Yesterday (January 13, 2018), Google marked the 112th birthday of Zhou Youguang, the father of Hanyu Pinyin, with one of its doodles. (Click the image to see the animated version.)

Google’s description didn’t note Zhou’s remarkable longevity. He lived to see his 111th birthday!

One bit of the description is misleading: “[Hanyu Pinyin] bridged multiple Chinese dialects with its shared designations of sound.” First, what are commonly referred to as “dialects” are actually separate languages (e.g., Cantonese, Hakka, Hoklo). Second, Hanyu Pinyin is designed for modern standard Mandarin, not for other languages, though it could be used as the basis for writing systems for Sinitic languages other than Mandarin; this did not happen on a wide scale, however, because the government of the People’s Republic of China has worked to suppress Sinitic languages other than Mandarin — to say nothing of the languages of Tibetans and other minorities.

A few points are noteworthy about the sketches, specifically the inclusion of Gǔgē, the Mandarin name for Google, written in zhuyin fuhao (a.k.a. bopomofo) (ㄍㄨˇㄍㄜ) and Gwoyeu Romatzyh (guuge) — the doubled vowel indicates third tone.

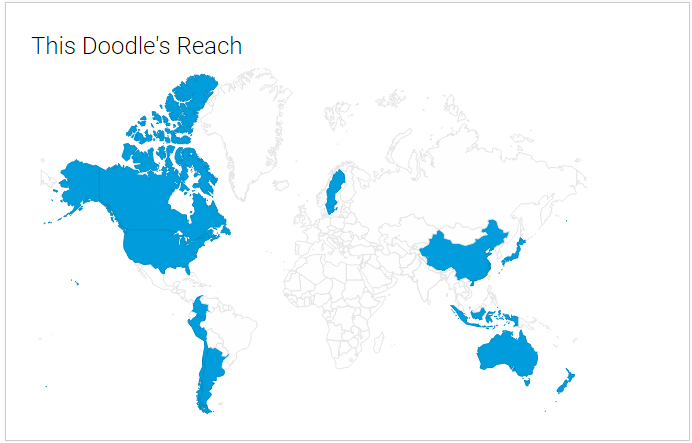

It’s also interesting that the doodle was shown on Google in Japan, China, and Singapore, but not in Taiwan, where Hanyu Pinyin is official but generally used on street signs rather than in personal names.

Thanks to Alex for the tip.

Thanks for this. Disappointed this was not shown in the UK. We got the “African Nations Championship” instead, which bizarrely was only shown in the UK, Ireland, Iceland and just two African countries. They did rather miss the point that yesterday would not only have been Zhou’s 112th birthday, but the first for which he is no longer with us.

if you have pdf chinese pinyin and English book notice me through email

For PDFs of Pinyin texts with at least some English, see

And for a few that aren’t in PDF format, see online texts in Hanyu Pinyin, a few of which have English, including Humpty Dumpty and Dashui Guohuo.

“Second, Hanyu Pinyin is designed for modern standard Mandarin, not for other languages, though it could be used as the basis for writing systems for Sinitic languages other than Mandarin; this did not happen on a wide scale, however, because the government of the People’s Republic of China has worked to suppress Sinitic languages other than Mandarin — to say nothing of the languages of Tibetans and other minorities.”

But this assumes that Hanyu Pinyin is designated as an actual writing system for Mandarin, as opposed to a learning aid that should be discarded by the time a person enters high school, which is how it’s formally treated in the People’s Republic of China. There is only one official writing system for the country: simplified Chinese characters, and it’s assumed to work for all Sinitic languages and dialects, by argument of tradition. Hanyu Pinyin is frequently used for electronic input these days, but the out put is still simplified Chinese characters – you’re not considered literate unless you can read Hanzi.

I don’t see anything inaccurate in what I wrote. We seem to be talking about different issues. Did you perhaps misread my “designed” as “designated”?

As for how Hanyu Pinyin is treated in the PRC, yes, it’s regarded as a set of training wheels. But that doesn’t alter Pinyin’s fundamental nature: It’s a writing system for modern standard Mandarin, however it might primarily be used at present. Similarly, even though many people regard Chinese characters as transcending Sinitic languages (in a way that alphabetic scripts do not), they don’t. DeFrancis demolished that notion long ago in The Chinese Language: Fact and Fantasy.

Then there’s what it means to be considered literate in Mandarin. But that’s a whole ‘nother can of worms. (What does it mean to “read Hanzi”? How many? How is it determined how many Hanzi people can read? What about writing them? What about writing them with a pen and paper, unaided by electronics or dictionaries? How much should we take the PRC’s word for any of this? And so forth.)

I was referring to this sentence: “it could be used as the basis for writing systems for Sinitic languages ***other*** than Mandarin.” Emphasis mine, as I read it as implying that Hanyu Pinyin was already being used – officially or in a widespread sense – as the basis of a writing system for Mandarin, but that doesn’t match my experience, which is that Hanyu Pinyin is only used, in China, as a learning aid and a Romanization standard. Thus, I don’t think the idea of Hanyu Pinyin becoming a writing system for other Sinitic languages is inhibited only by a government’s desire to suppress other languages. Rather, it is also and perhaps more importantly, suppressed by the belief that it isn’t a legitimate writing system for any Chinese language, including Mandarin.

This doesn’t, of course, imply that Hanyu Pinyin isn’t, fundamentally, capable of being a writing system. In fact, all Romanization “standards” for languages can be used as writing systems. But with respect to script adoption, perceptions matter much more than feasibility. I brought up Hanzi not to say that it is fundamentally superior for the task – although I don’t think even DeFrancis would go as far as to say that logographic and alphabetic scripts are equivalent, with respect to “transcending” pronunciation – but that it is perceived to be a legitimate writing system for “Chinese,” in a way that Hanyu Pinyin isn’t.

With respect to literacy in Mandarin – or just Sinitic languages in general – there are competing definitions, but the one definition that seems constant across the world is that one has to be able to read Hanzi, EITHER simplified or traditional. I don’t believe there exists a Sinitic country in which an alphabetic script is considered a legitimate substitute for writing the local language. I find this quite remarkable in contrast to other developing countries, but perhaps not surprising due to the historical identification of Chinese civilization with its script.

Eidolon wrote:

“With respect to literacy in Mandarin – or just Sinitic languages in general – there are competing definitions, but the one definition that seems constant across the world is that one has to be able to read Hanzi, EITHER simplified or traditional.”

No, this isn’t a definition that is “constant across the world.” Consider the case of Dungan, a variety of Central Plains Mandarin:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dungan_language

http://www.omniglot.com/writing/dungan.htm

“Consider the case of Dungan, a variety of Central Plains Mandarin:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dungan_language

http://www.omniglot.com/writing/dungan.htm”

Well, I stand corrected. It seems that certain groups of Sinitic speakers of the Islamic faith have traditionally preferred alphabets – whether Arabic, Latin, or Cyrillic – for writing their variety of Chinese. The practice seems to be associated with religious education and providing better access to Islamic scriptures, which is similar to the role Romanization played for Christian missionaries.

Nonetheless, I’d consider such cases the exception that proves the rule. The Dungan, after all, are an emigrant community that live outside of the so-called Chinese cultural sphere. Within that sphere, in countries dominated by Sinitic speakers, literacy in Sinitic is still determined by characters literacy: this is the cultural belief to which I previously referred as being the main obstacle against Hanyu Pinyin being considered a legitimate alternative for Hanzi, and which supposedly even the PRC language reformers couldn’t ignore when they balanced simplifying Hanzi against creating or adopting an alphabet for writing the national language.