I’ve added another new page to my site: How to find syllable boundaries in Hanyu Pinyin.

After you’ve read it and its companion piece on apostrophes in Hanyu Pinyin, be sure to take the Pinyin syllable-break quiz.

I’ve added another new page to my site: How to find syllable boundaries in Hanyu Pinyin.

After you’ve read it and its companion piece on apostrophes in Hanyu Pinyin, be sure to take the Pinyin syllable-break quiz.

To help answer questions raised by earlier posts, I’ve added a page to my site on apostrophes in Hanyu Pinyin. It begins with the basics.

Here’s all you really need to know about when and where to place apostrophes when writing Mandarin Chinese in Hanyu Pinyin:

Put an apostrophe before any syllable that begins with a, e, or o, unless that syllable comes at the beginning of a word or immediately follows a hyphen or other dash.

Please note there is no “if there is ambiguity” in the rule above.

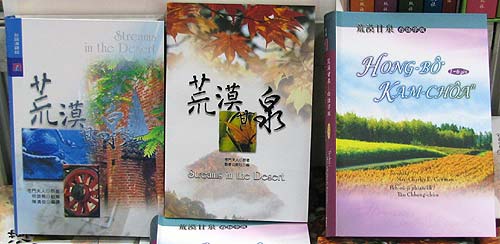

Another discovery at the recent book show was that the Taiwan Church Press has issued three editions of Streams in the Desert: one in a Mandarin translation in Chinese characters, one in a Taiwanese translation in a mixed orthography (mainly Chinese characters, with some romanization), and one in Taiwanese completely in romanization.

Streams in the Desert, a book of devotionals, was written in English by Lettie Cowman, better known as “Mrs. Charles E. Cowman.” Her husband was the founder of the Oriental Missionary Society, which today goes by the name of OMS International. The Cowmans did missionary work in Japan in the early twentieth century.

A representative of the press told me that for every ten copies of the Mandarin version, the company sells two or three of the mixed-script Taiwanese version and one copy of the fully romanized Taiwanese edition.

The fully romanized version sells mainly to people who want to learn Taiwanese rather than those who already speak it, he told me. Its recent publication was an experiment, he added. But I forgot to ask the obvious: Does the press consider the experiment a success?

(from left to right: mixed-script Taiwanese, Mandarin in Chinese characters, and fully romanized Taiwanese)

The birthplace of Lu Zhuangzhang (盧戇章/卢戆章) (1854-1928), a pioneering writing reformer, has recently been identified in Xiamen, China.

Locals said they knew the house was Lu Zhuangzhang’s ancestral home but didn’t know he was famous for his romanization work.

Lu was “the first Chinese to propose a system of spelling for Sinitic languages,” Victor H. Mair notes in his essay Sound and Meaning in the History of Characters: Views of China’s Earliest Script Reformers, which contains additional information about Lu.

Lu was from Fujian and, as a boy, he grew up in Amoy (Xiamen) where romanized writing of the local language was used widely after it was introduced by Christian missionaries. (A romanized Chinese translation of the Bible had already been made in 1852.) At age 21, Lu moved to Singapore where he studied English. After he returned to Amoy four years later, he assisted an English missionary in compiling a Chinese-English dictionary.

Lu’s Yimu liaoran chujie (First Steps in Being Able to Understand at a Glance), published in Amoy in 1892, was the first book written by a Chinese which presented a potentially workable system of spelling for a Sinitic language. His script was based on the Roman alphabet with some modifications. Among other improvements over the sinographs was linking up syllables into words and separating them with spaces. Lu’s system was designed specifically for the Amoy topolect, but he claimed that his system of spelling could also be adapted for the other languages of China. Although he believed that all of the local languages should be written out with phonetic scripts, Lu advocated that the speech of Nanjing be adopted as the standard for the whole nation, as it was when Matteo Ricci had come to China three centuries earlier. Altogether, Lu worked for 40 years to bring an efficient system of spelling to China. He is now viewed by Chinese language workers as the father of script reform.

Local authorities hope to protect the home as a cultural monument.

Tóng’ān fāxiàn Lú Zhuàngzhāng gùjū

Wǒguó “yǔwén xiàndàihuà” de xiānqū, xiàndài Hànyǔ pīnyīn de fāmíng zhě Lú Zhuàngzhāng, qí gùjū jìnrì zài Xiàmén Tóng’ān bèi fāxiàn, wénwù bǎohù zhuānjiā hūyù bǎohù gāi gùjū.

Lú Zhuàngzhāng de gùjū zài Xiàmén Tóng’ān gǔ zhuāng cūn, shì yī zhuàng yǒu bǎi-yú nián lìshǐ de Mǐnnán hóngzhuān gǔ mínjū, Lú Zhuàngzhāng jiù chūshēng zài zhèlǐ.

Cūnmín gàosu jìzhě, tāmen zhīdao zhè shì Lú Zhuàngzhāng jiā de “gǔ cuò”, dànshì bùzhīdào tā shì “yǔwén xiàndàihuà de xiānqū”, yějiù méi rén qù kèyì bǎohù zhè “gǔ cuò”, yīnwèi yīzhí dōu yǒurén jūzhù, hái méi wánquán bèi huǐhuài.

Huòxī Lú Zhuàngzhāng gùjū yīrán bǎocún zài Tóng’ān, Xiàmén Shì wénhuàjú wénwù chù chùzhǎng Chén Zhìmíng biǎoshì, zhēngqǔ ràng Tóng’ān qū wén guǎn bàn jiāng qí dìngwéi qū jí wénwù bǎohù dānwèi.

Jù liǎojiě, Lú Zhuàngzhāng shēngyú Qīngcháo xián fēng sì nián (1854 nián), shì Xiàmén Tóng’ānrén. Zài chuàngzhì pīnyīn fāng’àn, tuīguǎng jīng zhāng guānhuà (jí Pǔtōnghuà), tuīxíng báihuà kǒuyǔ, cǎiyòng héngpái héngxiě, tíchàng xīnshì biāodiǎn, shǐyòng jiǎntǐ súzì děng fāngmiàn, Lú Zhuàngzhāng zài guónèi kāile xiānhé.

source: Tóng’ān fāxiàn Lú Zhuàngzhāng gùjū, Dōngnán Kuàibào, February 15, 2006

At the display for the Taiwan Church Press at the Taipei International Book Exhibition I came across a number of interesting works. The press has issued a 70-volume set of the collected newsletters of the Presbyterian Church of Taiwan. (University and research libraries, take note! So far no sets — NT$150,000 (US$4,600) each — have been sold to America or Europe.) The Presbyterian Church has long been an advocate of the rights of the people of Taiwan to speak Taiwanese without oppression, write in Taiwanese (including in romanization), and enjoy other political and human rights.

The newsletter, which dates back well into the nineteenth century, was written in romanized Taiwanese until 1969, when the KMT forced a change to Mandarin in Chinese characters. While flipping through a volume of the newsletters from the 1920s, I was startled to see that crossword puzzles in Taiwanese were a regular feature. (Click the thumbnail for a larger image.)

It’s one thing to have read of the novels, poems, religious material, and technical manuals written in Taiwanese, it’s another to see something so human and familiar leap out from the page. This really helped bring home for me how much has been lost, especially in terms of opportunities, because of the suppression of romanized Taiwanese, first by the Japanese and then by the KMT.

Interestingly, if you look at the answers below, you’ll see that each of the boxes is meant to be filled in with not an individual letter but with syllabic units.

I’ve tried my hand at creating some crosswords in Mandarin using Hanyu Pinyin, but in individual-letter, not syllabic style. This is a little tricky. In English, all letters of the alphabet can appear at the beginning, in the middle, or at the end of a word. That’s not so in Mandarin as written in Pinyin. The letters i and u, for example, never come at the beginning of a word. And no word ends with anything other than a, e, i, o, u, g, n, or r. (I’ll finish some of those crosswords one of these days, Gus!)

It would be easier to make a crossword puzzle using bastardized Wade-Giles because that has fewer letters but also more finals. But of course not as many people would be interested in solving it, me included.

For even more on the issue of the romanization of Taiwanese, see the Taiwan section of De-Sinification.

Wáng Xuǎn (王选), an important figure in technology related to the printing of Chinese characters with computers, has died at the age of 69.

In 2001 he was awarded the Supreme Scientific and Technological Award, China’s highest award for achievement in the field of science.

sources:

I was amazed and appalled to discover today that a widespread practice for naming abandoned children in China has been to assign the family name after the name of the city of the orphanage. For example, many such children from Guangzhou have been assigned the family name of Guang and those from Shenzhen have been called Shen.

China doesn’t have the same range of surnames of Western countries (more about that some other time), so uncommon names stick out even more there than in the West. Giving children family names like Guang and Shen is not altogether unlike branding their foreheads and ID cards with the word “orphan.”

As if that weren’t bad enough, the given names assigned to children have been largely pro forma as well, with elements of even those often based on geography. Thus, children in the Guangzhou orphanage have often had names of places within the city incorporated into their names, such as “Tian,” “Bai,” and “Li,” with those representing the city’s Tianhe, Baiyun, and Liwan districts, respectively.

Naming someone Li after the Liwan District (荔灣區) is pretty much the same as calling that person “Lychee.”

The non-geographical elements in given names have often been Yong (as in 勇敢, brave), Hong (紅/红, red — often associated with communism), Qiang (強/强, strong), Wen (文, literacy, culture), Ping (as in 浮萍, duckweed), or Cui (翠, emerald green).

Taken as a whole, these names tend to mark children as having been residents of an orphanage and, as my source article states, “are not good for their psychology when they try to interact with the outside world, the orphanage has found.”

No kidding. Just how many decades did it take to figure that out?

Fortunately, the practice has changed, at least in Guangzhou:

Starting this year, Guangzhou’s orphanage has stopped giving its wards the surname “Guang” to prevent them from being identified as orphans.

All children adopted by the orphanage are being given the surname “Li” this year, the Guangzhou-based Southern Metropolis Daily said yesterday. “Wang” will be used next year, followed by other Chinese surnames listed in the “Baijiaxing,” a book of 100 common surnames. Staff members of the orphanage said they would also try to think of unique names for each child, rather than middle names representing the location of orphanage, and a randomly picked given name.

The children can also pick their own name later if they do not like the name given by the institute, the head of the orphanage said.

I wonder how many Westerners who have adopted children from China have innocently continued to use such pro forma names, thinking that they must have been given especially and uniquely to their child.

source: Guang dropped as surname for orphans, Shenzhen Daily, February 13, 2006

Taipei Mayor Ma Ying-jeou, who also serves as chairman of the Kuomintang, recently gave an interview (video) with the BBC’s Mandarin service. He also took questions from callers. One dealt with the issue of romanization.

Ma, who will almost certainly be the KMT’s presidential candidate in 2008 and will likely win if the DPP doesn’t get its act together, again backed Hanyu Pinyin for Taiwan.

I haven’t yet watched the entire piece, which lasts an hour, so I’ll use a newspaper report of this:

Duìyú pīnyīn wèntí, Mǎ Yīngjiǔ biǎoshì, Hànyǔ Pīnyīn suī bù wánměi, dànshì quánshìjiè shǐyònglǜ dá bǎi fēnzhī 80 zhì 90, rúguǒ Táiwān jiānchí Tōngyòng Pīnyīn, wúfǎ yǔ guójì jiēguǐ, zhōngjiāng shòudào shānghài.

(On the question of romanization, Ma said that although Hanyu Pinyin isn’t perfect its international use rate is 80 or 90 percent. If Taiwan persists in using Tongyong Pinyin, Taiwan won’t be able to participate in international links and will finally suffer for it.)

Ma, who also serves as mayor of Taipei, initiated the change of the capital city’s romanization system to Hanyu Pinyin, a move widely applauded by Taiwan’s foreign community.

If anyone watches the whole video, I’d appreciate hearing just when in the broadcast Ma made his remarks on this.

sources: