China has become the fifth most popular destination for U.S. students in study abroad programs, according to the results of a newly released study.

Top 10 destinations for study abroad by U.S. students in the 2006-07 school year

It was only a few years ago that China made it into the top ten for the first time.

Top 10 destinations for study abroad by U.S. students in the 2000-01 school year

The trend evident by comparing the two graphs is also backed up by the numbers: There has been a tremendous increase in the number of American students receiving credit for study abroad.

This latest increase marks a decade of unprecedented growth in the number of American students receiving academic credit for their overseas academic experience, with an increase of close to 150%, from under 100,000 in 1996/97 to nearly a quarter of a million in 2006/07.

Moreover, there has been an increasing interest in non-traditional destinations. In 1996-97, Europe took in 64 percent of U.S. students studying abroad. Although it continues to attract a majority (57 percent) of such students, many other destinations are receiving more students than ever, “fueled in part by an increase in new program opportunities, partnerships between higher education institutions in the United States and abroad, and a range of fields and program durations to accommodate the needs of an increasingly diverse study abroad population.”

Percent of study abroad performed in various parts of the world, 2006-07

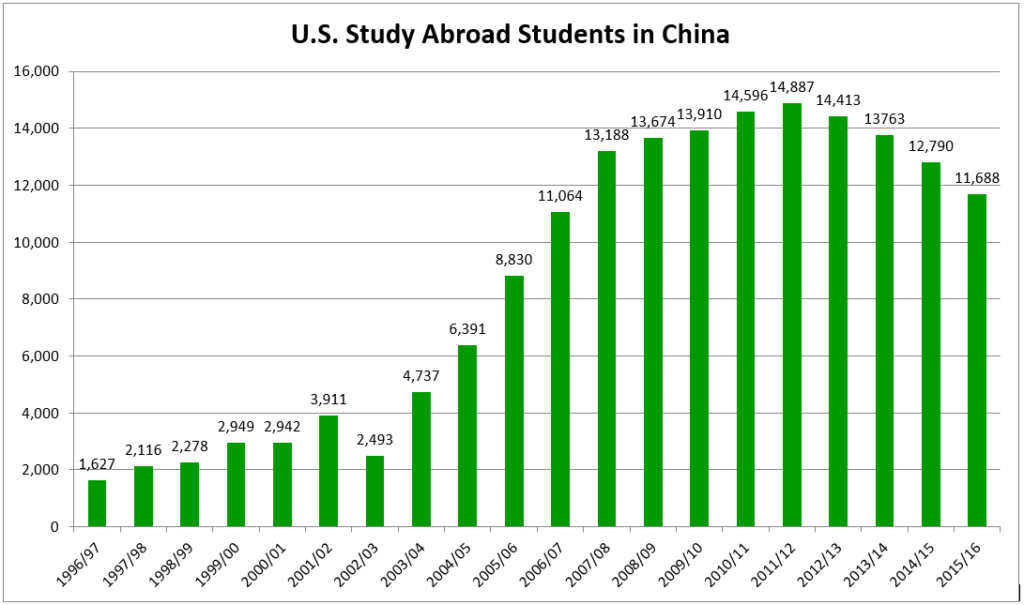

China’s growth as a destination has been strong this decade, other than a dip during the SARS outbreak. Note, however, that China has yet to receive even 5 percent of U.S. study abroad students in any given year, so please don’t misinterpret this post as yet more media hype proclaiming “Everyone’s going to China!” (For the 2006-2007 school year, the figure was 4.6 percent.)

Percent of study abroad performed in select Asian destinations, 1996-2006

The growth of interest in China has helped fuel Asia taking in greater numbers of students. Taiwan has also more than doubled the percentage of U.S. study abroad students it takes in, though the percentage remains so low that this is difficult to see on the graph.

Percent of study abroad performed in Asia, 1996-2006

Note that there’s no indication of just how long people stayed in given destinations. So it’s possible that students spent much more time on average in, say, England than in China — or vice versa.

Here’s the overall breakdown for the time students spent studying abroad:

- 55% in short-term programs (“including summer, January term and any program of 2 to 8 weeks during the academic year”)

- about 36% in semester-long programs

- over 40% in mid-length programs (one semester, one quarter or two quarters)

- less than 5% spend a full academic or calendar year abroad

source: Open Doors 2008: Report on International Educational Exchange

Further reading for students interested in study abroad: IIEPassport Study Abroad Funding.

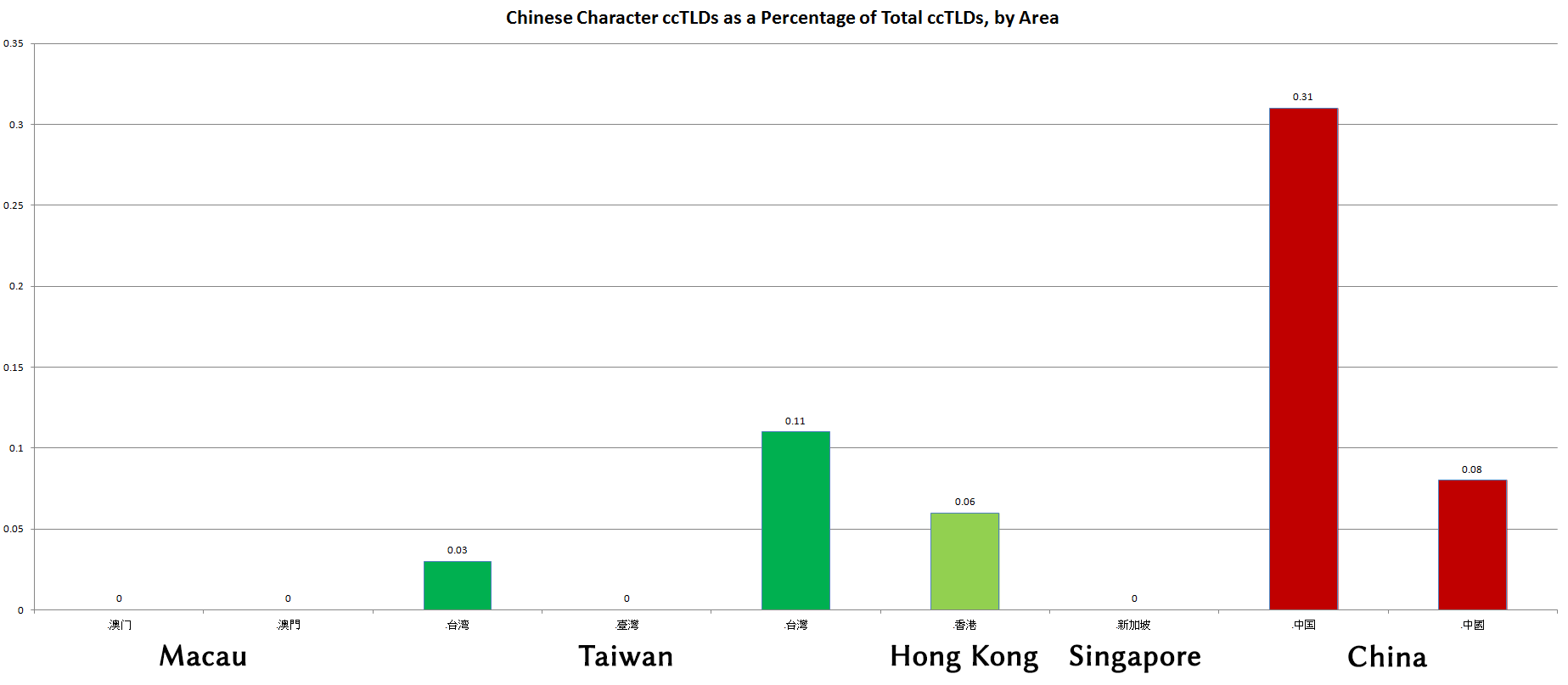

domains compare with the use of .tw domains?

domains compare with the use of .tw domains?  ), so it is omitted here.

), so it is omitted here. and

and  , so those figures are still at zero.

, so those figures are still at zero.  ccTLD, even though the Ma administration, which was in power when Taiwan’s ccTLDs went into effect, officially prefers the more complex form of

ccTLD, even though the Ma administration, which was in power when Taiwan’s ccTLDs went into effect, officially prefers the more complex form of  .

.