汉语拼音词汇 / 漢語拼音詞彙 / Hànyǔ Pīnyīn Cíhuì) (example), with only one minor difference, as noted by Tom Bishop:

HPC [Hanyu Pinyin Cihui] gave hyphens and spaces the same priority as apostrophes, so that lìgōng sorted before lǐ-gōng, in spite of the tones. Usage of hyphens and spaces in pinyin is still far from being fully standardized. (The same is true in English orthography.) Consequently, for collation it makes sense to give less weight to hyphens and spaces, and more weight to tones, thus sorting lǐ-gōng before lìgōng. In ABC, hyphens and spaces don’t affect the sort order unless they change the pronunciation in the same way that apostrophe would; for example, ¹míng-àn 明暗 and ²míng’àn 冥暗 are treated as homophones, and they sort after mǐngǎn 敏感.