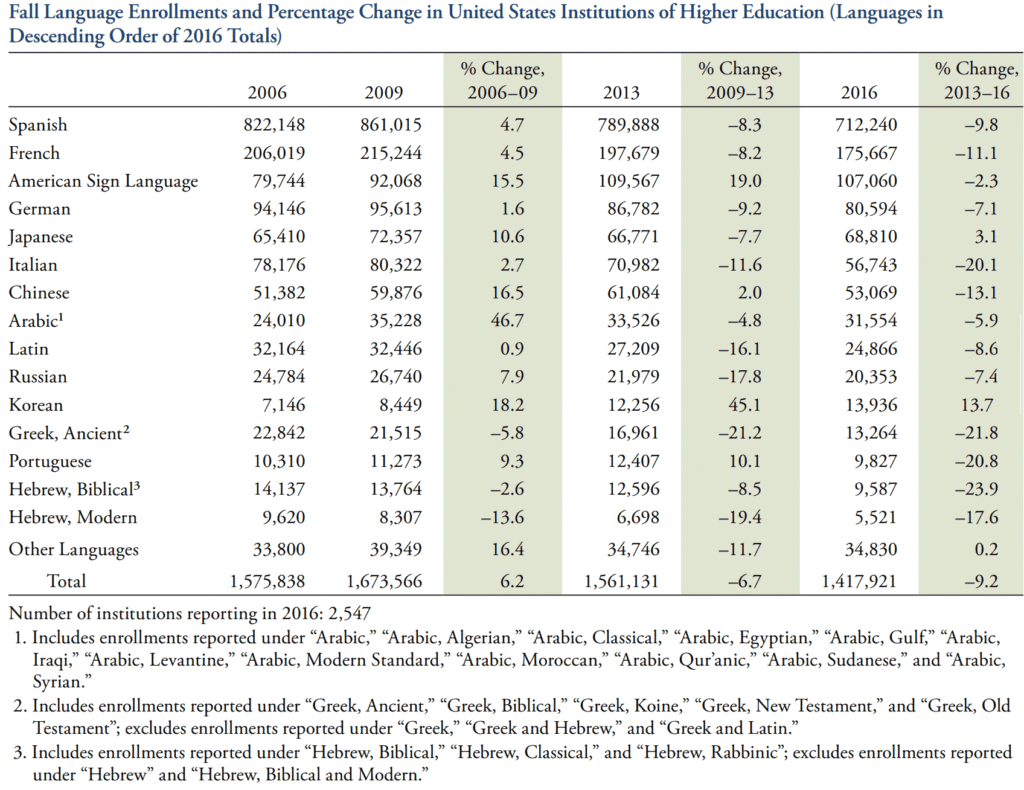

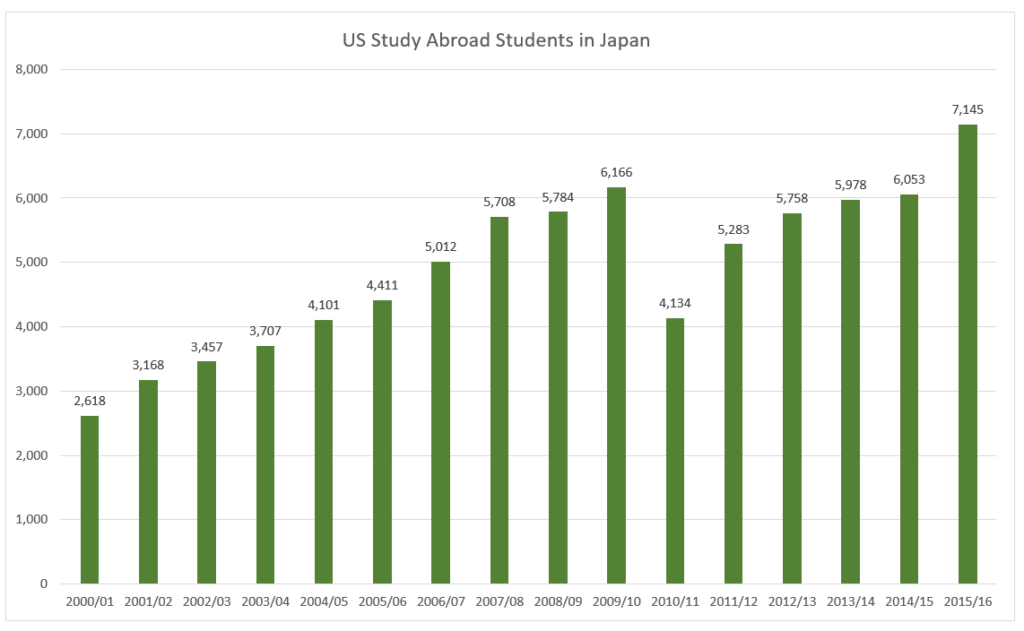

The Modern Language Association recently released its figures for enrollments in languages other than English in U.S. institutions of higher education.

The information that usually receives the most attention is summarized in the report’s Table 1:

Note that the figures for “Chinese” list 61,084 enrollments in the fall of 2013 and 53,069 in the fall of 2016, a decline of 13.1 percent. Those amounts, however, undercount enrollments in a usually small but important way.

As can be seen in the notes to the table above, “Arabic,” “Greek, Ancient,” and “Hebrew, Biblical” represent aggregate numbers — a sensible approach. In the case of “Chinese,” however, only what individual schools label as “Chinese” is summed under that category. The problem is that figures for what is labeled “Mandarin” are excluded. This makes no sense. The language usually labeled “Chinese” is Mandarin. Failure to include Mandarin under “Chinese” is simply wrong.

In Britain, “Chinese” sometimes is used to indicate Cantonese rather than Mandarin. But the figures from the MLA are for the United States.

Seven of the MLA’s reports on language enrollments give figures for Mandarin as separate from “Chinese”:

Separate figures for ‘Mandarin’ and ‘Chinese’ in MLA reports

| YEAR | MANDARIN | CHINESE | PERCENT MISSING FROM ‘CHINESE’ TOTAL |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 1,179 | 53,069 | 2.17 |

| 2016 (summer) | 112 | 5,033 | 2.18 |

| 2013 | 913 | 61,084 | 1.47 |

| 2009 | 1,736 | 59,876 | 2.82 |

| 1974 | 40 | 10,576 | 0.38 |

| 1970 | 88 | 6,115 | 1.42 |

| 1960 | 1,126 | 679 | 62.38 |

As can be seen from the figures above, in most years when figures for both “Mandarin” and “Chinese” are given, the MLA’s figure for “Chinese” is missing least 2 percent of the total. That might not seem like much, but it’s enough to matter, especially to those who wish to compare enrollments across languages accurately. The problem will only grow larger if the word “Mandarin” comes to be used increasingly.

Thus, total enrollments for “Chinese” classes in 2016 were not 53,069 but no less than 54,248; and enrollments in 2013 were not 61,084 but no less than 61,997. That indicates a decline of 14.3 percent, not the 13.1 percent the MLA gives in its table.

The problem is ultimately rooted not in the MLA but in the sloppy use of terms related to Sinitic languages. In part because of this, I believe that schools — indeed everyone — would be better off calling Mandarin “Mandarin” and not “Chinese.” But until that admittedly unlikely adjustment comes to pass, the MLA should be careful to aggregate “Mandarin” and “Chinese” in its tables and figures comparing enrollments across the most popular languages.