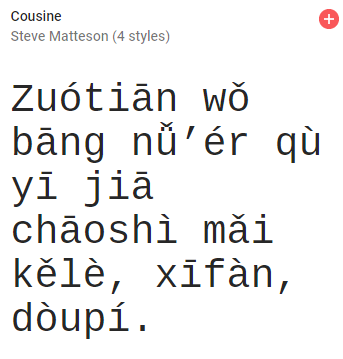

As of January 9, 2018, Google Fonts had 848 font families, 7 of which are monospace faces. Of those, 4 can handle Hanyu Pinyin with tone marks.

Category Archives: Chinese

Pinyin-friendly sans serif faces at Google Fonts

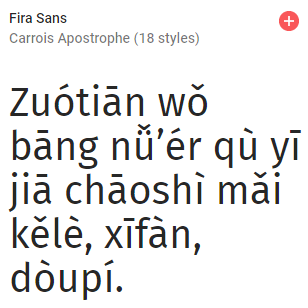

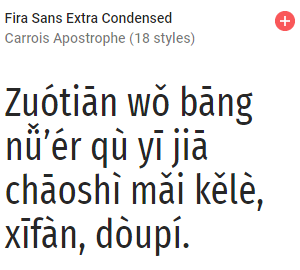

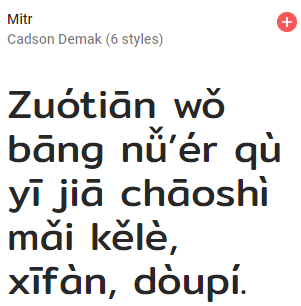

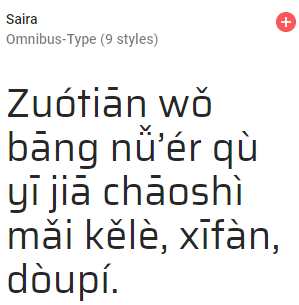

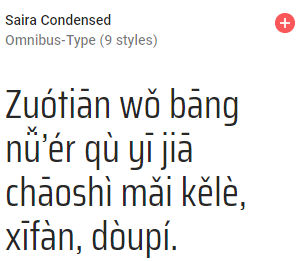

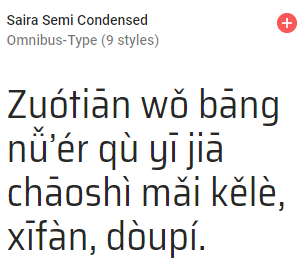

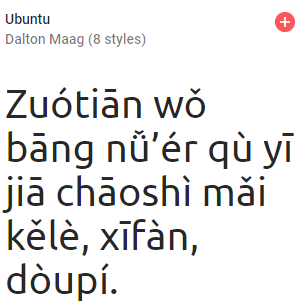

As of January 9, 2018, Google Fonts had 848 font families, 134 of which are sans serif faces. Of those, 22 can handle Hanyu Pinyin with tone marks.

Pinyin-friendly serif faces at Google Fonts

As of January 9, 2018, Google Fonts had 848 font families, 114 of which are serif faces. Of those, the following 22 can handle Hanyu Pinyin with tone marks.

- Alegreya

- Alegreya SC

- Cormorant (Caveat: In the Cormorant fonts, the marks for tones 2-4 are nearly vertical, which may not provide sufficient distinction between them for many readers.)

- Cormorant Garamond

- Cormorant Infant

- Cormorant SC

- Cormorant Unicase

- Cormorant Upright (Caveat: The third-tone mark in ǚ is inverted.)

- David Libre

- EB Garamond

- Faustina

- Gentium Basic

- Gentium Book Basic

- Judson

- Maitree

- Manuale

- Noticia Text

- Noto Serif

- Pridi (Caveat: The mark for second tone and the apostrophe look very similar.)

- Taviraj

- Tinos

- Trirong

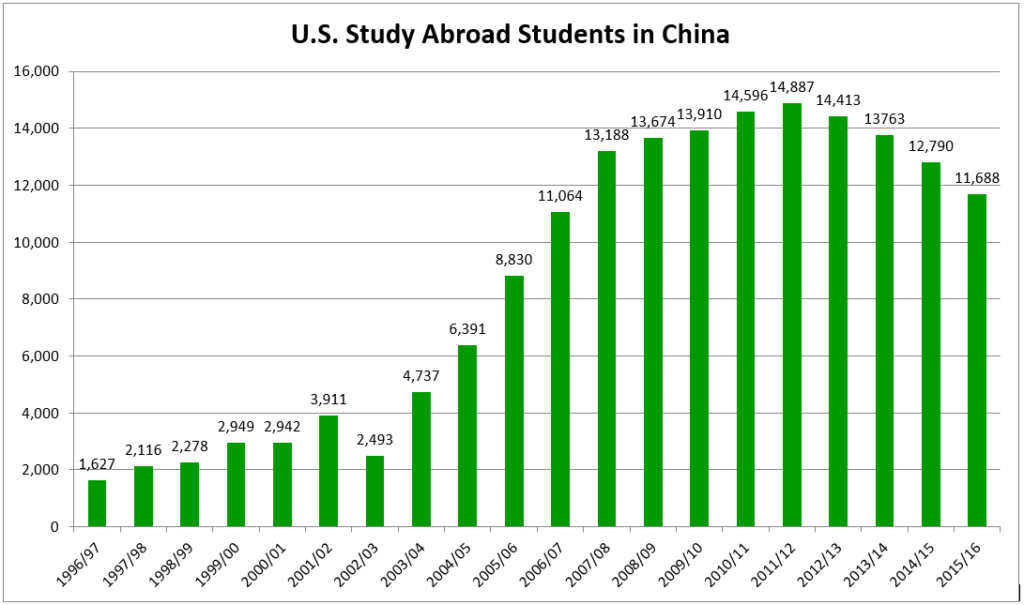

China attracting fewer and fewer U.S. study-abroad students

China is continuing to decline as a destination for U.S. study-abroad students, slipping from fifth place to sixth (behind Britain, Spain, Italy, France, and Germany; with Ireland, Australia, Costa Rica, and Japan completing the top ten).

This likely indicates that the craze for learning Mandarin has already peaked. Greater awareness of the unhealthy levels of pollution in China may also be a factor.

Note: The dip in the 2002–2003 school year was a result of worries about the outbreak of SARS.

Meanwhile, almost all other parts of East Asia saw increases in 2015–2016 over 2014–2015:

| Destination | Students in 2014-15 | Students in 2015-16 | % Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| China | 12,790 | 11,688 | -8.6 |

| Hong Kong | 1,508 | 1,612 | 6.9 |

| Japan | 6,053 | 7,145 | 18.0 |

| Macau | 3 | 4 | 33.3 |

| Mongolia | 71 | 71 | 0.0 |

| South Korea | 3,520 | 3,622 | 2.9 |

| Taiwan | 880 | 980 | 11.4 |

sources:

- Open Doors Fact Sheet: China, Open Doors

- Destinations of U.S. Study Abroad Students, 2014/15 & 2015/16, Open Doors

Additional reading:

- China down slightly as destination for U.S. study abroad students, Pinyin News, October 13, 2015

- China and U.S. study-abroad programs, Pinyin News, January 30, 2012

- China and U.S. study abroad programs, Pinyin News, February 7, 2011

- China and U.S. study abroad programs: update, Pinyin News, January 8, 2010

- China and U.S. study abroad programs, Pinyin News, November 23, 2008

- US students abroad, Pinyin News, Tuesday, November 15, 2005

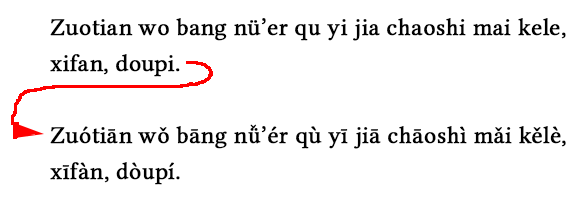

How to add tone marks to Pinyin automatically, sort of

There are plenty of ways to type Hanyu Pinyin with tone marks. These usually involve typing the tone number after the vowel in question or entering a series of special keystrokes to produce the tone mark.

But some consider that too much mafan, or perhaps are unsure of which tones are correct. (Heads up, students learning Mandarin! This post will be useful.) So occasionally I’m asked this question:

Is there a way to type in Hanyu Pinyin and have the correct tone marks appear automatically — even without typing tone numbers or pressing additional keys? Oh, and for free too, please.

The answer is a qualified yes.

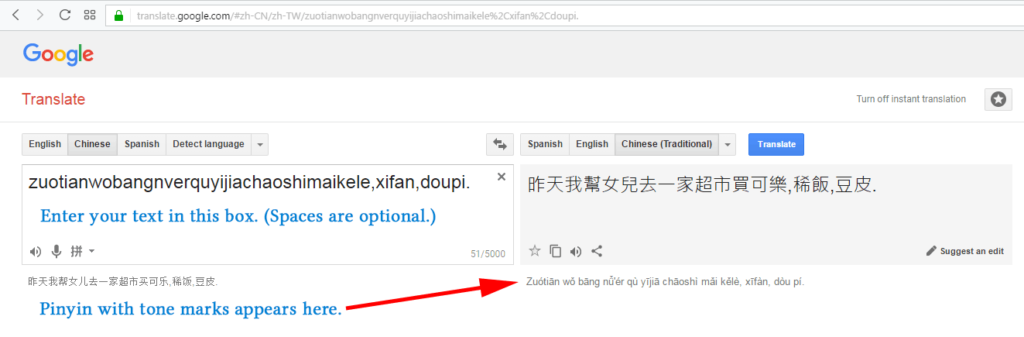

Google Translate’s Pinyin function has come a long way since its inauspicious beginning about eight years ago. For quite some time it has even offered a way to add tone marks automatically, though few people know of this function, which could still use a great deal of improvement.

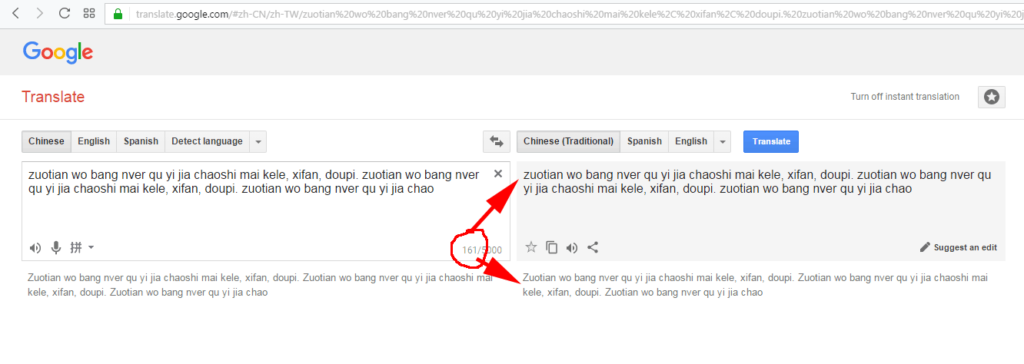

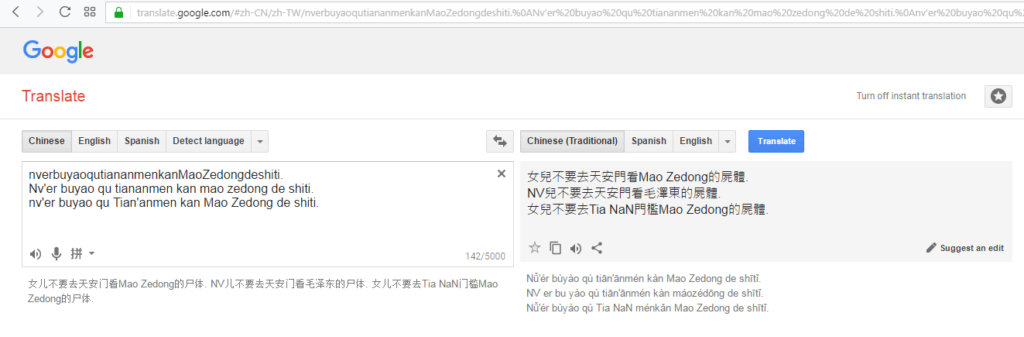

To get Google Translate to produce Pinyin with tone marks as you enter text in toneless Pinyin, first you need to set the system to translate from “Chinese” to “Chinese (Traditional)” or from “Chinese” to “Chinese (Simplified)”.

Enter your text in the box and Pinyin with tone marks will appear below the box on the right.

(Click any image to enlarge it.)

Alas, there are some problems with the system.

A lot of perfectly normal things that are essential to proper writing in Hanyu Pinyin will cause Google Translate to break. So when adding your text, do not use any of the following:

- capital letters

- the letter ü (use “v” instead)

- more than 160 characters (including spaces and punctuation) at a time

Up to 160 characters is fine

But more than 160 characters will break the function that adds tone marks to Pinyin

The following are optional in terms of getting Google Translate to give you good results, though they are not optional in properly written Pinyin:

- apostrophes

- spaces

- punctuation

A second significant problem is that the system doesn’t deal well with proper nouns, failing both word parsing and capitalization, though at least it seems to recognize that proper nouns are units, even if Google Translate doesn’t write them correctly.

So although Google Translate won’t handle everything for you, it can nevertheless be a useful tool for including tone marks in Hanyu Pinyin.

Attitudes in Hong Kong toward Mandarin and Cantonese

About a year and a half ago, when I last posted on a recurring poll of what people in Hong Kong think of Mandarin and Cantonese (as well as other “icons” relevant to Hong Kong) I predicted that “the next survey will show aversion to Mandarin surpassing affection for and pride in that language.”

As of the 2016 survey, aversion to Mandarin was at 17.7 percent of the population, whereas affection for and pride in Putonghua, as the survey labels it, were at 20.1 percent and 17.8 percent, respectively. So I was wrong.

Nevertheless, Mandarin certainly isn’t winning any popularity contests in Hong Kong these days. Although the levels of those averse to Mandarin and those proud of it are now just about equal, among Hong Kongers pride in Mandarin is lower than pride in any other surveyed item. Affection toward Mandarin was similarly lower, avoiding the bottom spot only because the Chinese army came in less than one point lower.

Attitudes in Hong Kong toward Mandarin and Cantonese, 2012-2016

Detail of the above chart, 2012-2016

Generally speaking, positive feelings for Cantonese are higher — usually much higher — than positive feelings for other Hong Kong icons, while negative feelings about Cantonese are much lower than for most other icons. On the other hand, feelings for Mandarin are more highly negative and less strongly positive than for most other icons.

sources and further reading:

- The Identity and National Identification of Hong Kong People, Survey Results (PDF), Centre for Communication and Public Opinion Survey, the Chinese University of Hong Kong

- Attitudes in Hong Kong toward Mandarin and Cantonese, Pinyin News, December 12, 2015

- Xiānggǎngrén de shēnfen yǔ guójiā rèntóng diàochá jiéguǒ (香港人的身份與國家認同調查結果), Centre for Communication and Public Opinion Survey, the Chinese University of Hong Kong, November 2014

- The Identity and National Identification of Hong Kong People: Survey Results, Centre for Communication and Public Opinion Survey, the Chinese University of Hong Kong, November 2014

- Attitudes in Hong Kong toward Mandarin: survey, Pinyin News, December 5, 2011

- Hong Kong’s pride in Putonghua, Pinyin News, December 2, 2006

- Status of Cantonese: a survey-based study, Pinyin News, March 1, 2008

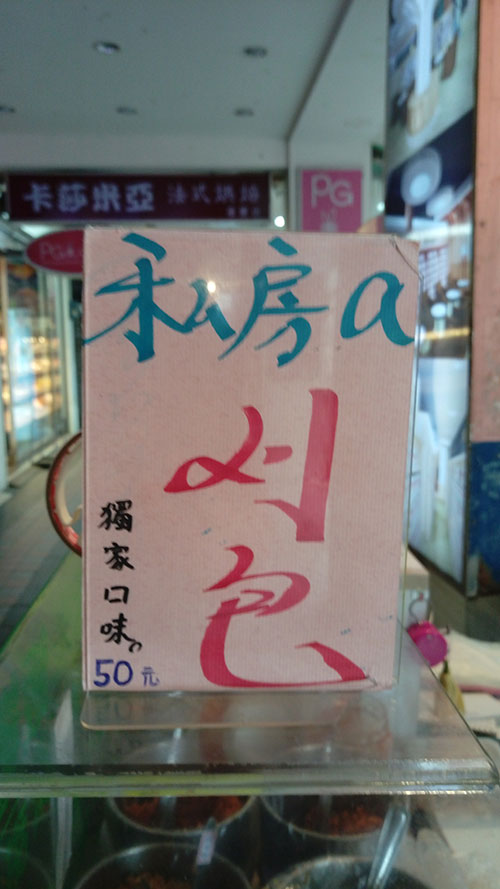

Guabao

Today I’d like to talk about a sign at a stand that sells guabao, a quintessential Taiwanese snack.

I took my own photo, but it didn’t make the guabao look particularly appetizing, so I’m using a public-domain image instead so you can see what one looks like if you don’t already know. But when I buy one I have them leave off the cilantro/xiāngcài. I hate that stuff.

Here’s the sign.

刈包

獨家口味

50元

(NT$50 is about US$1.50.)

The sign uses some Taiwanese, specifically “a刈包.” If the whole thing were in romanized Taiwanese, it would be

koah-pau

To̍k-ka kháu-bī

50 îⁿ

But parts of that are unidiomatic, as Taiwanese expert Michael Cannings informs me. (Alas, my Taiwanese sucks.) So this is a sign in both Taiwanese and Mandarin, which isn’t particularly surprising given that guabao is a Taiwanese food but most people in northern Taiwan use Mandarin most of the time. (I’m using the spelling “guabao” rather than “koah-pau” in most of this post because this is a Pinyin site.)

Something about this sign did surprise me a lot. Can you guess?

- It’s not the use of a Roman letter — I should probably say “English letter” in this case, since here the letter is meant to be pronounced much like the “A” in “ABC” — though regular readers know that’s certainly more than enough to get me interested.

- It’s not that the sign has “刈包” rather than “割包” for guabao. In searches restricted to .tw domains, Google returns 181,000 results for “刈包” and just 41,900 results for “割包”, even though Taiwan’s Ministry of Education prefers the latter form. Even on government Web pages “刈包” beats “割包” by a ratio of more than two to one.

- It’s not the style in which “刈包” is written by hand, though I kinda like that.

- And it’s not even that “a” was used instead of a different Roman letter: “ê”.

What seems to me most distinctive about this sign is that the Roman letter appears in lowercase rather than as “A”.

A single letter being used to represent a Sinitic morpheme in a text otherwise in Chinese characters is almost always written in upper case, e.g., A菜, 宮保G丁, K書. (Oh, that reminds me: I really need to answer that e-mail message about K. Sorry, Steven.)

In other words, if a sign is going to have the Roman letter “a” stand in for the Taiwanese possessive particle (the equivalent of Mandarin’s de/的), I would expect in this particular case for the sign to have “私房A” rather than “私房a”. I’m pleased by the use of lowercase; capital letters should be mainly for proper nouns and the beginnings of sentences.

It’s probably a one-off. But just in case I’ll be on the lookout to see if there’s a trend toward greater use of lowercase.

The text also presents a challenge: How should this be written in Pinyin? The last part (獨家口味 / 50元) is easy, because it’s just straight modern standard Mandarin:

50 yuán

But what to do with this?

刈包

Probably this:

guabao

Most Common Taiwanese Given Names

Below are the most common given names for Taiwanese, as of June 2016. For the numbers of people with any of these given names, see the graph below. Note that there are more Taiwanese with even the tenth-most-popular name for girls than the most popular name for boys.

If you would like a chart of such names for Taiwanese in their twenties and thirties (specifically, those born 1976–1994), see Common Taiwanese given names. For the most common family names in Taiwan, see Taiwan personal names: a frequency list.

For the most likely spelling, bastardized Wade-Giles is given.

Most popular given names for Taiwanese males

| No. | Hanzi | Pinyin | Spelling Likely Used by Someone with This Name |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 家豪 | Jiāháo | Chia-hao |

| 2 | 志明 | Zhìmíng | Chih-ming |

| 3 | 俊傑 | Jùnjié | Chun-chieh |

| 4 | 建宏 | Jiànhóng | Chien-hung |

| 5 | 俊宏 | Jùnhóng | Chun-hung |

| 6 | 志豪 | Zhìháo | Chih-hao |

| 7 | 志偉 | Zhìwěi | Chih-wei |

| 8 | 文雄 | Wénxióng | Wen-hsiung |

| 9 | 金龍 | Jīnlóng | Chin-lung |

| 10 | 志強 | Zhìqiáng | Chih-chiang |

Most popular given names for Taiwanese females

| No. | Hanzi | Pinyin | Spelling Likely Used by Someone with This Name |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 淑芬 | Shūfēn | Shu-fen |

| 2 | 淑惠 | Shūhuì | Shu-hui |

| 3 | 美玲 | Měilíng | Mei-ling |

| 4 | 雅婷 | Yǎtíng | Ya-ting |

| 5 | 美惠 | Měihuì | Mei-hua |

| 6 | 麗華 | Lìhuá | Li-hua |

| 7 | 淑娟 | Shūjuān | Shu-chuan |

| 8 | 淑貞 | Shūzhēn | Shu-chen |

| 9 | 怡君 | Yíjūn | Yi-chun |

| 10 | 淑華 | Shūhuá | Shu-hua |

Note: Although I refer to these as “Taiwanese” names, I give the Mandarin forms (since Hanyu Pinyin is a system for writing Mandarin), not names in Hoklo/Hokkien (the language often referred to as Taiwanese).

Source: ROC Ministry of the Interior.