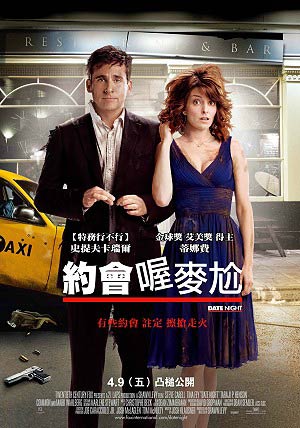

In Taiwan, the new movie Date Night has been given the Mandarin title Yuēhuì o mài gà (約會喔麥尬/约会喔麦尬).

In Taiwan, the new movie Date Night has been given the Mandarin title Yuēhuì o mài gà (約會喔麥尬/约会喔麦尬).

Yuēhuì is simply the word for “date.” The interesting part is “o mài gà” (喔麥尬), which is a Mandarinized form of the English “oh my god.” (I wonder if this, being written in Hanzi despite still being basically English, would pass China’s new need for supposed purity.)

Most people here — especially those younger than about 40 — would simply write “oh my god” (or, less frequently, “o my god”) in English in the middle of an otherwise Mandarin text. (I’ll spare everyone the chart of Google searches; but it backs this up.) But brevity is standard in movie titles here, and “喔麥尬” is a lot more compact on a movie poster than “oh my god.” This, however, raises the question of why “喔麥尬” instead of the equally concise “OMG”. I don’t know the answer to that. But the path of lettered words in Mandarin is certainly not without twists and turns.

Like most other uses of Hanzified English, the results are not entirely faithful to the original sounds.

Mandarin’s ou would be a closer phonetic fit than o for the English “oh”.

There’s Ōu (區/区), a surname. But most of the time this Chinese character is pronounced qū (being one of those many Chinese characters with multiple pronunciations), so that certainly wouldn’t work well. There’s ǒu, which has a more clearly phonetic Hanzi (嘔/呕), but which has to do with vomit (ǒutù/嘔吐/呕吐). Another possible choice would be ōu (歐/欧); but that is associated mainly with Europe and doesn’t get used much as a phonetic component in non-Europe-related loan words outside the word for ohm: ōumǔ (歐姆/欧姆).

Mài (the Mandarin word for wheat), unlike most other Mandarin morphemes pronounced mai (various tones), gets used phonetically in lots of various loan words, such as Màidāngláo (McDonald’s/麥當勞/麦当劳), Màijiā (Mecca/麥加/麦加), Dānmài (Denmark/丹麥/丹麦), and Kāmàilóng (Cameroon/喀麥隆/喀麦隆). So its use is to be expected, though semantically there’s no link. And mài is certainly a better fit for the English my than it is for the Mc of McDonald’s, the Mec of Mecca, the mark of Denmark, or the me of Cameroon.

For ga there’s not a lot of choice. 咖 is often seen in the phonetic loan gālí (curry). The biggest problem here is that the same 咖 is also used as kā in a different, common phonetic loan: kāfēi (coffee). There’s 嘎; but, like 尬, it’s not exactly a well-known character.

Anyway, I could go on for a long time listing various possibilities. But the main point is that Chinese characters just don’t do well at this sort of thing.

As for Pinyin, I suppose the orthography could get interesting: o mài gà, o màigà, omài gà, or omàigà. But a Pinyin orthography would probably simply encourage people to write this in the original: oh my god.

BTW, you may wish to try the following experiment. The gà in o mài gà is most often seen in writing the word gāngà (尷尬/尴尬), which means awkward/embarrassed. Ask native speakers of Mandarin to write gāngà in Hanzi for you by hand without using a dictionary, a computer, or any other form of assistance. I bet that most people — even those with university degrees — won’t be able to write this common, ordinary word correctly.

And for lagniappe, the character 尬 is also sometimes seen in written Taiwanese as the equivalent of Mandarin’s jiā (加/add). I spotted an example of this just the other day on a cafe sign (in the sense of “buy something and ga something else for a special price”) but didn’t have a camera with me.