Recently, Victor Mair posted an image from Taichung of an apostrophe r representing “Mr.” (Alphabetic “Mr.” and “Mrs. / Ms.” in Chinese)

Here’s a companion image for a Ms. Huang.

Recently, Victor Mair posted an image from Taichung of an apostrophe r representing “Mr.” (Alphabetic “Mr.” and “Mrs. / Ms.” in Chinese)

Here’s a companion image for a Ms. Huang.

Xu Xudong (徐旭東/徐旭东), a member of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference and a professor at Central China Normal University in Wuhan, is advocating that public schools in China allocate substantially more time to the teaching of Hanyu Pinyin.

“Gōnglì yòu’éryuán bù jiāo Hànyǔ Pīnyīn, ér xiǎoxué yī-niánjí Hànyǔ Pīnyīn zhī jiāo yī dào yī gè bànyuè, háizi nányǐ gēnshang. Zhè yī wèntí pǔbiàn cúnzài, fǎnyìng qiángliè,” he said.

(“Public kindergartens don’t teach Hanyu Pinyin, and the first grade of primary school teaches Hanyu Pinyin for only one to one and a half months, making it difficult for children to keep up. The problem is widespread and the repercussions are strong.”)

The article does not mention this being in part a class problem, probably because the PRC supposedly does not have such things. But what has been happening is that parents with money tend to send their kids to private preschools where they learn Pinyin and otherwise get a head start on the school curriculum. Or the parents simply teach their youngsters themselves.

Students who don’t get this early boost often fall behind, which is a real problem for something so fundamental. As a result, Xu is proposing that schools spend a semester or even longer teaching Pinyin. The article, which is from a CCP mouthpiece and so should be regarded as representing an official position by at least some influential figures, calls this an easily overlooked but very important issue in basic education.

Intriguingly, Xu also mentions interspersing the teaching of Pinyin with “texts” (kèwén jiàoxué jiāochā jìnxíng / 課文教學交叉進行). The greater use of Pinyin texts in schools — if that’s indeed what is meant — could be a great boon to Pinyin education.

source:

Xú Xùdōng wěiyuán: jiànlì gèng fúhé értóng tèdiǎn de Pīnyīn jiàoxué móshì (徐旭東委員:建立更符合兒童特點的拼音教學模式), People’s Daily, March 5, 2024.

Santa’s in his bus and all’s right with the world.

Although coach buses in Taiwan often use the Gwoyeu Romatzyh romanization system, this bus uses “SAN TA” for “三大”, which is Wade-Giles.

Earlier this week I wrote about San Francisco politicians and what constitutes a Chinese name.

There has been some pushback against the new policy in San Francisco of not letting candidates for office use their own choice of Chinese name unless they can prove they’ve had the name since birth or that the name has been used publicly for at least two years. Those who advocated for the new rule may not have fully anticipated its impact.

“The regulation may unintentionally hurt American-born Chinese candidates who are making their first bids for office,” the San Francisco Standard reported. “Unlike more established politicos who are legacied in, they may not have used their Chinese names publicly, and if they were born in the United States, they also might not have any Chinese-language documents.”

Candidates are quoted as calling the policy “an incredible waste of time” and “absurd.” At least one press conference to protest against the new rule is planned.

Unless the policy is reversed, candidates must provide documentation in support of their self-submitted names before next Thursday.

source: Chinese American Candidates in San Francisco Outraged at Ballot Rule on Chinese Names, San Francisco Standard, December 15, 2023

San Francisco will begin its own enforcement of a 2019 bill that places restrictions on the use of self-submitted Chinese names (i.e., names as written in Chinese characters), requiring that candidates prove they’ve had the names since birth or that the name has been used publicly for at least two years.

All other candidates on the ballot will be assigned transliterated names (i.e., names that use Chinese characters according to rough their having at least rough equivalents in sound in Mandarin, Cantonese, or another Sinitic language).

Since 1999, San Francisco — whose [ethnic] Chinese population is about 21.4 percent of its population as a whole — has required ballots to include the candidates’ English names and their translated or transliterated names in Chinese characters….

[C]andidate for mayor Daniel Lurie, “will likely be assigned a name, 丹尼爾·露里,” which “doesn’t have any meaning. It’s just an approximate pronunciation of his name in English: ‘DAN-knee-er LOO-lee.’”

Lurie had already given himself the name 羅瑞德, which means “auspicious” (瑞) and “virtue” (德), according to the [San Francisco] Standard. The Standard said this name is “widely publicized in the Chinese-speaking world,” but since he is a first-time candidate, if he can’t prove he has used the name for at least two years, it likely will not appear on the ballot in 2024.

Many established local public figures will be grandfathered in, since many will meet the two-year threshold already.

But then there’s this: San Francisco Supervisor Connie Chan, who led the push for the change, said, “Cultural appropriation does not make someone Asian…. There is no alternative definition to whether someone is Asian or not. It should be based solely on a person’s ethnicity and heritage. That’s what this law is about.”

That’s very different than a birth-name or two-year stipulation.

As real as cultural appropriation may be in some situations, wanting to base this “solely on a person’s ethnicity and heritage” seems to me problematic. I doubt Chan would argue that immigrants like herself who gain U.S. citizenship are not real Americans entitled to use Western names like “Connie.”

Then there’s the case of plenty of people whose ethnicity and heritage are not Chinese who live in Asia and have Chinese names, in many cases because they were required by government regulations. I’m one of those people. Although I’m unlikely to ever run for office in San Francisco and I’ve had my “Chinese name” a lot longer than two years, Chan doesn’t seem interested in granting any ground on this issue — at least not from what’s given in the brief quote.

source:

San Francisco targets non-Chinese candidates using Chinese names on ballots, The Hill, December 7, 2023

further reading:

SF politicians and Chinese names, Pinyin News, May 12, 2023

Recent years have been difficult for postsecondary foreign language programs in the United States, with enrollments down 16.6% overall between fall 2016 and fall 2021. Anecdotal evidence points to even steeper declines since then.

This post provides a look at the some of the numbers from the most recent report by the Modern Language Association, focusing especially on the case of Chinese/Mandarin, with some other languages (esp. Japanese) tossed in by way of comparison.

Among the fifteen most commonly taught languages other than English, only three — Korean, American Sign Language, and Biblical Hebrew — showed gains, at 38.3%, 9.1%, and 0.8%, respectively.

Thus, Mandarin and Japanese are among those in decline. Although in total enrollments Mandarin is now ahead of Italian, and Japanese has moved ahead of German, that’s simply because those two Asian languages didn’t fall as far as those two European ones.

From the MLA report:

Chinese/Mandarin enrollments … showed steep declines…. Chinese/Mandarin enrollments fell 14.3% overall and 23.9% at two-year schools, 12.5% at four-year schools, and 29.5% at the graduate level…. Chinese/Mandarin enrollments have been dropping at two-year institutions since 2009, and at four-year institutions since 2013. Graduate enrollments in Chinese/Mandarin have remained fairly steady for the last twenty years; the drop from 2016 to 2021, from 1,266 to 892, is the first time graduate enrollments in Chinese/Mandarin have fallen below 1,000 since 2002.

From the five uses of “Chinese/Mandarin” in the previous paragraph, longtime readers of Pinyin News will note that the MLA acted upon my earlier recommendation to aggregate those two terms rather than treat them separately. But don’t worry: the MLA report doesn’t give the wordy “Chinese/Mandarin” every time in its report. (Although in general use I prefer “Mandarin,” in this post I often use “Chinese” simply to aid people making Google searches.)

Now for some graphs and tables, some directly from the MLA report, others I made using the MLA’s data.

In one encouraging sign for Mandarin, it had a 3:1 ratio of introductory to advanced undergraduate enrollments, making it one of just five languages that had a 4:1 or better ratio, along with Biblical Hebrew (2:1), Portuguese (3:1), Russian (3:1), and German (4:1). This is important because on average it takes more time for native speakers of English to reach the same level in Mandarin than they might achieve in, say, two years of French.

Also, although the number of enrollments is down for Mandarin, that language beat the reduction trend by having a slight increase in the number of institutions offering it at the graduate level: 54 in 2021, up from 52 in 2009. On the other hand, Chinese enrollments overall were reported by 105 fewer institutions in the survey.

As this table from the MLA report shows, Mandarin programs around the United States have been decreasing, stable, or increasing at about the same rates as programs for other foreign languages — which is to say, mainly decreasing. Japanese, however, is continuing to do well given the recent environment.

The figures are about the same for introductory programs, so I won’t bother to reproduce that table (12b).

sources:

Further reading:

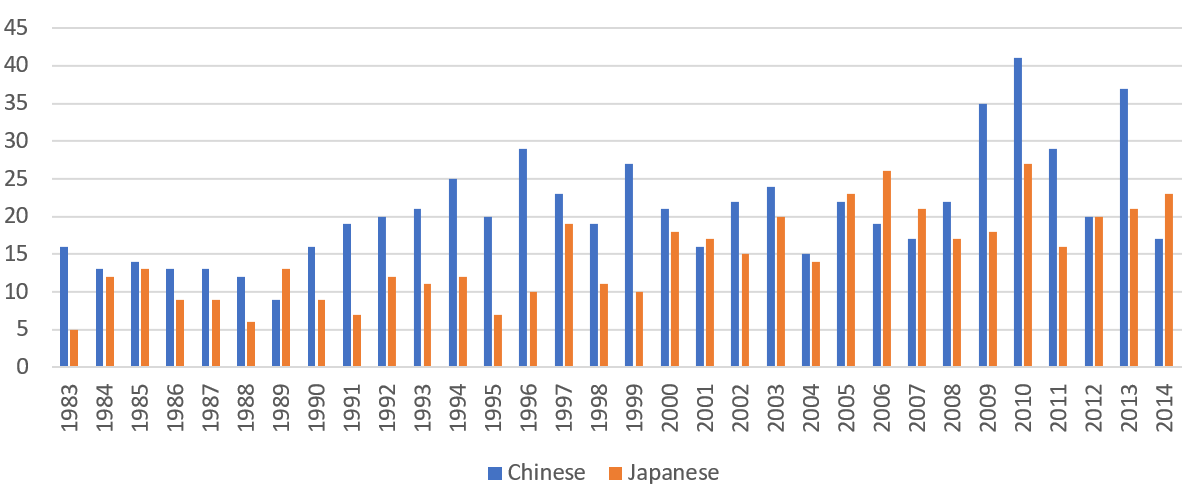

US Doctorates in Chinese and Japanese, 1983-2014

As you can see, in most years more doctorates were awarded in Chinese than in Japanese. The total doctorates over the covered period are 666 for Chinese and 471 for Japanese. By way of comparison, during the same period 870 doctorates were awarded in the United States in Italian.

Interestingly, undergraduate enrollments are typically higher in Japanese than in Mandarin, the reverse of the situation with doctorates.

Although the most recent report on this was issued way back in 2016, recent trends in foreign language enrollments in U.S. postsecondary institutions (to be detailed in a later post) show a steep decline that may well be reflected in the number of people earning doctorates in Mandarin and Japanese in U.S. universities.

source: Report on the Survey of Earned Doctorates, 2013–14, MLA Office of Research, December 2016

further reading:

In March, Taiwan’s Chunghwa Post (Zhōnghuá Yóuzhèng / 中華郵政) issued new postage stamps commemorating Zhuyin Fuhao (註音符號) (aka bopomofo, bopo mofo, or bpmf). The postal service has released another three sheets of these stamps, finishing the series.

sources: